Arts

Aboriginal rock art

Australia has some of the oldest rock art sites in the world. They offer a glimpse into extinct species, spirituality and relationships.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Aboriginal rock art facts

Australian Aboriginal rock art is world famous. Some of the oldest and largest open-air rock art sites in the world include the Burrup Peninsula and the Woodstock Abydos Reserve, both in Western Australia.

Engravings found in the Olary region of South Australia are confirmed to be more than 35,000 years old, [1] the oldest dated rock art on earth.

The Northern Territory's Limmen National Park in the Gulf of Carpentaria is home to some of the most detailed miniature rock art at a rock shelter known as Yilbilinji. Miniature rock art measures only centimetres across and is incredibly rare, with only two other examples of its kind in the world, one of which is at Nielson's Creek in New South Wales. [2]

Researchers assume that there are more than 100,000 significant rock art sites in Australia[1] and 5,000 in the Northern Territory's Kakadu National Park.

But there is no central register of Australian sites, and some spectacular places are known only to two or three people [1]. Only a third of Australia's Aboriginal rock art has been recorded. [3] China, South Africa, France, India and Spain all catalogue and protect their Indigenous art.

Rock art paintings found in the Djulirri rock shelter in north-west Arnhem Land chronicle Aboriginal contact with Maccassan traders from Sulawesi, believed to be the first visits to Aboriginal people from outside Australia.

The rock art also depicts early sailing ships, a World War II biplane, a bicycle and a gun, [4] a rare art form known as 'contact work'.

Researchers found Aboriginal rock art they claim is a cluster of engraved astronomical markers, found on a series of rock platforms, and without parallel in Australia, and perhaps the world. At least 16 major rock platforms contain no less than 3,500 star markers researchers believe represent the star pattern above Gosford around the year 2,500 BC. [5]

Some archaeologists call rock art "rock documents" or “a third archive", besides oral history and written documents. [3]

Australia needs a national rock-art heritage strategy—it has never had one. We need an inventory of the nation's rock art, a database that can be used to help manage and protect the art for future generations.

— Paul Taçon, Professor of Archaeology, Griffith University [3]

How did Aboriginal people engrave the rock?

Aboriginal rock engravings were cut into sandstone which geologically is a soft sedimentary rock. Aboriginal people first pegged holes along the outline of the figure which they then connected in a second step.

The true purpose of Aboriginal rock art

For non-Aboriginal people it is easy to view rock art as an individual piece of art. We admire the beauty and intricacy of it, then walk on to the next piece, just like in a museum.

Most Aboriginal art sites were not intended that way. They form an interconnected grid of sites, or places, which are all part of an overall story which is more than its parts.

A local rock art site might tell a particular creation story which is connected to another rock art site which might be a few hundred metres away. Some sites are a long distance apart yet still connected through the Dreaming stories they tell.

When energy giant Woodside Petroleum moved 170 ancient rock engravings to build a natural gas production plant on the Burrup Peninsula the company received 'intense criticism' from archaeologists. Moving the Aboriginal rock art would destroy their spatial arrangement, a clue to their interpretation: "Where carvings sit in the landscape is vital to understanding how people themselves interacted with the environment," says archaeologist Ken Mulvaney. [6]

You've got to think of [Aboriginal rock art] as the Aboriginal people think of it - as a whole. They see it as a place, they don't see it as individual rock art.

— Sue Smalldon, archaeologist [7]

Carvings can tell you many stories. They can tell you what food is in that area, and what you can eat in that land.

— Peter Stevens, Kurrama tribe, Western Australia [8]

Aboriginal carvings of women are extremely rare.

How do you identify an Aboriginal rock art site?

The location of many Aboriginal rock art sites has been lost over time. It needs the knowledge of old stories, traditional owners, elders and many volunteers to find them again.

Once an art site has been found one needs to identify what the artwork is about. The rock art is first photographed and the researcher makes themselves familiar with the area by walking around. They then talk to Aboriginal elders in that area, but also in other places. Sometimes stories are about the same ancestral beings, and Aboriginal people of Central Australia might be able to identify creator beings found on the east coast. [9]

Once the individual items of a site are identified it is important to get confirmation. With an understanding of each element, and the background of Australia-wide stories and history, it is then possible to map out the story that belongs to the art site one examines.

The process of identification of an Aboriginal rock art site is tedious and costs a lot of energy (and a significant amount of money). Dedicated archaeologists are able to identify about one site every 10 years. [9]

Bushfires help expose Aboriginal rock art. Sometimes new sites are discovered by bushwalkers. "New locations are being discovered all the time," says David Watts who works for the Aboriginal Heritage Office in Sydney. [10]

Multimedia gallery:Uncovering Aboriginal rock engravings

From exploiting to partnering: A new relationship with custodians

Early archaeologists worked with the mindset that they had authority over a dig site since the original occupants of the land were no longer around. Sites and artefacts, so the view, were of "universal significance" and access to them should be automatic. Archaeology in Aboriginal Australia thus earned a reputation as being exploitative. [11]

This is changing.

Before archaeologists from the University of Queensland dug in Kakadu National Park in 2015 (where they eventually found an artefact that rewrote the age of Aboriginal culture in Australia) they had to negotiate with the country's traditional custodians, the Mirrar people.

The Gundjeihmi Aboriginal Corporation asked the archaeological team to either share everything found at the dig site with the traditional custodians, or go somewhere else.

The archaeologists would also need to share their field notes and the images they took. The Mirrar would be able to influence editors in the way they portrayed the site and the Mirrar people in publications. The Mirrar would be included in decisions about how artefacts would be curated, and what would be returned to the soil. [11]

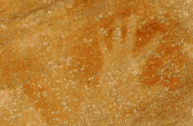

Hand stencils

Hand stencils are thousands of years old and very common in southern and eastern Australia.

Aboriginal people put a mixture of ochre, water and animal fat (sourced from emu, kangaroo or echidna) into their mouth and blew it across their hand which rested on a rock surface. The ochre chemically reacted with and sunk into the surface of the rock just like ink does into paper.

As these stencils were commonly made on rock walls of shelters or north-facing rock they were protected against weathering and lichen.

Today artificial drip lines made of pliable silicone direct dripping water away from the stencils. Metal viewing platforms avoid dust stirred up by visitors to be blasted by the wind against the rock art. [12]

Stencils reach their greatest art form in the Carnarvon Ranges in central Queensland where dozens of hand stencils were combined to produce complex patterns. [13]

Some stencils were left to mark a nation's territory or a hierarchy of importance.

Children's stencils are usually found in lower areas where they were made when the child was very young. Only after initiation were they allowed to place a second stencil. Elders were the only ones who could have the stencil of the entire forearm on a rock wall. [12]

The higher up a hand stencil on the rock, and the more of the wrist and arm appeared, the more important the person was.

Hand stencils dating back 2,500 years have also been found on the walls of Argentina's Cueva de las Manos (Cave of the Hands) in Patagonia, in France, Spain, Papua New Guinea, Indonesia's Gua Ham cave, in the Handprint Cave of Belize and Elands Bay Cave in South Africa. Handprints and stencils span all continents and began appearing on rock walls around the world at least 30,000 years ago. [14]

Interestingly you still find modern hand stencils these days—on city walls and in company logos.

The organisation Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR) also uses a hand to promote their goals. View a photo gallery of their Sea of Hands campaign.

Experiments have shown that right-handed people tend to make stencils of their left hands, because they use their right hands to hold the pigment tube or to help purse their lips to spray on the pigment. [14]

The Google Art Project shows a wonderful gallery of Australian rock art.