Economy

Successful Aboriginal businesses? You bet!

Aboriginal businesses can be as successful as any other. And they have one unique advantage when it comes to overcoming challenges.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

-

33% - Percentage of top 500 Aboriginal corporations located in the NT; in WA: 24%, QLD: 19% NSW: 13%. [1]

- $1.88b

- Combined income generated by the top 500 Aboriginal corporations; in 2009/10: 1.16b; in 2004/05: 0.77b. [1]

-

12.5% - Average growth rate of top 500 Aboriginal corporation's income per year in 2014/15. [2]

- 15,064

- Number of full-time employees in the top 500 Aboriginal corporations in 2016; figure for 2014/15: 11,095; for 2007/08: 6,948. [1]

-

43% - Percentage of self-generated income of top 20 Aboriginal corporations; government funding: 39%; other sources: 17%. [1]

- 8,900

- Number of Aboriginal people who were self-employed in 2011; [3] figure for 2006: 6,600. [4]

-

60.2% - Percentage of top 500 Aboriginal corporations making a profit. [1]

- 2,300

- Number of Aboriginal business operators in Australia in 2010. [5]

- 12,500

- Estimated number of Aboriginal-owned businesses in Australia in 2013; [6] in 2016: more than 16,000. [7]

-

31% - Increase of Aboriginal small-business owner-managers between 2006 and 2016. [8]

-

3.4% - Proportion of Aboriginal small-business owner-managers in Australia in 2016; of non-Aboriginal owners: 8.6%. [8]

- $3.40

- Dollar value of social value a sample of Aboriginal businesses provided in addition to their goods and services for every dollar of revenue. [9]

What is an 'Aboriginal business'?

Aboriginal businesses can employ both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal staff. Here are the Australian Bureau of Statistics' definitions to help decide when a business is Aboriginal: [10]

Definition: Aboriginal-owned business

An Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander-owned business has at least one owner who identifies as being of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander origin.

For this definition:

- a ‘business’ is defined to align with the ABS standard definition of a business

- self-identification is accepted for a person of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin.

The above definition includes businesses where there is equal ownership between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal persons (e.g. a mixed couple) or there is Aboriginal minority (less than 50%) ownership in a business.

Definition: Aboriginal-owned and controlled business

An Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander-owned and controlled business is one that is majority owned by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons.

For this definition:

- a ‘business’ is defined to align with the ABS standard definition of a business

- self-identification is accepted for a person of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander origin

- majority ownership is considered to be a proxy for control.

What characterises an Aboriginal business?

Supply Nation, a non-profit organisation that promotes supplier diversity, found the following to be true for Aboriginal businesses: [9]

- Aboriginal businesses are a "safe place" for families;

- Aboriginal businesses create economic independence;

- They enable their owners to build resilience and pride in their workplaces and communities;

- Businesses working directly in Aboriginal cultural industries return more social value than businesses working in mainstream industries, and smaller Aboriginal businesses return more social value than larger businesses;

- Aboriginal businesses employ more than 30 times more Aboriginal people than other

businesses; - Aboriginal-owned businesses strengthen their Aboriginal employees' connection to culture and allow them to thrive;

- Owners of Aboriginal businesses reinvest revenue in their communities;

- Aboriginal business owners who were part of the Stolen Generations use their businesses to create a place of belonging and healing;

- Aboriginal owners, employees and communities are proud of Aboriginal businesses;

- Most business owners are earning less than they could by working for somebody else.

We know what we want and how to get there and bring others with us. It’s about the collective, not the individual.

— Gordon Cole, GPSI and Cole Workwear [9]

Story: If you're in business we will steal you

Yuin man Nathan Martin, who founded a company that helps former inmates find a job, remembers how authorities discouraged Aboriginal business activity in the 1940s.

"For a long time Indigenous people couldn’t own businesses in this country. My great-grandfather was one of a handful of families that started the first Aboriginal-run newspaper, Abo Call, in 1938.

"The government stole every single child whose family was involved in that newspaper, my grandmother being one of them. They used that as an example: if you want to stand up against us, we’ll steal your children." [11]

A snapshot of Aboriginal businesses

The University of Melbourne published a snapshot of Aboriginal businesses in 2021, [12] data that it claimed "will dismiss the many stereotypes and myths" that still limit the success and opportunities of Aboriginal businesses. Here are a few key statistics from that snapshot.

