Land

Native title

Learn what native title is and which historic events shaped the modern Aboriginal people's relationship to their traditional lands.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 353

- Number of native title cases in 2018 which determined that native title exists [1]. Same number in April 2010: 84 (116 total cases) [2]; in April 2000: 8 (10 total).

- $120m

- Annual cost of the native title system [3].

- 395

- Number of Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUA) registered [4].

- 6

- Average number of years it takes to finalise a contested native title claim [5].

-

100% - Percentage Aboriginal people owned of Tasmania before invasion.

-

0.06% - Percentage Aboriginal people owned of Tasmania in 2010 [6].

-

0.1% - Percentage Aboriginal people owned of New South Wales in 2010 [7].

-

0.05% - Percentage Aboriginal people owned of Victoria in 2010 [8].

-

50% - Percentage Aboriginal people owned of the Northern Territory land mass in 2015, of the coast line: 85%. [9].

- 2,661,279

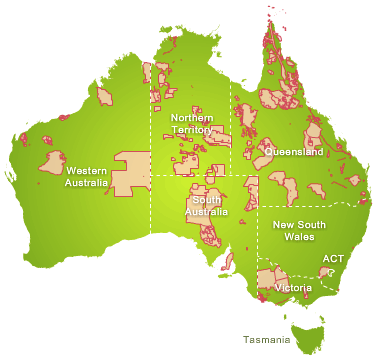

- Square kilometres covered by native title determinations in 2018 [1] (35% of Australia's land mass); in 2010: 854,000 sq km (11%) [10]; in 2005: 7.9%; in 2000: less than 1%.

- 504

- Open applications for native title in 2008 [10].

- 30

- Years it may take to determine native title for the open applications [10].

-

55% - Percentage of land in Western Australia under native title in 2018. [1]

-

23% - Percentage of land in Northern Territory under native title in 2018. [1]

-

28% - Percentage of land in Queensland under native title in 2018. [1]

-

0.6% - Percentage of land in New South Wales under native title in 2018. [1]

-

7% - Percentage of land in Victoria under native title in 2018. [1]

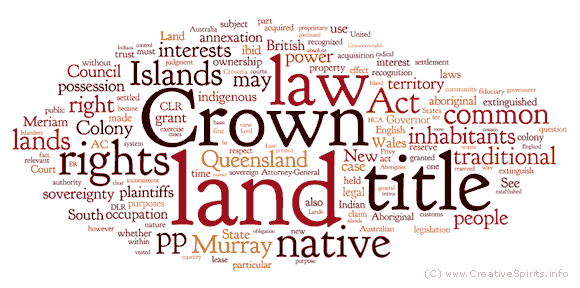

What is 'native title'?

Definition: Native title

Native title legally recognises the traditional communal, group or individual rights and interests to land and waters of Aboriginal people, but viewed from and recognised by, the Australian legal system.

You can think of native title as a bridge between customary Aboriginal laws, which have existed for many thousands of years, and white Australian laws defined and observed by the invading British people.

Native title is tightly linked with a court case the Australian High Court had to deal with in 1982, called the Mabo case. However, note that the Mabo case did not create native title, but recognised it.

Native title and land rights are often used synonymously. But while native title is an entitlement to land, it does not cover the rights to that land. (See comparison of native title and land rights for more detail.)

Native title can be granted in two flavours:

- Exclusive rights include the right to possess and occupy an area without anyone else allowed access. Owners can control who accesses and uses their land. This is only possible for limited areas such as unallocated Crown land.

- Non-exclusive rights means that Aboriginal people have no right to control access and use of the area. Aboriginal people's rights co-exist with other people's rights over the land.

Examples of non-exclusive rights include the right to access, live or camp on the area, to hunt, fish or gather food and bush medicine, to visit and protect sacred sites, and to teach law and custom on country.

The Federal Court of Australia receives and reviews applications, recognises if native title exists or determines how much of it has been extinguished. Extinguishment is final and a big threat to native title, and some governments have unilaterally removed native title for political or economic interests. Compensation is possible but rarely given.

The court can only recognise native title where Aboriginal people were able to prove a continuing connection to the land they claim, for example by maintaining traditional laws and customs (see "evidence" further down). Proving this can be very hard as invasion and colonisation has impacted or destroyed many Aboriginal nations.

In most cases, native title claims are lengthy, complex and expensive.

"Native title puts traditional owners in a stronger position to negotiate agreements, manage their country, and set terms and conditions for access," explains Kimberley Land Council acting chief executive Nolan Hunter. [11] "As a result of native title, governments and industry will be required to sit down at the table with traditional owners to enter into agreements before anything is done on country."

State and territories have the primary responsibility to resolve native title claims. The system is funded by taxpayers' money, and there are no penalties if claims are unsuccessful. [12]

Native Title [is] one of the most complex and slowest parts of the justice system.

— Tom Calma, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner [13]

Native title is not a new or exclusive concept to Australia. The first common law jurisdiction to recognise native title was the United States with the case of Johnson v McIntosh in 1823. [14]

Who is involved in a native title claim?

