History

Australian 1967 referendum

The 1967 referendum made history: Australians voted overwhelmingly to amend the constitution to include Aboriginal people in the census and allow the Commonwealth to create laws for them.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

What was Australia's 1967 referendum about?

There are common misconceptions about what the 1967 referendum actually changed.

What the referendum was about

1. The 1967 referendum proposed to include Aboriginal people in the census.

2. The 1967 referendum proposed to allow the Commonwealth government to make laws for Aboriginal people.

What the 1967 referendum was not about

The 1967 referendum

- did not give Aboriginal people the right to vote. This right was already introduced in 1962.

- did not grant them citizenship. By the time of the referendum, most of the specific federal and state laws discriminating against Aboriginal people had been repealed. [1]

- was not about equal rights for Aboriginal people. The Constitutional change would not impact at all on laws governing Aboriginal people. However, campaigners hoped that a 'yes' vote would require the Commonwealth government to enact reforms which would eventually achieve better rights for Aboriginal people. [1]

Clever campaigners nonetheless understood to introduce these aspects into their campaigns and use them to favour a 'yes' vote.

Aboriginal elder Gary Williams remembers the referendum

Gary tells what the referendum meant to a 21-year-old Aboriginal youth living in Sydney.

Constitution of the Commonwealth: sections 51, 127

Before Australia became a nation it consisted of separate, sovereign colonies (today's states and territories). For these colonies to form the Commonwealth a Constitution was drafted and each colony had to pass legislation agreeing to become part of the Commonwealth. Then they needed to hold referendums where all electors could have a direct vote on the issue. A 'Yes' majority was achieved at each referendum, which took place between 1898 (South Australia) and 1900 (Western Australia). [2] paving the way for the passing of the Constitution.

Influenced by colonial views of the 19th century, the founding fathers of the Constitution incorporated sections which later ignited discussions which led to the 1967 referendum. These were sections 51 and 127.

Section 51

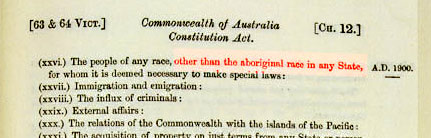

Section 51 of the Constitution covers legislative powers of the parliament. It details for which areas the parliament can make laws, such as trade, taxes, communication, financial and so on, but also people, for example for marriage. As far as people are concerned the Constitution reads:

"51. The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws for the peace, order, and good government of the Commonwealth with respect to:- [...]"

The people of any race, other than the aboriginal race in any State, for whom it is deemed necessary to make special laws.

— Constitution, section 51, clause 26, pre-1967

Section 51 meant that the federal government could make laws for anyone in Australia - except its Aboriginal population. Originally this clause was worded that way to enable parliament to make laws discriminating against racial groups like the Kanakas in Queensland. [3] The words 'other than the aboriginal race in any State' were intended to exempt Aboriginal people from discrimination.

The 1965 prime minister Robert Menzies argued passionately against changing this section and held that if the phrase was removed the parliament could set up "a separate body of industrial, social, criminal and other laws relating exclusively to Aborigines". The inclusion of the words were thought to be "a fundamental safeguard against discriminatory Commonwealth legislation directed against [Aboriginal people]". [4]

But as it stood the Commonwealth also had no power to make laws for the benefit of Aboriginal people.

An important point of referendum supporters was that if the federal government, and not the state governments, make laws for Aboriginal people the laws which varied greatly from state to state [5] would become uniform, and they hoped for the benefit of Aboriginal people.

| Right | NSW | VIC | SA | WA | NT | QLD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voting rights (state) | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Marry freely | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Control own children | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Move freely | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Own property freely | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Receive award wages | Yes | No | No | No | No | No |

| Alcohol allowed | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Source: [5]

Section 127

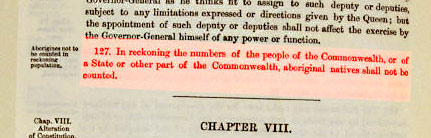

The only other section of the Constitution that refers to Aboriginal people is section 127 which tells about who is to be counted as part of the population of the Commonwealth:

127. In reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth, or of a State or other part of the Commonwealth, aboriginal natives shall not be counted.

