Health

Petrol sniffing

Petrol sniffing is a major problem in Aboriginal communities across four Australian states. It destroys health and families. The introduction of a "non-sniffable" petrol variety has greatly reduced, but not ended sniffing. Addicts are now changing to glue, seen by many as even more dangerous.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Statistics on petrol sniffing

Petrol sniffing is a serious problem that has claimed over 100 Aboriginal lives from 1981 to 2003 across Australia [2]. It is very common in Aboriginal communities across the Northern Territory and Western Australia and not restricted to Aboriginal youth.

The practice was first observed in 1951, and is rumoured to have been introduced by US servicemen stationed in the nation's Top End during World War II [1][3].

Of the Aboriginal population in 1994, 4% had tried petrol-sniffing but only 0.3% practised it at that time.

In 2005 there were some 700 petrol sniffers across central Australia [4], with the addiction linked to as many as 60 Aboriginal deaths in the NT between 2000 and 2006, and 121 deaths between 1980 and 1987.

The number of petrol sniffers in the Central Desert region dropped from 500 to fewer than 20 after legislation introduced in 2005 gave police powers to confiscate petrol and take sniffers to a place of safety [5].

The general age range of users is from 10-19 years with a mean of 12-15 years, but use by children younger than 10 is not uncommon.

Petrol sniffing leads to the death of an Aboriginal boy in the movie "Yolngu Boy".

Effects of petrol sniffing

Petrol sniffing produces a variety of short-term effects from pleasurable feelings of excitement, to alcohol-like intoxication, to loss of consciousness. The effects are experienced within a few minutes and only last for a short time (which is the main reason for its use), usually less than an hour.

Short-term effects include euphoria and excitement, feeling light, sensations of numbness, dizziness. These effects may be followed by giddiness, nausea, slurred speech, sneezing, coughing, shortness of breath, indigestion, chest pain, hallucinations, muscle weakness, loss of motor coordination and slowed reflexes.

Long-term use can damage internal organs, the brain and the nervous system because petrol is a solvent. When sniffed, its fumes travel up the nose and dissolve fatty tissue in the brain.

Some damage can be reversed by ceasing use of certain substances, but permanent damage can occur to the brain, liver and kidneys. The person becomes degraded, disabled or dies.

On a larger scale petrol-sniffing devastates not only the sniffer's health but also their families and the wider community by increased domestic violence and family breakdown[6].

Vandalism by sniffers cuts the life expectancy of a teacher's house in Pitjantjatjara lands to less than 2 years.

— Andrew Stojanovski, The Sydney Morning Herald [7]

Story: Two boys die after break-in for petrol sniffing

"Two teenage boys are dead and another is in a critical condition after they were poisoned by petrol fumes inside a fuel container in a remote Aboriginal community.

Four boys from the tiny town of Oenpelli, north of Kakadu National Park, broke into the meat works about 7pm on Saturday night. The boys had reportedly planned to sniff petrol from two quad bikes and a large drum.

Twelve hours after the group gained access through an old air-conditioning unit, a fifth teenager, worried because his friends had failed to respond to his calls, raised the alarm, police said. Using a bolt-cutter, one man opened the metal shipping container to find the four boys unconscious on the floor.

Two, aged 15 and 18, died shortly after they were freed. A 16-year-old is in a critical condition in Royal Darwin Hospital and a 15-year-old was stabilised yesterday." [8]

Ngukurr, a community at the edge of Arnhem Land, asked for eight months for help on chronic petrol sniffing among teenagers. One social worker with expertise in the problem arrived for one day.

— Lindsay Murdoch, The Age [9]

Overcoming petrol sniffing

To reduce petrol sniffing levels in Aboriginal communities a combination of measures is necessary.

South Australia's APY Lands (Anangu, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunyjatjara) reduced the problem by introducing non-sniffable fuel, harsher penalties for trafficking in petrol, extra police and youth workers, a mobile outreach service and more activities for young people [10].

Since the introduction of these measures sniffer numbers have fallen from 222 in 2004 to 38 in 2008 [10]. The number of people sniffing fell 20% in 2005, 60% in 2006 and 46% in 2007.

Youth programs can provide an alternative to substance abuse, but they need to offer an attractive alternative to be effective.

Video: Katherine acts on petrol sniffing

The following video is an ABC news report from the year 2012 when Katherine experienced a spike in petrol sniffing cases.

Introduction of 'non-sniffable' fuel, Opal

In an effort to reduce the epidemic of petrol sniffing in Indigenous communities, BP introduced a new petrol brand, called Opal in early 2005. It contains almost no lead and has only very low levels of the aromatic hydrocarbons ('aromatics'), which give the "high" sought by petrol sniffers.

This is the first time a product has been specifically designed to assist remote communities and in particular Aboriginal communities to fight petrol sniffing.