Applicants for a native title claim are usually groups of Aboriginal people, although individuals can also apply. The claim group are all Aboriginal people who claim to hold native title in a particular area. They authorise representatives (known as the 'Applicant') to make the claim on their behalf.

'Native title holders' are those people whose claim has been determined to exist. They are required to form a corporation (Prescribed Body Corporation, PBC) that acts as their agent or holds the rights and interests in trust.

What sort of evidence do claimants need?

First Nations groups claiming native title need to provide evidence about [15]

- their identity (which might include genealogies),

- their traditional language,

- their connection and responsibilities to Country,

- their social and cultural system (law and custom which is acknowledged and observed),

- their rights and interests in land and water, and

- the relationship between the rights and interests and their law and custom.

Evidence of connection to Country includes First Nations knowledge and cultural material such as art, songs, audio records of oral histories and video recordings of dances and ceremonies.

Can native title take away my backyard?

Many people got a wrong idea of what native title is about and which land can be claimed under it. The media is not innocent about these wrong beliefs being very common. Take the test:

What land can be claimed by Aboriginal people under the Native Title Act?

Local parks?

Beaches that are National Parks?

Vacant government-owned land?

Cattle stations?

Anyone's property if it's on sacred sites?

Backyards, if you don't own your property yet?

Show

Aboriginal people can only claim vacant government-owned land under the Native Title Act and they must prove a continuous relationship with this land.

All other land cannot be claimed because it is already someone's property - see below for conditions that extinguish native title.

Native title cannot be claimed when certain things have been done with the land, such as freehold grants, grants of exclusive possession, residential and other leases and public works like roads and hospitals [16].

When nine parks and reserves in South Australia were handed back to Aboriginal people, Central Land Council Director David Ross assured that "non-Aboriginal people who have previously enjoyed access to these parks have nothing to fear from the handback, but can be pleased that the custodians of these places now have a greater involvement in their care and protection." [17]

Similarly, after a native title claim for densely populated areas of land around Byron Bay, in northern New South Wales, was finally successful, Aboriginal people were quick to affirm that in practical terms the current land use would remain the same. [18]

There is no fear in native title.

— Nat Rotumah, CEO, NTSCORP (Native title service provider for NSW and ACT) [18]

Native title is no threat to non-Indigenous interests.

— Gary Highland, national director Australians for Native Title and Reconciliation (ANTaR) [19]

Key stages in a native title determination process

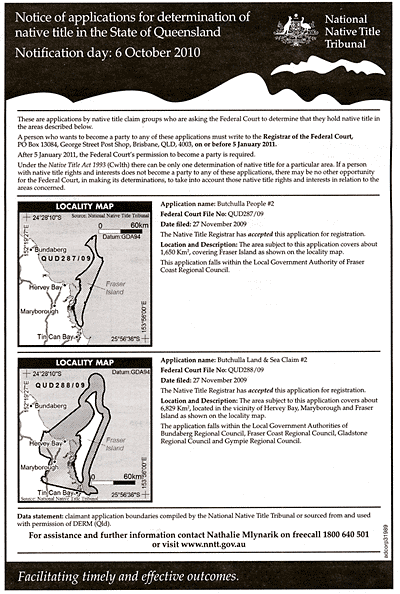

- Submission of the claim. The 'Applicant' files the native title application with the Federal Court of Australia. If the application is in order, the Court sends it to the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT).

- Registration. The NNTT checks if the application is valid for registration. If it is, the claim group gets procedural rights (e.g. rights to be notified and negotiate).

- Notification period. The NNTT publishes the application (e.g. in an Aboriginal newspaper, such as the Koori Mail). It notifies any person or group whose interests may be affected by a successful claim. These persons or groups can become a party to the application.

- Review parties. The Federal Court reviews applications to become a party and decides who the parties to the applications will be. It might also refer an application to mediation.

- Mediation is successful. The agreement reached goes to the Federal Court which decides if native title exists under that agreement (consent determination).

- Mediation unsuccessful. The Federal Court decides if further mediation is needed or if it wants to hear the case.

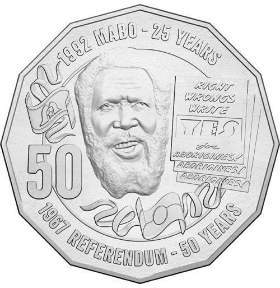

1982–1992: Native title is born: The Mabo case

Up until 1982 it was common belief that Australia has been 'empty' prior to settlement by the English people. The Latin term for an 'empty country' is terra nullius. It would gain special attention in the next 10 years.

The colonial view was that Australia's 'natives' had no connection to the land because the British could not see 'settled' Aboriginal people, houses or farmed land, which were all characteristics of life in England. Most of these misconceptions have now been disproved (see Convincing Ground and Dark Emu by Bruce Pascoe and Gunyah, Goondie + Wurley by Paul Memmott).