— Constitution, section 127, pre-1967

Section 127 meant that when the population of the Commonwealth, of a state or territory is counted, Aboriginal people are not included.

Until well into the early 1960s politicians feared that by counting Indigenous people this would affect the quota that decided the number of seats a state could hold in parliament. Hence the greater the number of Aboriginal people within a state, the greater the number of seats. This, it was argued, would give advantage to states with a great number of Aboriginal people [6] and it was feared that Western Australia and Queensland could lose a seat.

The white Australian population at that time was about 3.7 million; the Aboriginal population can only be estimated to around 50,000 to 60,000. Newspaper sources of the early 1960s considered it "a mildly entertaining historical oddity" [7] trying to count Aboriginal people on one day, and an impossible task to do:

Trailing after the primitive tribesmen for the purposes of enumeration would have been more difficult than rounding up a mob of wild brumbies.

— 'Candid Comment' in the Sydney Morning Herald [6]

Petitions, motions and private bills: referendum initiatives

The referendum that changed the Constitution was held in 1967, but this was just the culmination of events which started more than a decade earlier.

Australia is shocked—petitions

In early 1957 the Grayden Report revealed that malnutrition, blindness and disease were all commonplace among the Aboriginal people of the Warburton Ranges region, [8] about 300km west of the border between Western Australia and South Australia. Australia's shocked white population learned for the first time about the appalling living conditions of Aboriginal people whom they had scarcely heard of before.

Concerned individuals formed action groups, one of which was the Federal Council for Aboriginal Advancement (FCAA) founded in 1958. To achieve equal citizen rights for Aboriginal people the FCAA wanted the Australian Constitution to be changed to enable the Commonwealth government to legislate also for Aboriginal people.

The Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship ran a petition campaign in 1957 about the situation of the Aboriginal people of the Warburton Ranges. A year later the FCAA ran a similar petition which was signed by 25,000 people in three months. [8] Both petitions called for the amendment of section 51 and the repeal of section 127. Both failed.

Initiatives from within the government

In 1962 the Australian Labor Party opposition submitted an urgency motion seeking a referendum to include Aboriginal people in the census. [9] Although the debate mainly focused on the redistribution of electoral seats in the parliament, the opposition also argued that "everything that can reasonably be construed as discrimination should be eliminated from the Constitution."

The motion did not convince the government nor the press who claimed that "the practical reason for section 127 is rapidly disappearing" [7] because in 1962 fewer than 2,000 Aboriginal people still lived undisturbed tribal lives, and the covered message was that they would ultimately disappear entirely.

Constant battle

From 1962 to 1964 more than 50 petitions were submitted to the government, all asking the same change: To change section 51 and to repeal section 127 of the Constitution.

Part of this wave of petitions was due to the work of the FCAA who in 1963 ensured that over a seven-week period every day began with the tabling of petitions. [8] It was a clever move: Instead of submitting one big petition presented only once and then filed, a new petition each day kept the issue alive. The FCAA managed to collect more than 100,000 signatures in favour of a constitutional change.

By 1964 the constant tabling of petitions, the submission of Constitution Alterations Bills and Private Member's Bills seems to have had some effect on politicians' minds. Discussion if section 127 should be repealed or not shifted to when it should happen and the costs of a referendum. [4]

In the second half of 1965 Prime Minister Sir Robert Menzies announced his retirement for 1966.

It took just on 10 years to get the Federal government to agree to hold a referendum and then only after 15 months of petitions being presented in the Parliament on every single sitting day.

— Jack Horner, secretary, Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship [10]

A referendum at last?

On 11 November 1965 it was announced that a referendum would be held on 28 May 1966 seeking approval to increase the number of members in the House of Representatives (to match the growing population) and, among others, to repeal section 127. [11]

No mention of section 52 at this time for the government was still convinced that it protected Aboriginal people rather than discriminated against them.