Aboriginal businesses grow fast

Over the 12 years the study examined (FY 2006 – FY 2018), the number of active Aboriginal businesses grew by 74% from 1,841 to 3,619.

Year-on-year, the numbers have grown at roughly a constant rate of around 4.3% per year, but it strongly depends on the business location: Numbers grew 8% per year on average in cities, compared to 2% in remote and 3.7% in regional areas.

Around 60% of registered Aboriginal businesses were active in 2018, a rate that is similar to non-Aboriginal businesses.

Their gross income more than doubled from $2.27 billion to $4.88 billion, and in 2018 Aboriginal businesses employed twice the number of employees (45,434) than before (22,715).

Aboriginal businesses are larger

On average, registered Aboriginal businesses are larger than non-Aboriginal businesses. Their average gross income ($1.6 million) is four times that of non-Aboriginal businesses ($400K) and they employ on average seven times as many employees (14 compared to 2).

While only 9% of Aboriginal businesses of the dataset studied are sole traders, 32% of non-Aboriginal businesses are run by just one person.

Almost two thirds of Aboriginal businesses (72%) are registered companies, but only a third (33%) of non-Aboriginal businesses are.

About 80% of Aboriginal businesses employ less than 20 people, compared to 96% of non-Aboriginal businesses.

Aboriginal businesses abound outside cities

Only 42% of Aboriginal businesses operate in major cities, compared to 74% of non-Aboriginal businesses. Of the remainder, 32% are in regional and 26% in remote locations.

However, the remote Aboriginal businesses contribute 34% of the total gross income and 37% of all employment, an indicator of the many opportunities in mining and construction.

More than half of all Aboriginal businesses operate in one of the following sectors:

- Construction: 17%

- Professional, Scientific and Technical Services: 14%

- Health Care and Social Assistance: 10%

- Administrative and Support Services: 7%

- Rental, Hiring and Real Estate Services: 5%

- Education and Training: 5%

Aboriginal businesses help communities

An Aboriginal business not only supports its owners and employees, it has also significant benefits for the communities it serves or operates in. Some of these benefits include:

- Enhanced trust in services. Aboriginal businesses are best suited to deliver a range of services, including health and education services, in a culturally sensitive manner that builds trust and improves accessibility of services for Aboriginal people who rely on them.

- Extend the services on offer. Services provided by Aboriginal businesses benefit specifically regional and remote areas which are perpetually under-serviced.

- Preserving culture. Businesses which operate in art and tourism help preserve and educate Australians and international visitors about Aboriginal culture.

- Reduce Aboriginal unemployment. Aboriginal businesses are more likely than

non-Aboriginal businesses to hire Aboriginal employees, reducing unemployment rates but also helping to overcome discrimination, a major barrier for many Aboriginal people.

Since 2015, Indigenous Business Month celebrates every October how First Nations businesses are a pathway to self-determination, provide positive role models for First Nations peoples and improve the quality of life in First Nations communities. See indigenousbusinessmonth.com.au

Homework: What's going on here?

The snapshot of the University of Melbourne found that in regional areas only 4% of Aboriginal businesses operate in agriculture, forestry and fishing, compared to 21% of non-Aboriginal businesses.

- To prepare your examination, brush up your knowledge about Aboriginal people's relationship to land.

- A business needs access to, or ownership of, the land if it works in one of the above sectors. Check land ownership figures in Australia. Do they help explain the statistic above? Can you derive a more generic conclusion?

- Australia's native title process enables traditional Aboriginal custodians to claim land. Review maps of areas which have already been claimed. Do you see a connection between the potential business success and the productive quality of the land?

Aboriginal businesses: unique challenges, but a secret skill helps succeed

In 2006, 6% of Aboriginal people aged 15-64 years were self-employed; around one-third the rate for non-Aboriginal people in this age range (16%). The overwhelming majority operated in construction (26%), followed by transport, postal and warehousing (9%) and retail (7%). [4]

Most of the top 500 Aboriginal corporations operate in health and community services (40%), employment and training (26%) and land management (17%). [1]

With Australian media blasting out negative news about Aboriginal people it is difficult listening to the quiet stories of Aboriginal success in business. But they are everywhere, like refreshing oases dotting a dry media desert.