The concept of terra nullius also disregarded Britain's own existing laws, which stated that the Aboriginal people did have title rights over their own land. [20]

Eddie Mabo challenges the High Court

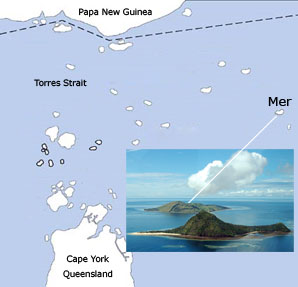

Eddie Koiki Mabo was a member of the Meriam people who are the traditional owners of Mer in far North Queensland. Mer is an island of the Murray group in the Torres Strait.

When Mabo learned that the ancestral land that had been handed down through his family for 15 generations legally didn't belong to him he was stunned. He decided to right this wrong and became a passionate activist for his people's rights.

In May 1982 Eddie Mabo and four other Torres Strait Islanders brought an action against the State of Queensland and the Commonwealth of Australia in the High Court, claiming 'native title' to the Murray Islands and triggering legal proceedings. They claimed that their islands had been continuously inhabited and exclusively possessed by their people who lived in permanent settled communities with their own social and political organisation. [21]

Eddie Mabo claimed that the rights of his people had not been extinguished when the British Crown claimed land title over Australia. He wanted Australia to recognise these rights.

While lawyers processed the case, the Queensland Parliament passed laws (Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985) in an attempt to retrospectively extinguish the claimed rights of the Meriam people to the Murray Islands. [22]

The High Court had to check if this legislation was valid as it would influence Mabo's original case significantly. It found the Act to be invalid as it was in conflict with the Racial Discrimination Act 1975. This case became known as Mabo v. Queensland (No. 1). The decision meant the original case could continue and explains why the most important decision carries the label 'No. 2'.

Now the court could resume its work on the original case which took place on the mainland as well as on Murray Island. And this proved to be crucial as it helped the justices to gain a better understanding of the evidence and of island life.

The High Court's Mabo ruling

The High Court took 10 years to decide. On 3rd June 1992 it ruled in Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) that

- a new doctrine of native title replaced a 17th century doctrine of terra nullius, and that the Meriam people were "entitled as against the whole world to possession, occupation, use and enjoyment of (most of) the lands of the Murray Islands"; [23]

- the Crown had acquired a title to the land of Australia (meaning Australia as a land had been claimed by the Crown to belong to non-Aboriginal people). This title could not be challenged in court;

- the Aboriginal people are still entitled to a claim of their own;

- in certain cases the Aboriginal people's claim could be voided ('extinguished') by events which have happened since the white people arrived and which broke the continued connection of Aboriginal people with their land.

Native title is extinguished through freehold or land leases, but native title continues to exist on Aboriginal reserves, vacant Crown land, stock routes and national parks, but only if the local system of traditional law recognises present owners or managers [21]. If native title was extinguished Aboriginal people have to be compensated.

To remember this important day in Aboriginal history, June 3rd is a bank holiday in the Torres Shire.

Native title is very important to us because it has allowed us to get our country back, to protect our spirits and sites, to go camping, hunting and fishing. Before native title we never had any recognition as traditional owners, we had no rights in our own country. Now we feel empowered.

— Nyaparu Rose, Nyangumarta Elder, Western Australia [24]

Three of the five applicants died before the High Court passed down its ruling, including Eddie Mabo. His legacy lives on in the common name of this ruling, the Mabo case. On June 3, 2007 a sculpture honouring Eddie Mabo was unveiled in Townsville (north Queensland) where Eddie spent most of his adult life. [25]

On May 21, 2008 James Cook University in Townsville named its library the Eddie Koiki Mabo Library. [26] Eddie Mabo had been a gardener at this university from 1967 to 1975 and spent hundreds of hours in the library reading about the histories of indigenous cultures. It was there that he found out in a conversation with professors that his island was legally considered to be Crown land.

In 2001, the collection of Mabo case manuscripts, hosted in the National Library of Australia, was inscribed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.

Mabo win is also a bitter pill

Despite their legal win, the Meriam people have since had less control over their lands than most other Aboriginal communities around Australia.

They had to seek approval of a state departmental head in Brisbane if they wanted to build anything—homes, toilet blocks—because the sub-tropical islands were among the few communities still set aside as "reserve" under trusteeship of the state. [27]

Across Queensland, in most other communities the locally elected councils decide the use of the land.

It wasn't until 2012 that the Queensland government handed the "reserve" title back to the Meriam people, [27] allowing the community to make their own decisions.

But all Aboriginal communities in Queensland still can't own individual blocks of land and buy and sell them like any other Australian.

Further, most successful claims so far have covered unwanted land, land that is extremely remote, small in size, has poor communications infrastructure, a lack of commercial land value, or poor soils. If the land does have mineral extraction potential, it rarely benefits land owners because they lack property rights in these valuable resources.

Read about more problems with native title.

