Law & justice

Aboriginal prison rates

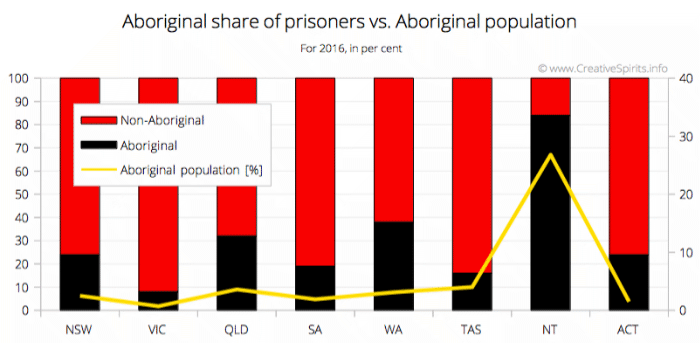

Aboriginal people are massively overrepresented in the criminal justice system of Australia. They represent only 3% of the total population, yet more than 29% of Australia's prison population are Aboriginal.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

-

29% - Percentage of Aboriginal prisoners in Australia in late 2019. [1]

-

34% - Percentage of all incarcerated women in Australia who were Aboriginal in 2016; of incarcerated men: 26.7%. [2]

-

48% - Percentage of juveniles in custody who are Aboriginal. [3]

- 50

- Number of reports that have been written on Aboriginal prison rates over several decades. [4]

-

59% - Percentage by which imprisonment rates increased for Aboriginal women between 2000 and 2010; for Aboriginal men: 35.2%, non-Aboriginal women: 22.4%, non-Aboriginal men: 3.6%. [5]

-

47% - Percentage by which the number of Aboriginal people in prison in NSW increased between 2013 and 2020. [6]

- 15

- Factor by which Aboriginal people across Australia are more likely to be imprisoned than non-Aboriginal people. [7] Same figure for WA: 20 times.

-

6.7% - Incarceration rate of Aboriginal men in Western Australia in 2008. Same rate for Aboriginal women: 0.6%; for African-American women in the US: 0.5%. [8]

- 20

- Times Aboriginal women are more likely to be in prison than non-Aboriginal women. [9]

- $7.9b

- Annual cost of Aboriginal overrepresentation in Australian prisons in 2019. [9]

- 3.2

- Times Aboriginal drivers in WA receive fines more often from being pulled over than non-Aboriginal drivers. Speed-camera-issued fines are even. [10]

- 19.2

- Factor by which an Aboriginal driver is more likely to be fined for seatbelt offences than non-Aboriginal drivers. [10]

-

75% - Percentage of Aboriginal prisoners who have been in prison before; percentage for non-Aboriginal prisoners: 50%. [11]

-

90% - Percentage of Aboriginal prisoners who are male. [1]

- 11

- Factor by which an Aboriginal defendant more likely to be refused bail by a court. [6]

Aboriginal prison statistics: "Every year it gets worse"

Since 2004, the number of Aboriginal people in custody has increased by 88% compared to a 28% increase for non-Aboriginal Australians. [12] In 1992 one in seven prisoners was Aboriginal. [13] By 2020 that ratio had risen to one in four. [14]

Australia's proportion of adult Aboriginal prisoners ranges from 9% in Victoria to 84% in the Northern Territory. [11]

Australia owns a humanitarian crisis as the mother of jailers of its First Peoples.

— National Suicide Prevention and Trauma Recovery Project in 2020 [14]

Australia is now facing an Indigenous incarceration epidemic.

— Former prime minister Kevin Rudd, in 2015 [15]

We are at a state of emergency, we can't afford any more experiment.

— Shane Phillips, Tribal Warrior Association, about Aboriginal prison rates [16]

The Alice Springs Prison is so far beyond capacity that it's refusing to take prisoners.