Challenges...

Research found that because Aboriginal people were for a long time not allowed to join mainstream economic activities they are generally poorer and only a select few were able to get formal business experience before the early 2000s. [8]

Thus many Aboriginal businesses have only formed after that time, and their stories are seldom told. The biggest challenge is educating local markets that Aboriginal businesses can add significant value to the economic landscape.

"Aboriginal people are succeeding in all sorts of things and we are trying to put these stories out there,” says Wayne Denning, a Birri Gubba man and Managing Director of Brisbane-based Carbon Creative agency. “We are working to initiate stories and ideas and being a leader in the way we do business." [13]

Aboriginal businesses operating on land purchased by Aboriginal land corporations sometimes face another challenge: Once land is purchased by the corporation and divested to another business, it cannot be sold — making it difficult to get a loan from the banks. [14]

Unlike non-Aboriginal farmers who often have been in business for generations, Aboriginal farmers acquire land after many years of separation from the land [14] and have to learn the skills from scratch.

A challenge unique to Aboriginal business owners is their Aboriginality. The media has been successful in equating Aboriginality with failure in many Australian minds.

While Australians have no problem acknowledging individual success, like that of sport legend Cathy Freeman, they struggle attributing it to their Aboriginality. But when Australians come to consider the perceived failings of an Aboriginal person, they almost always attribute it to their Aboriginality. [15]

Mainstream Australia looks at you and wonders why you are successful.

— Tess Atie, owner NT Indigenous Tours [16]

...and chances

Glen Brennan, a Gomerio man from Narrabri in northern New South Wales and State Director Victoria, Government, Education and Community with NAB, knows that Aboriginal businesses face the same sort of challenges as mainstream businesses. But he also knows they have a secret ingredient that helps them survive and strive.

"Indigenous businesses will be required to show the adaptability that made our old people here truly successful in this country for millennia," he reveals. "It’s that same level of adaptability that entrepreneurs are going to need to show in a world that’s continually changing."

"That ability... is what we are seeing now. It’s quite pleasing because that’s the skill set that’s required to develop scale." [13]

A "unique branding advantage" of Aboriginal farms is the growing and significant demand for Aboriginal-branded food products, for example honey and bush foods.

"The cultural relationship between land and people is what really resonates in the consumer side of things," says Kelly Flugge of Western Australia's Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development. [14]

Aboriginal businesses are also pivotal in recruiting Aboriginal employees. Data shows they are between 40 and 50 times more likely to hire Aboriginal employees than non-Aboriginal companies. [8]

If they were able to get a fair share of resource contracts in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, it would dramatically improve the social and economic fabric of every Aboriginal person in the region. [17]

"With employment, Aboriginal [businesses] recruit, retain and train more Aboriginal people than any other business group or sector in the country," observes Tony Wiltshire, general manager of the Pilbara Aboriginal Contractors Association (PACA).

"Aboriginal businesses are the best recruiter and trainers of Aboriginal people because they understand the cultural requirements and obligations and conditions and circumstances of Aboriginal people in the Pilbara far better than any of these [non-Indigenous] resources companies operating in the Pilbara." [17]

The Indigenous Procurement Policy, introduced by the Australian government in 2015, established targets for federal government departments to buy what they needed from Aboriginal suppliers. Since then the value of successful Aboriginal tenders increased from $6 million in 2012/13 to more than $1 billion in 2018. More than 1000 Aboriginal businesses are have contracts with the federal government. [8]

Being an Aboriginal person in business, there's nothing more involving and proud to be able to do [than] the thing you love and turn it into a business.

— Josh Whiteland, operator of Koomal Dreaming [18]

Operating areas of Aboriginal businesses

The distribution of Aboriginal businesses across operating areas is very similar to that of non-Aboriginal businesses as the following table illustrates. [3]

| Sector | Aboriginal businesses [%] | non-Aboriginal businesses [%] |

|---|---|---|

| All services | 43 | 44 |

| Construction | 26 | 20 |

| Wholesale & retail | 9 | 12 |

| Agriculture | 6 | 7 |

| Health | 6 | 7 |

| Manufacturing | 5 | 7 |

| Education | 4 | 3 |

| Mining | 0.9 | 0.4 |

Since 2007, the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations prepares a Top 500 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander corporations report which collates and compares a range of data provided by corporations as part of their annual reporting.