Mabo's legal implications: complex and biased

Michael Anderson, an Aboriginal leader of the Euahlayi tribe in New South Wales, describes the Mabo decision as "legal trickery" because—according to the decision—hunting, gathering, walking on land and ceremonies on country do not constitute a claim to legal title and ownership, whereas erecting fences, buildings and clearing of land does as an act of adverse possession. [28]

"Adverse possession is the means by which the colonisers assert title to alleged 'wild country'," Mr Anderson said. He said this view was underpinned by a 'Doctrine of Discovery' stemming from papal proclamations of the 15th century where Aboriginal people were defined as animals, leaving the world subject to conquer and divide by Christian monarchs.

When the High Court invalidated the concept of 'terra nullius' as a legal justification of the acquisition of sovereignty of Australia, there were only two legal alternatives left how the Crown could have acquired Australia: conquest or cession. [29]

In either case, the Crown would then have been obliged to negotiate with the Aboriginal peoples with regard to compensation for the loss of their lands.

What to do?

The judges decided that ‘native title’ existed in 1788, and therefore must have ‘survived’ in those parts of Australia where freehold title did not exist.

This finding meant that in all the main populated areas of Australia where freehold title of land predominates, the Aboriginal people had been dispossessed, without compensation, and had little or no chance of succeeding in any native title claims. This aspect of the Mabo decision represents the greatest single act of dispossession in Australian history since 1788. [29]

In theory native title may have existed over much of the continent and may have required large compensation payments for its extinction. However, the High Court magically extinguished it, where land has been freeholded, leased or used for some government purpose, by a vote of four to three, at the same time as they recognised its existence, six to one.

— Peter Poynton, writer and historian, cited in [29]

Aboriginal activist Robbie Thorpe says Aboriginal people were being forced to accept native title [30]. "We never wanted that," he says. "We weren't marching down the road demanding native title. We were saying 'land rights'."

The Native Title system is so racist that it has been condemned three times by the United Nations, because it places white interests in land over those of traditional owners.

— Wadjularbinna Nullyarimma, Gungalidda Elder [31]

Who are 'traditional owners'?

The term traditional owners is often used when describing Aboriginal peoples' connection to the land, but also in the native title process.

The roots of the term traditional owner seem to lie in the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976, which established ways for Aboriginal people to claim land in the territory on the basis that they were the "traditional Aboriginal owners" of the land [32]. It is an English language term tied to the Aboriginal decision-making process.

According to the Act the definition of 'traditional Aboriginal owners' is "...a local descent group of Aboriginals who:

- (a) have common spiritual affiliations to a site on the land, being affiliations that place the group under a primary spiritual responsibility for that site and for the land; and

- (b) are entitled by Aboriginal tradition to forage as of right over that land."

Aboriginal people also include law men and women who have an ongoing involvement in any future process or uses of country. They don't need to live on the land to be considered a traditional owner [33].

Note: The term is often used quite arbitrarily. Before you label someone a "traditional owner" make sure that they are okay with that. Some prefer to be called "traditional custodians" instead.

Did you know that the 1992 Mabo decision inspired art and film—most famously the comedy The Castle. It also stirred writers and historians and mustered widespread political activity [34].

1993: Native Title Act: Securing native title rights

After the Mabo decision Aboriginal Land Councils and other Indigenous organisations lobbied the federal government to legislate to protect any native title that had survived 200 years of colonisation.

They also wanted to have a more flexible and appropriate alternative to the courts for claiming and recognising native title. Mining and pastoral industries, however, opposed the Mabo ruling.

In December 1993 the Native Title Act put into law what the High Court's Mabo decision had ruled and made native title claims possible.

The Act

- provides statutory recognition and protection of native title;

- establishes a National Native Title Tribunal;

- sets out processes for the claiming, mediating and determination of native title rights and dealings on native title land;

- establishes processes for reaching agreements for compensation; and

- allows Aboriginal people to gain recognition of rights and interests they have in land and waters according to Aboriginal traditional law and customs.

Under the Act, when a company wants a mining lease on Aboriginal land, the Aboriginal group has 6 months to negotiate with the company. If agreement cannot be reached, either party may refer the matter to arbitration by the National Native Title Tribunal [35]. There are issues with arbitration which is said to be biased towards miners.

At the same time the government, in consultation with Aboriginal people, established the Indigenous Land Council (ILC) which can acquire and grant land for the social and economic benefit of Aboriginal people who could not claim their traditional lands under native title [36]. The Council is funded through the Indigenous Land Fund (ILF). Since 2004 it is self-funding through the ILF.

In the early days after the Native Title Act most cases were dealt with in courts with long trials, but by 2008 the main way to deal with claims was by agreement [37].

It is little understood in the wider community that valid land claims remain the sole form of compensation available to our people in NSW for the dispossession of our lands.