— Mark O'Reilly, principal legal officer, Central Australian Aboriginal Legal Aid Service, in 2011 [17]

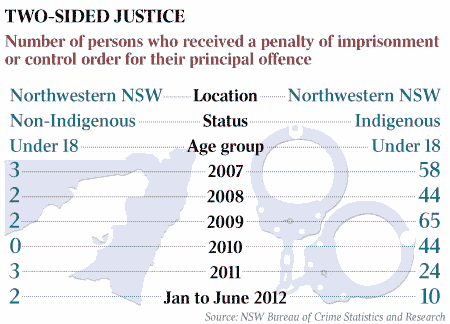

As the chart above shows Aboriginal people represent on average 17% of the prison population except in Western Australia and the Northern Territory where they account for 43% and 84%.

Yet, as the yellow line shows, Aboriginal people make up less than 5% of each state's population except for the Northern Territory where they account for 31.6%.

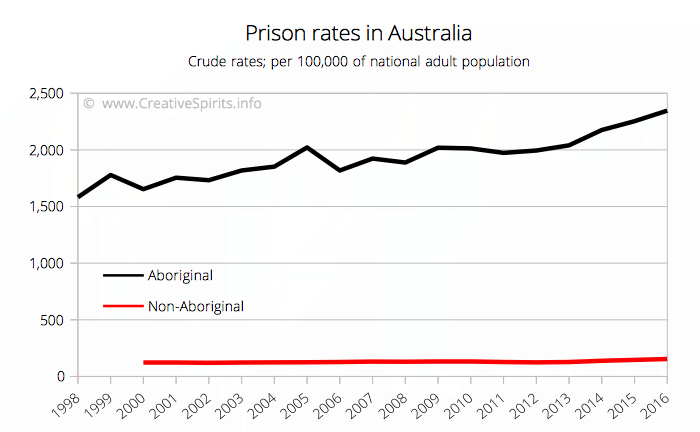

Since 1989, the imprisonment rate of Aboriginal people has increased 12 times faster than the rate for non-Aboriginal people. [19] In December 2019 the rate was 2,536 prisoners per 100,000 adult Aboriginal population, compared to 218 prisoners per 100,000 non-Aboriginal population. [1]

The most common offence or charge for Aboriginal prisoners was acts intended to cause injury (34%) followed by unlawful entry with intent (14%). The most common offences for non-Indigenous prisoners were Illicit drug offences (20%) and acts intended to cause injury (18%). [11]

Half of the 10- to 17-year-olds in jails are Aboriginal. [21] More than 30% of all Australian Aboriginal males come before Corrective Services. [22] No wonder that 90% of all Aboriginal prisoners are male. [2]

In June 2016, 69% of Aboriginal prisoners were sentenced, and 31% were unsentenced. [2] This has changed little since. In 2019 the figures were 67% and 33% respectively. [1]

In 1992 there were 15,000 prisoners (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal), by 2012 that figure had doubled to 30,000, and in 2016 there were more than 38,800. The imprisonment of Aboriginal peoples skyrocketed from 1 in 7 of all prisoners in 1992 to 1 in 4 in 2012, and to nearly 1 in 3 in 2014. [23]

| Country | Rate* |

|---|---|

| Australia (WA Aboriginal only)** | 4,066 |

| Australia (NT Aboriginal only)** | 2,748 |

| Australia (Aboriginal only)** | 2,440 |

| USA (African-American only)*** | 2,207 |

| Australia (NT only)**** | 886 |

| USA | 698 |

| Thailand | 461 |

| Russian Federation | 445 |

| Australia (WA only)**** | 335 |

| South Africa | 292 |

| New Zealand | 194 |

| Australia** | 216 |

| United Kingdom (England & Wales) | 148 |

| China | 119 |

| Canada | 106 |

| Germany | 78 |

| Indonesia | 64 |

| Finland | 57 |

* Per 100,000 of national population; sources: [24], ** [25], *** [26].

Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows that, from 2000 to 2012, imprisonment rates for Aboriginal Australians increased from 1,727 to 2,346 Aboriginal prisoners per 100,000 adult Aboriginal population. In comparison, the rate for non-Aboriginal prisoners increased from 122 to 154 per 100,000 adult non-Aboriginal population. [2]

And numbers are almost certain to be higher than reported. Australian Bureau of Statistics figures are a 'moment in time' measurement, yet many prisoners are in and out of prison more than once per year, making the numbers published by the ABS almost certainly wrong. Dr Fadwa Al-Yaman of the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare says simply “we are underestimating indigenous imprisonment”. [12]

Jailing Aboriginal people in such large numbers has numerous effects on their communities. For example, it prevents elders passing down traditional knowledge to the next generation.

