Language

Aboriginal language preservation & revival

Language initiatives emerge aiming to protect and revive First Nations languages, including online projects. They are urgently required: many languages are under threat of dying with their last speaker.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Why do we need to preserve First Nations languages?

Traditionally, young children, who could pick up languages easily, were to become caretakers of several languages.

But many First Nations languages and dialects became extinct because their speakers were forbidden to use native language over many years under white Australian assimilation policies. If they belonged to the Stolen Generations they were removed from their family and community (often at a young age) and thus forgot their mother tongue.

Fewer and fewer First Nations people are also speaking an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language at home. While 16.4% did so in 1991, this figure declined to 9.8% in 2016. [1]

For example, in 2014, the Noongar people numbered more than 40,000 but with less than 250 fluent speakers of Noongar the language is considered endangered. [2]

The many challenges of reviving Aboriginal languages

There are many language preservation activities available, such as

- teach and promote a language,

- produce a book,

- create a dictionary,

- collect all known sources,

- conduct workshop recording elders speaking,

- produce and direct films, and

- produce classroom resources.

People interested in the preservation of Aboriginal languages find themselves working backwards from how English speakers spelt the sounds of traditional languages to rediscover what the sounds really were. [3] Sometimes all experts can work off is a dictionary written by missionaries. [4]

Besides spelling, meaning of words also needs to be translated back.

To date the linguistic semantics of Australian Aboriginal languages have not been analysed in any detail. [5] Linguistic semantics describe the ways in which humans employ grammar to express concepts such as past/present/future, the sequencing of events, and necessity and possibility. Local radio broadcasters take on a role as Aboriginal language preservers when they communicate information in the first language of their listeners. 42% of people in the Northern Territory listen to community radio each week [6] showing how valuable a first language service is to them.

Besides revitalising a language, training courses also teach core values of Aboriginal culture, often as a side effect.

"Since running these courses to teach and revitalise our Wiradjuri language, we can see our students adopting important elements of our culture that we call Yindyamarra, which means to show patience, respect and honour, and to be courteous," reports Stan Grant Snr, a Wiradjuri elder. [7] "This is a vital part of behaviour to the traditional people of the land and of our culture and heritage."

Even if a language can be reconstructed from old translations it is missing contemporary words. What would you call a 'computer', a 'mobile phone' or 'television'?

Researchers who were reviving the Kaurna language of South Australia's Adelaide plains had to get creative. They created 'muka karndo' (lightning brain) for 'computer', 'waratyatti' (voice sending thing) for 'telephone' and 'turraityatti' (picture sending thing) for 'television'. [8]

More than 150 Aboriginal languages have been completely destroyed by colonisation and only 18 languages remain intact to this day, but scores of languages thought effectively lost are being restored as long as researchers can find 500 to 2,500 words. [2]

Without intervention, Indigenous language knowledge will cease to exist in Australia in the next 10 to 30 years.

— Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner in 2010 [9]

Benefits and rewards of preservation

There are great rewards in reviving and preserving an Aboriginal language, as Kaurna elder Stephen Gadlarbardi Goldsmith explains:

"People ask me can you speak your language? Can you throw a boomerang? And I always felt it caused a lot of anxiety and frustrations, but now that I can speak, beginning to speak my language I've learned a couple of cultural activities as well. So when I'm asked today I have a different attitude - it's not that frustration and anger, it's a pride, that yes I can speak a bit of my language, and yes, I can do this, I can light a fire with fire sticks, I can do this." [8]

Other community members agree that the revitalisation of their language has strengthened their connection to culture. Some are learning how to deliver Welcome to Country greetings in language. [8]

Learning even a little of a First Nations language can increase participation in cultural activities and events by 79%. Speaking language makes people feel happier and full of life and energy. [10]

Reviving languages in Aboriginal communities can also lower suicide rates and improve mental health. Research has linked loss of language with self-loathing and higher rates of suicide. [4]

"I believe that the loss of language is more severe than the loss of land," says linguistics expert Professor Ghil'ad Zuckermann. [4] "Language death in my view means loss of cultural autonomy, loss of spiritual and intellectual sovereignty, loss of soul."