— Bev Manton, Chair, NSW Aboriginal Land Council [38]

Federal Court of Australia

The Federal Court of Australia manages and determines native title. Its powers include to

- refer native title and compensation applications for mediation to the National Native Title Tribunal (see below);

- decide who the people involved in a claim are;

- adjourn proceedings to allow parties to negotiate;

- order overlapping claims to merge into one proceeding.

National Native Title Tribunal

The National Native Title Tribunal was established to assist in the implementation of the Native Title Act. The independent tribunal works with Aboriginal representative bodies, land councils, community organisations, mining companies, local governments, pastoralists and the fishing industry—basically every group concerned with land. It also [39][40]

- registers native title claims, tests registrations and maintains the native title register,

- mediates native title claims under the direction of the Federal Court of Australia,

- assists people in negotiations about proposed developments (future acts), such as mining,

- acts as an arbitrator or umpire when the people involved cannot reach an agreement,

- maintains a register of native title determinations, claims and ILUAs,

- assists people who want to negotiate other sorts of agreements, such as consent determinations of native title and Indigenous Land Use Agreements, and

- conducts reviews and inquiries into native title matters.

Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs)

Indigenous Land Use Agreements deal with practical issues of co-existence between native titleholders and pastoralists or miners. Introduced in 1998, they reflect the parties' aspirations for a positive future as co-users of areas of land or waters.

The ILUA system is a voluntary process designed to resolve native title issues without the need for expensive and time-consuming court cases [42]. Agreements are flexible, can be made before or after determinations of native title, must be registered with the National Native Title Tribunal, and are legally binding.

Each ILUA lays out arrangements for [43][42]

- exploration and mining,

- protection of Aboriginal culture,

- land access and access to pastoral leases,

- protection and use of pastoral infrastructure,

- a mutual understanding of rights and interests,

- the management of national parks and reserves,

- infrastructure development, and

- a consultation process to deal with any future issues.

The first ILUA was registered in 1999 between Adelong Consolidated Gold Mines NL, the NSW Aboriginal Land Council and representatives of the Walgalu and Wiradjuri people in the Tumut and Adelong area of NSW [44]. Just 6 ILUAs were registered by April 2000, 364 ILUAs had been made by mid-2009, and 421 by April 2010. They cover over 14% of Australia's land mass and parts of the sea below the high water mark.

In South Australia, ILUAs are sometimes negotiated and finalised before native title is determined, making the claim process "the beginning of a new and productive relationship" between the parties and the land [45]. Joint management of land covered by an ILUA is about traditional owners and other stakeholders, such as pastoral station owners or the Parks and Wildlife Service, working together to achieve their shared goals and aspirations, exchanging their knowledge and expertise, solving problems and sharing decisions. In doing so they create jobs and training for Aboriginal people, empowering them to more financial independence while they live and work on their country.

An ILUA is a critical step for resources companies gaining finance, as leading global financiers do not fund projects without traditional owner consent. [46]

With an ILUA Aboriginal people do not own their land but are granted "visitation rights only" [47], similar to every other tourist who visits their country.

The ILUA process can fail Aboriginal people. There is not one homogeneous group of 'traditional owners'. There are traditional owners with cultural knowledge, traditional owners with little cultural knowledge and non-traditional owners with little or no cultural knowledge [49]. On some ILUA negotiating committees non-traditional owners determine the fate of Aboriginal land, with non-Aboriginal parties unaware of the differences between the groups.

Further, ILUAs may have only poor outcomes for Aboriginal people. An ILUA over Adjahdura Land on the Yorke Peninsula in South Australia only offered one job for one Aboriginal person for 5 years, involved mainly white and non-traditional owners, and allowed the government to extinguish all traditional owners' native title rights to the land [49].

Once an ILUA is final, state governments can cancel all native title over the area and Aboriginal people cannot reclaim native title rights in the future, regardless of whether or not any planned projects on the land go ahead. [46]

Michael Anderson, leader of the Euahlayi tribe in northern NSW, is concerned that ILUAs don't offer enough protection against development.

"There is the question, what if the governments want to change the purpose of some of these national parks/reserves, or for that matter, make a law that permits mining within these same national parks/reserves?" he asks [48].

"I can assure each and every one, that if you have not put a special clause in your ILUAs to cover this then you lose all your rights to negotiate and/or say no to development and mining. In the long term our children and their children will not appreciate the giving away forever of our and their rights and interest to these lands, airspace and waters."

[Joint management is] about caring for our land and preserving the sacred sites and stories for generations to come.

— Wali Wunungmurra, Chairman, Northern Land Council [50]

It's Time

It’s time for the ILUA, time to talk about the land, Time to tell these whitefellas how we feel, they don’t understand. To say “It’s not about the money, It’s about protecting what belongs for all time, What those fella’s wanna do is nothing but a crime.“ They wanna dig up all the country, and for what, so they get wealth? Mother nature is suffering, can’t they see her pain, her health. And besides this land belongs to us Aborigines, better yet we belong to her. We been this country’s guardians, since The Dreaming and more...

Extract of a poem by Dan Davis.