The fact is, every year it gets worse.

— Gino Vumbaca, Executive Director, Australian National Council on Drugs, about Aboriginal prison rates [21]

The term 'mass-incarceration' is used to characterise the imprisonment of African American people in the United States, but incarceration of [Australian] Aboriginal women and children, in particular, are 20 times that.

— Charandev Singh, who assists families whose relatives have died in custody [27]

Prison rates highest in Western Australia

Western Australia always had a higher incarceration rate of Aboriginal people compared to the rest of Australia, and rates have nearly doubled between 1990 and 2010. [28]

A parliamentary report in 2010 found the rate of Aboriginal people jailed per 100,000 people in Western Australia was 2,483, while the figure for African Americans in the United States is 2,290 [28]. In March 2009 Western Australia's rate was 3,741. [29]

Perth based academic, prison reform advocate and restorative justice specialist Dr Brian Steels suggests that Western Australia's high prison rates could be related to the "frontier mentality" of police or racism. [7]

When researching police relationships with Aboriginal people, a disproportionate number of incidents occurred in Western Australia.

Western Australia incarcerates the Aboriginal peoples of its State at 9 times the rate of Apartheid South Africa.

— Gerry Georgatos, Human Rights Alliance, Perth [30]

What you cannot get away from is that the rate of Indigenous imprisonment in Western Australia is far greater than anywhere else in the country and indeed it compares with the worst rates of imprisonment, of African Americans in the United States.

— Bob Debus, chair of the federal inquiry into the over-representation of Indigenous young people in the criminal justice system [31]

Reoffending rates are high

With high levels of alcohol and substance abuse, lack of services of any kind, high unemployment rates, low levels of education and child abuse it is no surprise that there is a high rate of reoffending. In fact, repeat offending and re-incarceration is a large contributor to this high rate of imprisonment. [13]

The re-conviction rate within two years in NSW is 74% of non-Aboriginal people, and 86% for Aboriginal people. [32] In Western Australia, 80% of jailed Aboriginal male juveniles, 64% of Aboriginal female juveniles and 70% of adult Aboriginal males reoffend. [28]

"Research indicates that time in a juvenile justice centre is the most significant factor in increasing the odds of recidivism [reoffending]," says Father Chris Riley, founder of Youth off the Streets. [33]

Australia-wide, about one in four prisoners will convicted again within 3 months of their release from prison, between 35 and 41% within 2 years. [34]

ABS figures show that nearly three-quarters (74%) of Aboriginal prisoners had a prior adult imprisonment under sentence, compared with just under half (48%) of non-Aboriginal prisoners. [7]

A study of incarcerated women revealed that 67% of all Aboriginal women in prison had been incarcerated previously, while almost half this number of non-Aboriginal women had a history of incarceration. [5]

The lack of housing and support women receive upon release contributes to the high levels of re-offending. [27]

Looking after prisoner's mental health is key to cutting recidivism. In 2012, up to 80% of all inmates in Australia suffered some form of mental illness. compared to just 50% in 2003. [34]

Story: Why prisoners reoffend: An inside story

Michael Woodhead is a non-Aboriginal journalist whose young son in 2019 served a 4-year prison sentence for a first-time drug offence. Michael shares why he believes prisoners reoffend at such high rates. [35]

- No rehabilitation programs. Prisoners get no programs, no education and no training.

- No mental stimulation. Prisons offer few books, have no internet access and ban educational material from the outside. Almost all NSW prison teachers were sacked in 2016. Prisoners on remand have no access to anything educational. "There's nothing to do in prison except drugs, play cards or work out in the yard."

- Undemanding jobs. Prison jobs are often unskilled and undemanding, making prisoners yearn for "intense enough" jobs to help pass time.

- Us-versus-them regime. Prisoners stick together against the "blues" (prison guards). This means the role models and mentors are gang members, bikies and fraudsters, who impress their attitudes and knowledge on young prisoners. This will be what they take to the outside on release day.