Prior to the introduction of Opal, Comgas (Avgas rebranded, from Aviation Gas) has been used in the 1990s in many communities to discourage misuse of fuel as an inhalant; however, unlike Opal, Avgas contains lead and was not accepted by communities due to doubts about its suitability.

All petrol stations in Alice Springs now sell the new fuel [11]. Opal fuel is subsidised by the federal government to sell at the same price, costing about AUD 4 million a year.

Note that since 2008 the Australian government does not endorse the use of the term “non-sniffable” as low aromatic fuel is still a fuel product and can be a harmful substance if used incorrectly.

In 2010, 106 Aboriginal communities, roadhouses and other fuel outlets across the states of NT, WA, SA and QLD used Opal fuel [12].

Comparison sniffable vs. non-sniffable fuel

| Property | Opal | Avgas | Unleaded |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colour: | yellow | blue or green | purple/bronze |

| Aromatics: | 5% | 20% | < 48%, typ. 25% |

| Benzene: | 1% | < 3..5% | < 5% |

| Lead: | < 0.005 g/L | < 0.56 g/L | < 0.005 g/L |

| Sulphur: | 150 ppm | 500 ppm | < 500 ppm |

| Sniffable: | no | yes | yes |

Unleaded Opal performs as regular unleaded fuel and can be mixed with other fuel in a petrol tank without affecting the engine.

Success of Opal fuel

Throughout Australia the introduction of non-sniffable Opal fuel helps Indigenous communities to reduce petrol sniffing and improve health significantly.

Petrol sniffing on the lands of the Anangu, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara Aboriginal people (all in South Australia) "has more than halved in just 12 months" [6] with 60% less people sniffing petrol. Compared to 2004 figures the 2006 data shows a huge 80% drop in incidence. A report published in 2014 also found that the number of petrol sniffers plummeted about 80%, from 546 in 2005-07 to 97 in 2011-12 across 15 sample Aboriginal communities [13]. In other communities however it nearly doubled.

With petrol sniffing down, communities could also reduce money spent on policing and health initiatives which amounts to more than AUD 100 million [14].

We estimate that 13 lives have been saved by the introduction of Opal and through community actions.

— Blair McFarland, Central Australian Youth Link Up Service [14]

This could be achieved by a 'no tolerance' attitude of the Aboriginal people in the communities, similar to the 'no grog' attitude many communities have to reduce their alcohol consumption. All communities in Central Australia have now voluntarily switched to the new fuel.

The South Australian government has undertaken the following initiatives to reduce petrol sniffing [6]:

- harsher penalties for trafficking in petrol,

- a mobile outreach service which offers assessment, counselling and education,

- extra police,

- new swimming pools at two communities.

Swimming pools seem to be an interesting approach to provide positive community infrastructure.

Failure of Opal fuel

The introduction of non-sniffable Opal fuel is not all gold. Police reported that sniffable petrol is smuggled into communities where it sells for up to $100 a litre [15].

In April 2007 a boy died after sniffing a bottle of Opal fuel [16], the first known casualty from sniffing Opal fuel [17]. A coronial investigation into the death found that Opal fuel "should not be marketed as a harmless substance". The description as "unsniffable" was "clearly wrong" [18]. Like any volatile substance Opal fuel can be sniffed, and can be fatal when sniffed.

Young Aboriginal people who cannot sniff petrol anymore have been known to switch to other drugs like cannabis, ecstasy and amphetamines [15] or paint. But there's another replacement for sniffable petrol, readily available in every supermarket: glue.

Very much like petrol, glue gives a feeling of euphoria and exhilaration when inhaled. It leads to dizziness, loss of co-ordination, slurred speech and mental deterioration [11]. It is considered, in some ways, more dangerous than petrol. Concern was growing in 2008 in Alice Springs where children were increasingly starting to sniff glue.

Glue and petrol are classified as inhalants, and inhalants can be highly addictive and dangerous to one’s health.

Sniffers have also worked out ways to make Opal fuel addictive. Putting a piece of Styrofoam (for example from a coffee cup) into the fuel causes a chemical reaction which, for bio diesel, lets the foam dissolve "like a snowflake in water" according to scientists [19]. From the resulting mix addicts can get their high [20].

But BP Australia, manufacturer of Opal fuel, says that "Opal fuel can’t be made ‘intoxicating’ by using polystyrene to alter the fuel" [21]. This would only be possible if the added component itself was already intoxicating.

In Arnhem Land, people leave bowls of petrol on car bonnets, in the hope that sniffers will accept the gifts instead of ripping apart fuel lines.