Where can you find Aboriginal suppliers?

More and more organisations and companies are implementing Reconciliation Action Plans (RAPs). A common element of their RAP is to liaise with Aboriginal suppliers. But where can you find them?

Supply Nation

96% - Percentage of Australian businesses that are small businesses. [19]

<1% - Proportion of small businesses that are Aboriginal-owned. [19]

Supply Nation (formerly known as Australian Indigenous Minority Supplier Council (AIMSC)) aims to encourage the growth of Aboriginal businesses by linking corporate and government purchasers with certified suppliers of goods and services. Similar overseas models have a proven track record in improving business and employment participation rates in minority communities. [20]

Supply Nation wants to ensure that small to medium Aboriginal businesses have the opportunity to be integrated into the supply chains of Australian companies and government agencies.

Commencing in 2009 as a 3 year pilot project, Supply Nation is a not-for-profit membership body and is funded by the Australian Government Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations, as well as Industry & Investment NSW.

After successfully completing the pilot phase, AIMSC rebranded to become Supply Nation in 2013.

In its 2014 annual report, Supply Nation had 276 certified suppliers on its books generating $105m worth of contracts and $107m of transactions. [21]

Black Pages

Founded in 1999, Black Pages is Australia's first national Aboriginal business and community enterprise directory. It's a marketplace for businesses, government agencies and communities.

As an Aboriginal-owned business, it builds and promotes Aboriginal business entrepreneurship and works with government, industry and communities to improve socio-economic development and outcomes for Aboriginal people.

Apart from listing Aboriginal businesses, Black Pages also includes supportive non-Aboriginal businesses, government agencies and other groups.

Success stories

Indigenous Land Corporation purchases Ayers Rock Resort

15 years after Uluru was handed back to its traditional owners the Indigenous Land Corporation (ILC) announced on 15 October 2010 that it had purchased the Ayers Rock Resort and all associated infrastructure for A$300 million. [22]

The deal, although having been subject of inquiries and controversies, was a big step towards Aboriginal self-determination in Central Australia. Through a local organisation, the Anangu people acquired a stake in the enterprise and now play a role in resort operation and management.

A year later, in 2011, the ILC established a national Indigenous tourism training academy at Yulara.

We have watched the resort be built and grow over the last 30 years, but Anangu were always outside. We hoped that the resort would provide training and jobs for us, but that's never really happened.

— Margaret Smith, Chairperson, Wana Ungkunytja [22]

- 1

- Number of Aboriginal staff at Ayers Rock Resort in 2010 [22]; in 2012: 170 [23]; in 2015: 211 (34% of staff). [24]

- 340

- Projected number of Aboriginal staff at Ayers Rock Resort for 2018: 340 (or 50%). [22]

- 400,000

- Annual number of tourists visiting Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park. [22]

- 1985

- Year Uluru was handed back to traditional owners (26 October 1985).

Tour operator

Tess Atie is the owner-operator of NT Indigenous Tours. Two years after starting her own business she now understands the business world and attends meetings and networking functions. [16]

Tess received support from Indigenous Business Australia (IBA) which helped her write a business plan and gain accreditation to operate out of Kakadu National Park. She took out a loan to finance her tour vehicle, contrary to some people's belief that she received it from the government.

Imparja Television

Imparja Television is an Aboriginal-owned broadcasting station in Alice Springs, NT, operating since June 1988. Its services include National Indigenous Television (NITV) which was launched in mid-2007, and eight Aboriginal radio stations [25].

Nine Imparja has the largest broadcast area in Australia, covering 3.6 million square kilometres across six states and territories with an estimated audience of 430,000 people. It comes free-to-air and competes with the national market for advertising revenue.

Indigenous Business Australia (IBA)

Indigenous Business Australia is a government agency which

- assists and enhances Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander self-management and economic self-sufficiency and

- advances the commercial and economic interests of Indigenous people by accumulating and using capital assets.