Indigenous Protected Areas (IPAs)

An Indigenous Protected Area is an area of Aboriginal-owned land or sea where traditional owners have entered into an agreement with the Australian government to promote cultural resource conservation and biodiversity.

Before native title we knew that we owned the country, but nobody else recognised that. As part of the native title process we have developed a good relationship with the pastoralists so that in the future we can both look after the country together.

— Janet Stewart, Nyangumarta Elder, Western Australia [24]

Native Title Representative Bodies (NTRBs)

Native Title Representative Bodies

- conduct native title cases (case studies),

- negotiate commercial agreements and

- try to identify traditional owning groups.

Usually this research is conducted before any native title applications are made.

With the Native Title Act Indigenous people won the right to negotiate, but not veto, developments on native title lands. When native title is granted, claimants are required by law to set up a Prescribed Bodies Corporate (PBC) to manage their native title interests. They receive no direct government funding and many lack the resources to work properly [51].

The Mabo decision and the Native Title Act left unresolved the issues of native title on pastoral leases and native title to the seas.

Becoming a party of a native title claim

The Native Title Act prescribes that companies intending to carry out explorations or mining leases notify the public so that any person can become a native title party. Aboriginal newspapers publish many such notices.

By becoming a "respondent party", people have the opportunity to participate in mediation meetings with the applicants and other parties. These meetings aim to resolve issues and reach agreements that respect everyone's rights and interests [52].

1996: Wik High Court decision

In 1994 the Wik and Wik Way people claimed an area on the west coast of Cape York Peninsula, in far north Queensland. It raised the question of whether Australian law would recognise that native title could co-exist on some types of pastoral leases because governments had been taking action on pastoral leases that did not comply with the Native Title Act.

The High Court's Wik decision in December 1996 established that native title and other interests in land (such as pastoral leases) can co-exist[53]. Previously the Mabo case said that pastoral leases extinguished them.

The finding led to a very significant increase in the area where native title could be claimed. It also dramatically increased the cost and time required to resolve claims [12].

The pastoral and mining industries, afraid that the court might rule against their interests, sparked a 'take your backyard away' advertising campaign which whipped the Australian people into a wholly unjustified hysteria [54]. It formed views which still persist and are a root of racism and prejudice.

Since then many pastoralists have realised that agreement-making is the best way for constructive relationships with traditional owners, and pastoral business needs can co-exist with traditional activities.

1998: Native Title Amendment Act

The September 1998 amendment is also commonly referred to as the '10 Point Plan' and is a response to the 1996 Wik Decision created by the John Howard-led Liberal government. It seriously diminished the value of the legislation.

The National Native Title Tribunal lost some powers to the Federal Court which is now in charge of managing the progress of native title claims from lodgement to finalisation.

Among other changes the Act introduced the registration test for native title applications. It also allows parties to negotiate agreements about action being taken to settle a native title claim [55]. These agreements can be other than native title, for example negotiating directly with the state to settle native title claims, rather than go through the courts. This is an approach the Victorian government announced in June 2009 and called the Native Title Settlement Framework or Traditional Owners Settlement Bill (see below).

Alternative settlements enable those involved to make progress in ways to suit their local needs, and such settlements can be especially valuable where few native title rights will be recognised or where it will be difficult to prove that native title survives [55].

2009: Native Title Amendment Bill

The government passed the Native Title Amendment Bill 2009 on 14 September 2009 which gives the Federal Court of Australia greater powers to resolve native title claims. It can now manage mediation and pull into line "recalcitrant" claim parties [56]. The burden of proof for ongoing connection to the land was left untouched by the Bill.

What is 'Aboriginal freehold' and 'park freehold'?

One of the titles allowed under the Aboriginal Land Rights (NT) Act 1976 is 'park freehold' or park land trusts. Park freehold title means the parks can only ever be used as a national park [17].

At the expiry date of the leases traditional owners and the government will need to negotiate a new lease.

Another form of title allowed under the act is 'Aboriginal freehold' or Aboriginal land trusts, which usually means 'ownership' of the land. It gives the owner the exclusive right to the land for an indefinite period of time.

2010: Traditional Owners Settlement Bill

The Victorian government introduced the Traditional Owners Settlement Bill on 14 September 2010 to offer a "fairer and more flexible way" to resolve native title claims [57].

Under this framework traditional owners can enter into out-of-court consensus-style settlements while withdrawing their native title claims and agreeing not to make future claims. It is hoped that this process speeds up the resolution of native title claims.

The government welcomed the bill to bring "certainty to land managers, industry and developers" and help resolve claims through negotiation rather than lengthy and costly court cases. It would also open to traditional owners economic development opportunities, reconciliation initiatives and participation in land management outcomes [58].

Critics of the Bill, which was backed by traditional owner groups, said that most Aboriginal people had not seen the Bill and most of the land being considered was land that the state had little use for and was infested with rabbits and weeds. The Bill would give certainty to developers but more regulation and insecurity to Aboriginal people [59].