— Andrew Stojanovski, The Sydney Morning Herald [7]

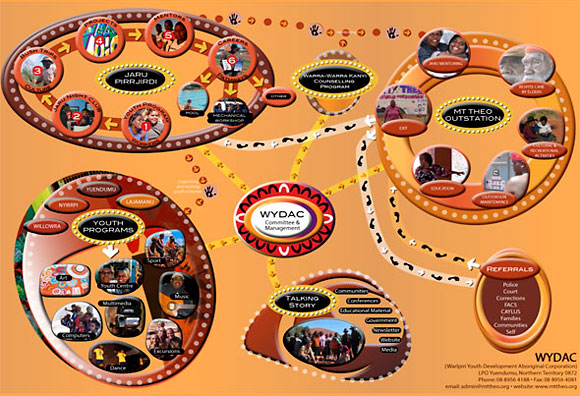

Case study: Mt Theo Program for sniffers

Yuendumu is one of the largest Aboriginal communities in Central Australia, 290 km north-west of Alice Springs. In 1993, the situation in the community was dire as more than half the community's teenagers were sniffing petrol. [22][7] The school's principal reckoned there were more children sniffing in the school grounds at night than attending class during the day.

Sniffers intimidated elders, set car tyres on fire, broke into ceremony camps, broke sacred tribal rules by calling out the name of the dead, pelted classrooms with rocks and encouraged mates and girlfriends. [7]

Aboriginal elder Peggy Nampijinpa Brown and other elders from the community decided to take a zero tolerance approach. Previous initiatives such as banishment, public floggings of sniffers, night patrol and the replacement of petrol with aviation fuel had not stopped the youth from sniffing petrol.

In a last ditch effort Peggy offered to look after all of Yuendumu's petrol sniffers at Mt Theo Outstation, 130 kms north-west of the community, 480 kms from Alice Springs and 50 kms from the nearest main road.

Mt Theo is not only geographically isolated but also a spiritually powerful healing place with strong links to the Dreaming (Jukurrpa in Warlpiri Aboriginal language).

To take the peer pressure out of sniffing, ring leaders or chronic sniffers were removed and sent bush for a month at a time to give "bodies and brains" time away from petrol [7].

The Mt Theo Program started in 1994 and quickly turned into a mammoth task, a task that ultimately would become Peggy's life work.

Warlpiri elders and a dedicated support team looked after the young people and involved them in activities such as hunting, teaching bush skills and going on day trips into the bush, but also leadership development, diversion, respite, rehabilitation and aftercare.

"By the winter of the seventh year, the night air in Yuendumu was different: the smell of petrol was not on the wind," reports Andrew Stojanovski, author of Dog Ear Cafe: How the Mt Theo Program Beat the Curse of Petrol.

Since 1994 the program has extended across the Warlpiri region including many more communities. By 2002 there was no more sniffing in Yuendumu [7]. The success of this program is based on the dedication of the staff and the support of the youth's communities.

The program, formally known as Warlpiri Youth Development Aboriginal Corporation (WYDAC) was created by and for Warlpiri people.

Peggy was presented with the Order of Australia Medal (OAM) in recognition of her invaluable work for the community.

I like the petrol sniffers... we want to make them a little bit strong, healthy ones, give them life.

— Peggy Nampijinpa Brown [22]

Polly Anne Dixon used to be a girl who collapsed on the classroom floor reeking of petrol. After giving up sniffing she won the Triple J's 2003 Heywire competition for her story About life, petrol sniffing and strong voices[7].

Nearly all the funding has been provided by the Warlpiri through mining royalties [7].

Case study: Snuff Out Sniffing (SOS) campaign

"It was pretty bad, some nights he would come home smelling of petrol, he was sniffing glue and petrol, you couldn't reason with him or discipline him, we tried but nothing was getting through," remembers Steven Langton about his 10-year-old son [23]. When Mr Langton himself was ten years old, he himself had started sniffing.

When the Cherbourg community realised they had a serious problem, elders, council, community leaders, government and, importantly, parents got together. They launched the Snuff Out Sniffing program which receives unprecedented support.

Initially no-one in the community wanted to talk about it, even with sniffers visible. But then came the numbers, between 20 and 70, and that some sniffers were as young as seven.

One father told me of putting two of his sons into the shower after they had been out sniffing, drenched in petrol and just bawling because he didn't know what to do.

— Bruce Simpson, SOS campaign member [23]

Once the community was aware of the sniffers they realised that there were no sniffing-specific rehabilitation centres, with most mainly targeting alcohol and other drugs.

That is why the real force of the SOS campaign lies solely in the community, who have gone all out to bring home the zero-tolerance message. "We have community leaders mentoring each other, families who buddy up with other families to support each other through. We've got dads who have been sniffers themselves going into schools to educate the young," reports Mr Simpson [23].

I hope Cherbourg children can see they have people behind them who care about them and support them through this, to stop the sniffing.

— Lillian Gray, Cherbourg Elder [23]