The previous 12 referendums included 26 proposals, four of which Australian voters agreed with but 26 they rejected. Consequently the Prime Minister must also have feared that if he included too much change, Australians might have rejected the referendum altogether and with it the increase in the House of Representatives.

Liberal backbencher W. C. Wentworth campaigned strongly for the amendment of section 51 of the Constitution. He argued that by enabling the Commonwealth to make laws for the Aboriginal people these would be for their advancement. State laws would not be affected by Commonwealth legislation and states could receive federal funding. [13] Wentworth's bill was later supported by teachers of the Sydney University.

But Wentworth's efforts seemed doomed. A private member's bill Wentworth introduced to government in March 1966 was not put to a vote and subsequently lapsed. [14]

Aboriginal protest in Canberra

In 1965 the FCAA was renamed to Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI) to include Indigenous people from the Torres Strait. It took over responsibility for keeping the constitutional amendment issue politically alive.

On December 1st, 1965 a group of 36 Aboriginal people went to Canberra to protest about clause 26 of section 51. [12] Outside Parliament House they showed placards while they lobbied Members of Parliament inside, including Mr Wentworth.

Among the protesters were famous names like Faith Bandler (FCAATSI NSW State Secretary), former Australian Rules footballer and boxer Charles Perkins and Brisbane poet Kath Walker (later known as Oodgeroo Noonuccal).

After Prime Minister Harold Holt took over power from Robert Menzies in 1966 he decided to postpone the referendum that year. His newly elected government was too occupied with the "many important and pressing matters arising at home and abroad" [15], the former alluding to a general election later that year, the latter to the war in Vietnam. Behind that reasoning was also the fear that if the referendum failed, it would be a blow for the new government.

People in Australia have to register their dogs and cattle, but we don't know how many Aborigines there are.

— Faith Bandler, 1965 [12]

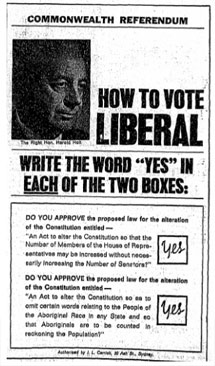

The 1967 referendum goes on its way

On February 23, 1967 the federal cabinet finally decided to hold a referendum in May that year. [16] A few days later Prime Minister Holt announced that the referendum would go further than the previous draft. Now also clause 26 of section 51 should be amended and the words 'other than the aboriginal race in any State' dropped. [14]

This must have come as a great victory of W C Wentworth's long campaign which seemed to have reflected the general public opinion that these words were discriminatory. But while Wentworth had argued for a replacement of these words with a new phrase that would advocate positive laws for the advancement of Aboriginal people, Holt went for a mere deletion.

I would like to see spelt out in the Constitution the Commonwealth's power to help Aborigines and to see a prohibition against adverse racial discrimination towards the Aborigines or anyone else.

— W C Wentworth, Feb 1967 [14]

On March 2nd 1967 Prime Minister Holt introduced legislation for a referendum to be held on May 27, 1967.

In April, FCAATSI organised a deputation to Canberra to seek support for a 'Yes' vote on the Aboriginal question [17]. FCAATSI feared that voters would not understand the effect of a 'yes' or 'no' vote and wanted to check on what politicians had done in their electorates to support a 'yes' vote.

FCAATSI was helped by the heads of churches who also supported a 'yes' vote, distributed how-to-vote cards and tried to explain to voters what it was all about.

What the 1967 referendum meant to Aboriginal people

In an article published shortly before the 1967 referendum, Charles Dixon, Manager of the Foundation for Aboriginal Affairs explained how he as an Aboriginal person felt about the referendum: [19]

- Acceptance as a person. Dixon felt that up until the referendum Aboriginal people had not been seen as "human beings".

- Fear of apathy, ignorance, complicated ballot paper and racial hatred which could cause a 'no' vote. This would mean "bad blood" between black and white for "the foreseeable future".

- It's too late. Dixon thought that it didn't matter "if and when [sections 51 and 127] go" since "it's too late to heal the scars of years of discrimination".

- Special laws for the benefit of Aboriginal people which the government will make.