- Condescending attitudes. The prison system often regards inmates as "oxygen thieves" and treats them as criminals who will never change, with no hope of reform.

56% of released prisoners in NSW reoffend and reenter jail within two years.

The Summertime Bathurst Blues

In the morning breeze, I hear the sounds, of early spirit bird tunes As the sun shines in, the walls cave in, and light out glows the moon. Guards stroll up, the wing gates bang, the day has now begun Half restless dreams, that should have been. I live 'em I believe I can I miss the waves, down near caves And watch the news, But I'm in here, all alone With the summertime Bathurst Blues

Poem by Reuben Scott, Bathurst [36]. Aboriginal singer Vic Simms sung his way out of Bathurst Jail. Read more Aboriginal poetry.

Why are prison rates so high?

To understand these high rates, one must know Aboriginal history. Many factors work together and some of them include the following: [38]

- Stolen Generations. Those taken away from their families as a child are twice as likely to be arrested than their peers. Some courts at sentencing don't consider when offenders are traumatised, for example being a victim of domestic abuse. [27]

- Disconnection from land. When Aboriginal people are not able to live on their traditional lands they are more likely to come into conflict with the law.

We cannot flee persecution to another country because we are spiritually connected to our own ancestral lands. So jails and mental institutions are full of our people.

— Wadjularbinna Nullyarimma, Gungalidda Elder and member of Aboriginal Tent Embassy [39]

- Police behaviour. Police might act racist, violently or inappropriately (see below for more on this).

- Offence criminalisation. Aboriginal people are 15 times more likely to be charged for swearing or offensive behaviour than the rest of the community.

- Social and economic situation. Poverty and unemployment, particularly for young Aboriginal people or in rural and remote areas ('crimes of need').

- Inadequate legal representation. Legal representatives have little time with their clients and Aboriginal defendants are sometimes unsure whether their lawyer is friend or foe. [12]

- People's attitude. Some police and community members have a "law and order" attitude.

We need to be clear, when they talk about 'tough on crime' they mean 'tough on Aboriginal people'.

— Vickie Roach, Yuin Nation, Women's prison rights advocate [27]

- Lack of language skills. Some Aboriginal people are sentenced to jail without them fully understanding the court process because English is not their first language. [40][12]

- Fetal alcohol syndrome. Many children enter the justice system because their mother drank too much alcohol during her pregnancy. Her children are often unable to appreciate the consequences of their actions [31] and do prostitution or theft, or both. [41]

- Health problems. Life expectancy and overall health are linked to prison and incarceration. Particular health issues drive imprisonment rates, notably mental health conditions, alcohol and other drug use, substance abuse disorders and cognitive disabilities. [42]

- Family breakdown and violence. "You can do whatever you like [to help a young offender]," says Queensland barrister Cathy McLennan, "but if they’re going home and getting bashed at night, if they’re going home and they are starving, they’re going to reoffend. That is the reality." [41]

- Disintegration seems to manifest in deliberate attempts to strip away Aboriginal culture in some communities. [16]

- Lack of accommodation. The Children's Court is often being told imprisonment was the only option. [16]

- Inflexible funding. Bureaucracy prohibits progress when programs cannot go ahead due to red tape. [16]

- Reoffending. Across Australia more than 70% of prisoners (Aboriginal or non-Aboriginal) reoffend. 38% are back in prison 2 years after their release. [43] This is why Aboriginal incarceration is called 'cyclical'.

- Inflexible sentencing Acts. Sentencing options in most, if not all, sentencing Acts are limited and lack flexibility, leading to a high rate of recidivism. [12]

- Lack of community services. According to The Medical Journal of Australia, "there is increasing evidence that many people in prison are there as a direct consequence of the shortfall in appropriate community-based health and social services, most notably in the areas of housing, mental health and well-being, substance use, disability and family violence." [22]

- Childhood and intergenerational trauma. Leading child psychiatric expert Stephen Stathis observed how lasting and profoundly damaging effects of trauma on children up until the age of three – which in some cases causes permanent brain damage – is connected to adolescent criminal offending. [41]

- Lack of government action. Solutions to lower Aboriginal prison rates already exist in the 50 different reports that have been written on the issue over several decades. But "there seems to have developed a culture of reporting in lieu of doing," as Tony McAvoy SC puts it, a barrister of the NSW Bar Association and the first Aboriginal Senior Counsel (SC) appointed in Australia. Several "reports provide a guidebook on how to reduce over-incarceration". [4]

There's no doubt that prison has a ripple effect on every family, especially if the member in prison was supporting the family.