[The Traditional Owners Settlement Bill] represents one of the biggest shake-ups to native title since the Mabo judgement.

— Rob Hulls, Victorian Attorney-General [58]

2016 & 2019: Timber Creek: A historic precedent for compensation

The Ngaliwurru and Nungali people of Timber Creek (600 kms south of Darwin, NT) won native title for most of their land in 2006. But they were asking for compensation for a number of things that governments had done to their lands during the decades before their claim (granting of tenure and construction of public works, for example roads and water tanks on the path of a Dreaming), which extinguished native title and affected their ceremonial and spiritual activities and connection.

In August 2016 the federal court ordered the Northern Territory government to pay $3.3 million in compensation for damage to sacred sites, the economic value of the extinguished rights, interest and the pain and suffering.

It was the first time ever that the compensation scheme of the Native Title Act was applied to the extinguishment or impairment of native title. [60]

The court's decision is considered "one of the most significant rulings about native title since the Mabo decision" and set a significant precedent in such compensation cases. [61]

To no surprise, the Northern Territory and federal governments appealed the decision and the Full Federal Court reduced the compensation to $2.9 million.

Nevertheless, the ruling set a precedent by including $1.3 million forcultural losses (the loss of cultural connection) and recognising spiritual attachment to the land. The remainder is a compensation for economic loss and interest, which, significantly, is a much smaller component than that for the loss of cultural value.

In September 2018 the Hight Court reviewed this decision, sitting in the Northern Territory for the first time in history. It is also the first time that compensation for extinguishment of native title has been fully explored by the highest Western court in Australia.

On 13 March 2019, the High Court ordered the NT government to pay $2.53 million in compensation to the Ngaliwurru and Nungali people, a landmark ruling establishing a significant precedent for future compensation claims. [62]

This important finding means that the spiritual connection of Aboriginal people to their country is paramount in Australian law – as it should be.

— Jak Ah Kit, interim CEO, Northern Land Council [62]

Aboriginal people can only seek compensation for times starting in 1975 because in that year the Australian government introduced the Racial Discrimination Act.

"Only then did governments have to treat the property rights of Aboriginal Australians the same as other Australians," explained James Walkley, a native title lawyer with Chalk and Behrendt.

"Since the first colonisation of Australia, Aboriginal people have been dispossessed of property and culture, [but] only since 1975 has the loss of native title become compensable." [63]

2017: Federal Court McGlade decision

In February 2017 the full bench of the Federal Court ruled that the Native Title Registrar cannot register an Indigenous Land Use Agreement (ILUA) unless it is signed by all registered native title claimants who are "named applicants". That would remain the case even if any of the named applicants died.

The Court made the ruling in relation to a challenge by 4 Noongar people who did not sign an ILUA over a large area of south-west Western Australia. It has become known as "the McGlade decision".

Experts said that the ruling has "potentially far-reaching consequences" not just for future, but also for the validity of existing agreements [64], while a mining and gas lobbyist claimed it would "cast a huge cloud over existing and future mining projects" and could prevent Aboriginal communities from receiving "hundreds of millions of dollars". [65]

Two weeks after the ruling the federal government responded by drafting a Native Title Amendment (Indigenous Land Use Agreements) Bill 2017 which amended the Native Title Act to facilitate execution of native title claims and validate any previous applications where not all named applicants had signed.

The bill was introduced urgently, but critics assume this was because of an application by Indian mining giant Adani for a huge open-cut mine in Queensland (Carmichael coal mine in the Galilee Basin). The Prime Minister had, during a meeting with their CEO, Gautam Adani, promised to "fix" native title in order to pave the way for the mine, disregarding massive protests across Australia.

It became law in June 2017.

The issue needs to be fixed and will be fixed.

— Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull in response to Adani urging him to resolve native title issues delaying their mine [66]

Benefits of native title for Aboriginal people

Although the process of applying for native title is often a long and difficult one (some last many years), there are also benefits for Aboriginal people when their native title is recognised [67].

- Evidence of ownership. It means a lot to Aboriginal people to be able to prove they belong to the land and the land belongs to them.

- Access to traditional land for hunting and cultural purposes such as ceremonies. Without native title such activities would be illegal and let Aboriginal people have a criminal conviction if they do them, which would prevent them from getting government jobs.

- Renew relationships. Native title helps Indigenous groups to renew relationships with each other and strengthen their cultural ties with traditional land.

- Protection. Native title protects the land which will be passed on to future generations along with the traditional laws and customs which govern it.

- Business opportunities. Aboriginal people can establish businesses and create training and employment, giving them economic independence. They will also take a seat at any negotiation table alongside mining companies and pastoralists to have a say in developments on their land.

- Creation of national parks. Many land use agreements reached along with native title establish new national parks where Aboriginal people work as rangers and guides.

To have a job representing your people and looking after your country—who could ask for anything more?

— Nigel Stewart, Bundjalung nation, Byron Bay [67]

- Enhanced self-respect, identity and pride. The strong relationship Aboriginal people have with their land greatly influences their health and well-being.