- A unified law. For too long an Aboriginal person would break the law somewhere purely by moving around as a citizen or to "exist on that very spot", because each state had its own laws governing Aboriginal people.

- More funding. With the Commonwealth in charge of Aboriginal laws, Dixon hoped that funds or trained personnel would help policies work.

- An Aborigines' Bureau staffed by Aboriginal people and looking after Aboriginal affairs.

1967 Referendum

Sailed their boats Up to our shores Aimed their guns And made their laws No man’s land Was what they said Did not want to count One single head As flora and fauna We were seen Did not have a say In our own dreams British subjects Was the term they used? Wasn’t even asked For our important views Alien citizens On our own sand Treated as foreigners By treacherous hands Our rights were shunned Our lives controlled We watched in sadness Saw it all unfold Then came a sound Like a rushing tide Throughout the land It rolled far and wide And one by one The voices all rose In an almighty crescendo We watched them grow A referendum A deciding vote To take count of us Bring healing and hope Set the wheels in motion And opened the door “The Aboriginal question” The changing of laws The scars run deep Within our lives But we will fight on For justice with pride And hope one day soon We will stand hand in hand As we press for equality In our Great Australian Land

Nola Gregory wrote this poem for the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum. Read more Aboriginal poems.

Video: Faith Bandler and Oodgeroo Noonuccal on the referendum

Historical events that influenced the 1967 referendum

- 1957 Test explosions of atomic bombs at Maralinga, South Australia

- 1962 The Commonwealth Electoral Act is amended to give the right to vote to all Aboriginal people.

- 1966 Stockmen and women at Wave Hill walk off in protest against intolerable working conditions and inadequate wages.

- 1966 Charles Perkins leads Freedom Ride by Aboriginal people and students through NSW in support of Aboriginal rights.

The 1967 referendum results

In what is a twist of history Aboriginal people who were entitled to vote in the Northern Territory and Australian Capital Territory were not entitled to vote in a referendum according to the Constitution. This prevented around 3,000 to 4,000 Aboriginal people in the NT from voting for their own cause.

In 1967 it was estimated that between 8,000 and 10,000 Aboriginal people were registered to vote throughout Australia. [21]

For the referendum to pass it was required that the question was supported by a majority of voters in a majority of states, in 1967 that meant about 2.5 million 'yes' votes in four states (the 'territories' were not eligible to vote, i.e. Northern Territory and ACT).

Jack Horner, member of the Aboriginal-Australian Fellowship, remembers the night the votes were counted: "On the night of 27 May 1967, Jean [his wife] and I were in the tally room at Circular Quay, in Sydney, and we couldn't believe it as the results were consecutively dropped onto the calculating machine. Those results exceeded our greatest expectations, and everyone's—it was the triumph of an appeal to the sense of justice." [22]

On 10 August 1967 the act changing the Constitution became law in Australia.

The Constitution of Australia never has, and to-date still does not, protect basic human rights or offer protection against racial discrimination.

Results by state

Referendum question: "Do you approve the proposed law for the alteration of the Constitution entitled 'An Act to alter the Constitution' so as to omit certain words relating to the people of the Aboriginal race in any state so that Aboriginals are to be counted in reckoning the population?"

| State* | Yes | No | Informal | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| votes | % | votes | % | ||

| New South Wales | 1,949,036 | 91.46% | 182,010 | 8.54% | 35,461 |

| Victoria | 1,525,026 | 94.68% | 85,611 | 5.32% | 19,957 |

| Queensland | 748,612 | 89.21% | 85,611 | 10.79% | 9,529 |

| South Australia | 473,440 | 86.26% | 75,383 | 13.74% | 12,021 |

| Western Australia | 319,823 | 80.95% | 75,282 | 19.05% | 10,561 |

| Tasmania | 167,176 | 90.21% | 18,134 | 9.79% | 3,935 |

| Total for Commonwealth | 5,183,113 | 90.77% | 527,007 | 9.23% | 91,464 |

* Residents of the Northern Territory and the Australian Capital Territory did not have the right to vote in referenda at that time. Source: [23] See also SMH Referendum results by state[24]

Referendum notes:

- The heaviest 'no' voting came from country electorates (e.g. 18% in northern NSW).