— Justice Valerie French, chairman Prisoners Review Board [44]

Story: "He has never had an adult birthday"

William Bugmy, an Aboriginal man from Wilcannia NSW, first entered juvenile detention when he was 12 years old. [45]

He has a history of domestic violence and separation from family and placements in foster care. He also has mental health and health issues and started using drugs and alcohol from age 12, self medicating for years to “block the voices out”.

Mr Bugmy never been to residential rehabilitation, despite requesting it. He self-harms. He does not read or write. He has not had much education.

He spent most of his teenage years ‘inside’ before transitioning into the adult system often because of altercations with the police.

He has never had an adult birthday in the community. He is 31 years old and from a community where the average life expectancy for a man is 37. Many of his family members are already deceased.

“First jailed at 12 years of age for a six week stint, Mr Bugmy’s life thereafter shows the destructive effect of prison on people, families and communities,” says Solicitor Stephen Lawrence.

Non-Aboriginal people are indifferent

The other side of why Aboriginal prison rates are high appears to be through the indifference of non-Aboriginal people.

Australian governments rely blindly on their departments to find a solution without guiding them. In the past, however, many departments have learnt to exploit this freedom to protect their own interests, rather than those of incarcerated Aboriginal people. They become self-protective and self-preserving.

Police remain hard-hearted and indifferent to prison rates and, in some cases, Aboriginal prisoners themselves. Recommendations of the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody were cherry-picked for those that could be accepted without too much change occurring [46].

Aboriginal educator Chris Sarra believes Australians should stop seeing Aboriginal people as a separate group. He writes in The Guardian:

"There are mainstream Australians, and then there are the 'other' Australians. Casting Indigenous Australians as a negative and despised form of 'other' explains how we can tolerate or completely ignore such dreadful incarceration rates. Against this background it is very simple to make such pious and ill-considered statements as, 'If they don’t want to go to jail, they shouldn't break the law!'" [47]

You have government departments who say, 'just lock them up. that will solve the problem'.

— Joan Baptie, Magistrate and convenor of the Youth Drug and Alcohol Court of New South Wales [16]

"Incredibly trivial offences"

There is a persistent feeling among Aboriginal communities and legal experts that police treat Aboriginal people differently for trivial offences.

Would you be going to jail for any of these things:

- Did not receive court mail. Some Aboriginal people end up in jail because they did not get the postal notifications of court dates after which bench warrants are issued and bail is unlikely. [48]

- Can't make it to court. Others simply cannot make it to a court date due to funerals or health problems and courts are too inflexible to change the date. [49]

- Unpaid fines. A young Aboriginal woman was held for four days because she hadn't paid her parking fines. [50] Tragically, in this case, the woman died a short time after. According to one Western Australian prison attendant, their prison receives "seven or eight [new inmates] a day" because of unpaid fines, most of them women. [51] An average unpaid fine is about $3,000 with much of it additional fees and charges. [9] (The WA government eventually passed legislation to prevent the imprisonment of fine defaulters in June 2020.)

- Driving unlicensed. Youth who might never have seen a traffic light or a freeway have difficulties getting a license because remote communities lack trainers and facilities, and the language used for driving tests is inappropriate. When they then get caught repeatedly driving unlicensed, uninsured and unregistered—a common “trifecta” on court lists—they end up in jail [52]. But in many Aboriginal communities only one person holds a drivers license.

- Driving during lockdown. During the corona pandemic, some First Nations people were fined for driving people who didn't belong to their household to the supermarket or to attend a funeral. But they might have been culturally obliged to do so.