Video: Kaurna Language Learning series

Learn some traditional Kaurna greetings.

It's a terrible tragedy that most of the [Aboriginal] Australian languages are dead and will never be spoken again and yet we don't seem to be terribly worried about how we ensure the vitality and the ongoing viability of the languages we still do have.

— Prof Michael Christie, School of Education, Charles Darwin University [11]

The Kriol Bible ('Kriol Baibul') is the first complete bible in an Aboriginal language. [12]

Language preservation projects

Language preservation projects can address three main areas:

- First language support catering for people whose first language is still spoken as the main or one of the main languages of everyday communication in their communities.

- Language revival catering for people learning Aboriginal languages in various stages of recovery and revitalisation by their owners or custodians.

- Second language support catering for people learning an Aboriginal language.

Below are some sample projects dedicated to preserving Aboriginal languages.

Talking books: sound printing

Sound printing is a technology where a hand-held scanner (also known as a 'Talking Pen') reads tiny codes embedded in the pages of a book. It then plays back the corresponding sound file stored on a memory card inside the scanner. [13] Sound files are in a proprietary AP4 format.

Between 2011 and 2015 about 70 sound-printed books have been produced in Australia, mainly by Aboriginal organisations using the technology to improve literacy and maintain language. [4]

The technology originates in Taiwan where it was developed to help teach English. It is much cheaper than traditional printing.

Dictionaries

Dictionaries are a popular approach to record and preserve Aboriginal languages for future generations. Some such efforts grow out of Aboriginal community efforts to revive their language. [14] In being relevant to Aboriginal people's own needs and interests dictionaries encourage them to read and learn.

- Working closely with communities and linguists, Alice Springs-based Aboriginal publisher IAD Press created a Picture Dictionary series. The books include English translations of the Aboriginal words, accompanied by culturally appropriate illustrations and a pronunciation guide.

- The Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre has published a simple web dictionary of the Kunwinjku language (spoken by around 2,000 people in West Arnhem Land, Northern Territory).

- 50 Words is a website that aims to show the diversity of Aboriginal languages, starting with 50 words (or fewer, if more words aren't available). When it launched in August 2019 there were 15 languages, with hopes to eventually include every Aboriginal language. The site has audio and you can search a map of Australia by language and word.

Apps

There are several apps helping to keep Aboriginal languages alive.

Ma Gamilaraay, for the Gamilaraay language of south-east Australia, contains a dictionary of over 2,000 Gamilaraay words, and searches can be made in both English and Gamilaraay.

The other app, Ma! Iwaidja, covers the Iwaidja language of Croker Island in the Northern Territory. Ma Gamilaraay and Ma! Iwaidja are available free of charge at iTunes.

Wunungu Awara

Launched in 2011 at Monash University, and originally called the Monash Country Lines Archive, Wunungu Awara is a Yanyuwa term that means "a strong and healthy, a vital place".

The project targets especially the younger generations to reengage their interest in languages and uses 3D animation as a tool to revitalise interest via story-telling and songs.

Watch a sample video: Yagun Gulinj Wiinj (How Man Found Fire), about 8 minutes.

Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages

The Living Archive of Aboriginal Languages is a digital archive of endangered literature in Australian Aboriginal languages from around the Northern Territory.

It maintains connections to the people and communities who created the books it collects. This will allow for collaborative research work with the Aboriginal authorities and communities.

There are already hundreds of items in 25 languages from all over the Northern Territory.

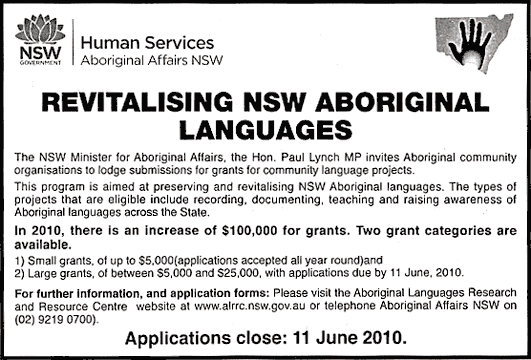

NSW Aboriginal Languages Research and Resource Centre

NSW is Australia's only state with its own Aboriginal language policy. [15] In 2004 it introduced a policy to encourage school students to study an Aboriginal language from Kindergarten to Year 10.