- It was the biggest 'yes' vote in history on any Commonwealth referendum to-date.

- The previous greatest 'yes' vote was in the 1906 referendum (to enable senate elections for both Houses to be held concurrently).

- In the WA electorate of Kalgoorlie more than 28% of votes opposed the proposal.

- The proposal on Aboriginal people was only the fifth to be carried since Federation.

- The 'no' vote was most dominant in states that had the largest Aboriginal population and have been criticised most for their treatment of Aboriginal people.

- Up to 1967, in 60 years only 5 out of 26 referendum questions have been carried.

My grandfather used to tell me that white Australia had done enough by voting yes in the 1967 referendum. All the evidence points to the contrary.

— 'Reeree' in an SBS discussion forum [25]

1967 referendum resources

The 1967 Referendum: Race, Power and the Australian Constitution explores the legal and political significance of the referendum and the long struggle by black and white Australians for constitutional change. It traces the emergence of a series of powerful narratives about the Australian Constitution and the status of Aboriginal people, revealing how and why the referendum campaign acquired so much significance, and has since become the subject of highly charged myth in contemporary Australia.

Attwood and Markus's text is complemented by personal recollections of the campaign by a range of Aboriginal people, historical documents and photographs.

Movie: Vote Yes for Aborigines, a documentary by Aboriginal woman Frances Peters-Little covering 100-year-plus lead-up to the referendum, questions the referendum's success and explores the social attitudes and influences of those times and since.

'Vote Yes for Aborigines' draws on rarely seen archival footage and attempts to answer the question of what came of the 1967 referendum.

The Australian Broadcasting Corporation prepared a documentary for the 50th anniversary of the 1967 referendum called Right Wrongs. It offers personal stories, opinions and historical recordings of what happened and asks "How far have we come since 1967?" Chapters include life for Aboriginal communities before the vote, finding their voices and standing up for their basic human rights, campaigning and activism leading to the referendum, and what has changed, what has stayed the same, and the legacy of the referendum.

Where the 1967 referendum failed

What was the effect of the 1967 referendum? Did the federal governments act to the expectations of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people who so passionately had fought for the Constitution to be changed?

Sadly this hasn't been the case. The government at the time didn't expect a 'Yes' vote and, two months after the referendum, still had no idea how to use the new powers it had been given. [26] While then-prime minister Harold Holt is said to have had a genuine interest on improving Aboriginal affairs, "all hopes that the referendum would result in positive change drowned with him" [26] when he never returned from a swim in the ocean.

The next government with PM John Gorton was disinterested and not motivated to take action, and it seems this attitude still lingers today. Governments of all political colours continue to 'forget' to consult with Aboriginal people during law-making business.

While the 1967 referendum helped delete discriminatory references specific to Aboriginal people, it put nothing in their place. Torres Strait Islanders, who have a culture very different to mainland Aboriginal people, have never been referred to in the constitution. This constitutional silence is what drives many initiatives calling for constitutional recognition.

That referendum also did not address clauses in the constitution that permit racial discrimination generally. Aboriginal people are often on the receiving end of discrimination and like to see these clauses removed.

Australia is now the only democratic nation in the world that has a constitution with clauses that still authorise discrimination on the basis of race.

For example, in 1998 the High Court had to decide on a case which addressed the changed sections of the Constitution. Despite the changes, the government was allowed to pass a law that was detrimental to, and discriminatory against, Aboriginal people. [27] In the Hindmarsh Island High Court decision Justice Kirby made it very clear that Section 51 (xxvi) can be used to the detriment and not always for the benefit of any race.

As Aboriginal people realised that the promises of the constitutional change were not going to be met, they started to organise and to protest: The Tent Embassy was established and the modern land rights movement was born. But these are other stories.

Although the 1967 referendum has failed politically, historically is was, and remains, a triumph of the human spirit that continues to inspire generations of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people alike. It is one of the glowing coals that keep the fires burning.

The ABC maintains a mini-site with a lot of in-depth information about the referendum.