In New South Wales, the Local Court is required to add a further 5-year disqualification period under the Roads and Traffic Authority Traffic Act's Habitual Offender Scheme introduced for people who commit 3 serious traffic offences in 5 years [53]. This means some people who collected too many offences in their youth might get disqualified from driving until they are for example 50 years old. This has dire consequences for the standard of living, finding work and managing children.

- Provocation by police. "There have been a number of instances where our men and women have been flogged or abused by police... When they're going off because of the abuse that's happened to them, they're being put down the back and they've got no support," says Marianne McKay, Co-deputy Chair of the Deaths in Custody Watch Committee of Western Australia [54].

Story: Jailed to die

48-year-old Marshall Wallace was given a 15-month prison sentence for a series of driving offences after being caught driving without a licence in Mount Isa. The problem was, Mr Wallace was terminally ill and had only 6 to 9 months to live, and his wife had a doctor's letter to prove it. The couple had moved to Mount Isa to access chemotherapy services.

It took a petition attracting 17,000 signatures, pressure from the public, media and lawyers, and the Federal Indigenous Affairs Minister Nigel Scullion writing a letter to the Queensland Premier asking to support early parole for Mr Wallace, to release him from jail. [55]

Police pursue Aboriginal people more

Aboriginal people are more likely to be charged, less likely to get bail and more likely to be given a prison sentence. There are some really gross injustices going on in the criminal justice system.

— George Newhouse, CEO of the National Justice Project and Adjunct Professor at Macquarie University and the University of Technology, Sydney [56]

"Every day of the week we act for Aboriginal people who've been charged with disorderly conduct," says Peter Collins, Legal Director of Aboriginal Legal Services in Western Australia (ALSWA). [57]

"Their crime: To swear at the police. They use the F word, they use the C word. Often they're drunk or affected by drugs or both, or they've got a mental illness or they're homeless or whatever. But it seems to me the only people in this day and age who are offended by the use of the F word and the C word are police. And so these [Aboriginal] people are hauled before the courts for these incredibly trivial offences."

In Wickham, Western Australia, Aboriginal people have been arrested for 'shouting'. [58] Many times, police challenge Aboriginal people into such behaviour.

And in New South Wales, police pursue far more Aboriginal people found with small amounts of cannabis through the courts: 82% compared to 52% of non-Aboriginal people who are more often let off with warnings. An investigation by The Guardian Australia found that "police disproportionately used the justice system to prosecute Indigenous people". The data shows police were four times more likely to issue cautions to non-Aboriginal people, and that 93% of Aboriginal people taken to court for the cannabis possession charge were either found guilty by a judge or magistrate or pleaded guilty. [59]

Australia continues to regard swearing as an offence. Queensland remains the only state in which a person can be arrested for being drunk in public. [60]

First Nations people are more likely to spend time in prison even if innocent, in some cases more than two years. [56]

In all my years of research in criminal justice, I can tell you it would be very difficult to find a white person charged with shouting or swearing.

— Dr Brian Steels, restorative justice researcher, Murdoch University [58]

Police "selecting" and locking up Aboriginal people for swearing is widespread and known as selective policing. Training about Aboriginal culture and awareness could assist police to find better responses.

According to Western Australia Police Commissioner Karl O'Callaghan police are not prejudiced against Aboriginal people or any other racial group. This, however, is a statement which meets little love among Aboriginal communities, and little validation by statistics.

Criminologist Chris Cunneen knows that Aboriginal people are more heavily policed and let off less under discretionary powers. Higher imprisonment rates are not reflective of higher crime rates but harsher sentencing, bail laws, and a move away from alternative sentencing measures. [27]

I've spoken to somebody who was arrested because he stole a [piece of] fruit. And another one who was [arrested for] sleeping in the trash bin.

— Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN Special Rapporteur, in 2017 [61]

Case Study: Read how swearing at police can not only land you in prison but also cost your life.

An Aboriginal man's death becomes the most prolonged investigation in the criminal justice system for an Indigenous community.

Further resources

Change the Record

The Change the Record campaign aims to close the gap in imprisonment rates by 2040. It is overseen by a steering committee, made up of Aboriginal, human rights and community organisations. It offers key statistics and case studies on its website.