To help implement the policy it created the Aboriginal Languages Research and Resource Centre to give technical and creative support to teachers, students and Aboriginal communities. It set up an Aboriginal languages database and guidelines to help schools liaise with Aboriginal communities.

In 2008 the program was running in 35 schools throughout NSW. [15]

While there is a lack of Aboriginal language teachers the program has helped employ several Aboriginal people throughout the education department.

In Europe the idea of being multilingual is natural, but in Australia there's been a decline of interest until recently.

— John Hobson, course coordinator, Koori Centre, Sydney University [15]

Master-Apprentice language learning program

Master-Apprentice programs pair a (mostly elderly) master and an apprentice who belong to the same language group. Through training while living their everyday lives the master develops skills in teaching and the apprentice in learning the language. [16]

The program was developed after Aboriginal people in California, USA, decided they needed a way to revive their languages. It is highly effective in rebuilding communities of speakers of Aboriginal languages.

The first such program in Australia started in March 2012 in Alice Springs.

Yuwaalaraaly and Gamilaraay language project

Thankfully some initiatives are under way to try to revive or conserve some languages. One of them is the Yuwaalaraaly and Gamilaraay language project which tries to teach these northern NSW Aboriginal languages to children. The project's website offers stories spoken in these languages, the English translation and some background information on their history.

Miromaa computer program

A computer program, called Miromaa (meaning "saved" in the local Awabakal language of the Newcastle/Hunter region in NSW) has been developed by and for Aboriginal people.

It is being used nationally and internationally to support the preservation of more than 70 languages and dialects. [17]

The Miromaa program enforces good archive practise and helps gather any and all evidences of language including, text, audio, images and video.

The program is unique and nothing like it can be found anywhere else in the world.

— Daryn McKenny, Arwarbukarl Cultural Resource Centre [17]

Many Rivers Aboriginal Language Centre

Another resource is the Many Rivers Aboriginal Language Centre which aims to support Aboriginal languages on a coastal strip from Brisbane to Sydney.

Ngapartji Ngapartji

This language preservation project (speak: 'napatji napatji') was both a stage performance and an online interactive experience.

You could journey into Pitjantjatjara (speak: 'pidjnjara') culture and language by watching short films or songs that have been produced by Aboriginal community members and artists. Each clip or song was accompanied by a list of Pitjantjatjara words with their English meanings, pronunciation guides and even guided worksheets.

Numerous private language preservation initiatives rarely make it to the headlines. If you are interested it's a good idea to search for Aboriginal language forums.

[This] is a call to tongues, to learn our languages, find its secrets and remember them.

— Bruce Pascoe, Aboriginal writer and teacher [18]

Graduate course about Yolŋu language

There are about 8,000 speakers of Yolŋu languages in east Arnhemland. After English, Yolŋu Matha is the by far most commonly spoken language in the Northern Territory.

At Charles Darwin University people from around Australia and overseas learn about Yolŋu language and culture by enrolling in the Graduate Certificate in Yolŋu Studies.

This graduate course is designed to provide an introduction to the life and languages of the Yolŋu nations who live in north east Arnhemland. The Yolŋu Studies program at CDU is taught by a Yolŋu lecturer, from an Aboriginal perspective and has been approved by Yolŋu educators and elders. The course covers: pronunciation, spelling, Yolŋu names, basic conversation, grammar, maths, kinship, creation and history, land and ceremony, general principles for communicating with Yolŋu, politeness, respect, rights and responsibility in decision making and negotiation, Aboriginal philosophy of knowledge, education and science. The program is available for study both internally and externally.

More resources

Holding Our Tongues

Holding Our Tongues is a project about the long and painful task of reviving Aboriginal languages.

You can listen to examples of language and watch archival videos. The project aims to bring as many of language revival resources as possible together in one place.