- Documentation of history. Each native title claim produces many documents related to the history of the claimed area and the people who make it [68]. Every native title claim also documents an important part of Australia's history.

Hunting rights for Aboriginal people are cultural rights, not commercial rights. This means that they don't hunt to make money, rather they are driven by the sustainability of those animals which adds to the sustainability of their culture. Many non-Indigenous people only worry about iconic species being hunted and not the actual cultural practice and the purpose that is attached to that [69].

Case study: Nitmiluk National Park

On 10 September 1989 the Nitmiluk National Park (Katherine Gorge) was handed back to the Jawoyn people of the Northern Territory.

Since then the Jawoyn have developed Nitmiluk Tours, a cultural-based tour operation at the gorge, and accommodation in the park, providing employment and an economic base for the 17 clan groups of the Jawoyn [70].

"Winning back Nitmiluk... provided us with the capacity to have greater control over our land and communities for future generations," says Wes Miller, CEO of the Jawoyn Association. "It gave us credibility and respect in the business world and with governments, and ensured the preservation of Jawoyn culture, land and wildlife in accordance with traditional Jawoyn law and conservation practices."

Sample native title cases

While courts still negotiate some native title claims other cases have been settled.

City of Perth

In September 2006 the High Court granted native title over more than 6,000 km² of Perth city and surrounds.

But in May 2008 the Federal Court upheld an appeal by the federal and West Australian governments, but it did not decide on native title. The ruling meant that the Nyoongar Aboriginal people had to start their case again [71].

Apart from one that I can think of, [the state of WA has] appealed every litigated determination of native title.

— Alison Vivian, Jumbunna Indigenous House of Learning, UTS Sydney [72]

Devils Marbles (Karlu Karlu)

The Devils Marbles, a tourist attraction 100 kms south of Tennant Creek in Australia's Northern Territory, were handed back to traditional owners on 28 October 2008 [73].

The site was handed back 28 years after a native title claim had been lodged. The Ayleparrarntenhe Aboriginal Land Trust now holds the title to Karlu Karlu and immediately signed 99-year leases with the NT government to allow public access to the area.

Traditional Aboriginal owners consider Karlu Karlu as one of their most significant sacred sites [74].

Story: The Attorney's message stick

Years ago, in 1997, the Gunaikurnai Aboriginal people from Victoria filed a native title claim. They gave Attorney-General Rob Hulls a message stick asking him to return it when he had good news for them.

In October 2010 Mr Hulls returned the stick at a determination ceremony, after the Gunaikurnai people had won native title rights to almost a fifth of Victoria's crown land, the first deal signed under the Traditional Owner Settlement Act 2010.

Mr Hulls received a new message stick with three circles on it—one for women, one for men and a bigger circle for family.

He was told to put it on his desk to remind himself of building strong partnerships with the Gunaikurnai people, and looking after future generations [75].

Section 400, South Australia

'Section 400' labels a former nuclear testing site, about 300 kms north-west of Ceduna in South Australia.

The Maralinga Tjarutja people were moved from the area in the early 1950s so the British government could test atomic bombs there, heavily contaminating the land with radioactive substances and hazardous chemicals. [76]

Hundreds of millions of dollars were spent cleaning up the land, and the first area was handed back in 1984, followed by two more in the 1990s.

The last area, Section 400, was "extensively rehabilitated" and handed back to its traditional owners on 17 December 2009, still containing a few 'no-go zones'.

The Bangarra Dance Theatre incorporated the history of the atomic site in one of their works, called 'X300' which was the operation's code name.

Queensland's biggest native title claim

In December 2010 the Federal Court approved Queensland's biggest single native title claim until then [77].

It granted the Waanyi people native title to more than 1.7 million hectares across the north-west of the state, including pastoral leases, camping and water reserves and a large zinc mine.

Story: Native title inspires Bedouin claims

The similarities are striking. Israel's Bedouin people have lived there for centuries yet the Israeli government does not recognise their villages, provide infrastructure, count them in the census or allows them to vote [78].

In 2009 the Bedouin people prepared a landmark native title test case on behalf of a traditional land owner. It was a first of its kind and they asked an Australian expert to help them prepare the case.

Bedouins are semi-nomadic people who have travelled the desert regions of southern Israel since before Ottoman (which was founded in the late 13th century) and British rule (late 19th century).

Native title resources

It's Still In My Heart, This Is My Country tells the story of survival of the Nyoongar Aboriginal people and the struggle to achieve recognition of native title rights over Perth and the south-west of Western Australia. The book won the 2010 Margaret Medcalf award for excellence in research and provides a detailed history of the Nyoongar people.

Mabo - The Native Title Revolution is a website which looks into the details of the Mabo case: www.mabonativetitle.com

You'll find many documents discussing and explaining native title at the National Native Title Tribunal's website www.nntt.gov.au They also offer two DVDs on native title, "15 years of native title" and "Mining and native title".