One of the tasks of IBA is to help Aboriginal people achieve home ownership. In 2001 Indigenous home ownership was at 32% while the national non-Indigenous average was 68% [26]. IBA wants to raise this rate to 40%. In 2008 its customers come from NSW (29%), QLD (27%), NT (16%), VIC (10%) and WA (8%).

Business high-flyers join Aboriginal communities

In 2001, Westpac and the Boston Consulting Group launched Indigenous Enterprise Partnerships, renamed in 2010 to Jawun (meaning "friend" or "family"). Jawun brings together business people with Aboriginal communities.

Usually sent out on 5-week assignments, the corporate experts find the holes in local know-how and match business experience to the community. Among other things they help run businesses professionally, improve board reporting, deal with governments or secure grants [27].

Businesses involved include KPMG, IBM, Wesfarmers, Rio Tinto, Leighton Holdings, Woodside, BHP Billiton and Qantas. Projects operate in Cape York, Arnhem Land, the Central Coast, inner Sydney, the Kimberley or the Murray area.

Store remake saves 600km round-trip

People from the Jilkminggan community in the Northern Territory who wanted to buy good food for their families had to travel 300km to Katherine and back because their store's stock was mostly unusable and very expensive [28].

The local Dungalan Aboriginal Association decided to improve the situation. Together with Outback Stores and the Federal Government Department of Families, Housing, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs (FaHCSIA) the community store was overhauled and re-opened, meeting all safety and health requirements.

The new store now has a good chance of making a strong return for the community and delivering better health outcomes for the people.

Jilkminggan is just one of those success stories where you see absolute co-operation with the community, the government and Outback Stores.

— John Kop, CEO Outback Stores [28]

Story: Daniel was sick of small jobs

When Daniel Tucker and his brothers were trying to break into the mining industry, they found people were often reluctant to give them work in the industry.

Instead they offered them minor jobs like gardening and fencing.

Rather than become discouraged, the brothers were inspired to establish their own mining company—Carey Mining—in 1995.

Carey Mining now has contracts with big companies such as BHP Billiton Nickel West and Rio Tinto, and also runs a training scheme for Aboriginal students.

In 2010 Carey Mining won the inaugural Indigenous in Business Award at the Ethnic Business Awards ceremony in Perth [29].

The above story is not unique. "Aboriginal people want real jobs," says Alison Anderson, a Northern Territory politician and Independent Aboriginal MP [30]. "They want to be trained as plumbers, as carpenters, instead of bringing in people from the outside to take all the money."

Many Aboriginal people have "up to six or seven certificates" from training but still cannot get a "real job" Anderson observes.

Successful farm

Dowrene Farms, part of Western Australia's Noongar Land Enterprises Group, is one of very few Noongar-owned and operated farms in the region. After years of being leased out, 2018 was the first year of operation in Aboriginal hands.

Selling sheep and trialling bush foods, the farm became the first successful farming business in the group and inspired other Aboriginal land-holding businesses shift their mindset. [14]

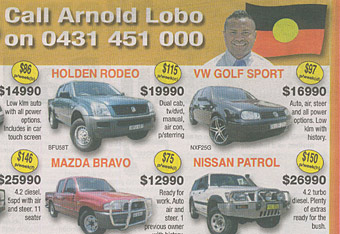

Rare Aboriginal business advertisement

Advertisements for Aboriginal businesses which fly the Aboriginal flag are still a rarity. More and more Aboriginal people are able to get a better education, despite a huge lack of government support in that area.

Adverts like this debunk the myth of the 'lazy Aboriginal' and are testimony to a new class of business people of Aboriginal descent.

Resources

Celebrating Indigenous Governance

The Indigenous Governance Awards celebrate real stories and real case studies from finalists and winners of the Awards, held since 2005 to identify, celebrate and promote effective Aboriginal governance.

Indigenous Community Volunteers

Getting Down to Business is a film shown to raise funds for the Indigenous Communities Volunteers Foundation (ICV). The ICV works in partnership with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people to design and implement community development projects.

If a person fits well into a community and the community accepts them, then whatever the task is will be effective.

— Ron Day, Chairman, Murray Island Council (Torres Strait) [31]