Law & justice

Mandatory sentencing

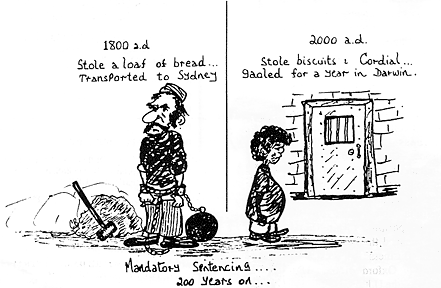

Australia's mandatory sentencing with its exact penalty system has been labelled racist by the UN. After being sentenced youths are likely to be abused or enter a criminal career, and some commit suicide. Only the Northern Territory has abolished mandatory sentencing.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

What is 'mandatory sentencing'?

Mandatory sentencing establishes an exact penalty for each category of offence individually.

Normal sentencing sets a range of penalties, allowing judges and magistrates to interpret the sentence according to the circumstances of the offence and the offender.

Mandatory sentencing laws have taken away the discretion of magistrates to recourse individuals to non-custodial programs and sentences they deem are without risk to society. They must apply the sentence prescribed, it is mandatory.

Western Australian and the Northern Territory both have mandatory sentencing laws. NSW and Queensland have mandatory sentences in some circumstances.

Story: The magistrate who could not be kind

Noongar man Wongi David Jonathon Yarran rode his motorcycle through Perth when police flagged him down to pull over but instead sped past, and in order to evade them drove on the wrong side of the road and ran a red light.

Mr Yarran later said he panicked when he saw the police because he did not have a licence.

In court, Mr Yarran pleaded guilty to evading police and therefore accepted this was an act of driving dangerously. He tearfully expressed that he was remorseful.

Magistrate Felicity Zempilas delivered the mandatory six-month prison sentence. She said that if she could have she would have imposed a lesser sentence but lamented that she was not able to do so.

Australia's mandatory sentencing 'racist' – UN

In 2000 the UN's Committee Against Torture called the mandatory sentencing laws in Australia racist.

According to journalist John Pilger, mandatory sentencing laws have given Aboriginal people "an imprisonment rate at least as high as that of apartheid South Africa, and have been a primary cause of one of the highest suicide rates in the world, among young Aborigines." [1]

In 2008, the committee recommended the abolition of mandatory sentencing due to its "disproportionate and discriminatory impact on the Indigenous population" [2]. It could also contravene the United Nations' Convention on the Rights of the Child [3].

The UN’s committee against torture urged Australia again in 2014 to have its states abolish mandatory sentencing laws, arguing there is mounting proof they affect Indigenous people disproportionately. [4]

In the USA, after decades of minimum mandatory penalties, political parties have started backing away and campaigning to slash mandatory sentences for some crimes, saying the laws are outdated and have led to overcrowding of prisons [5].

The most comprehensive mandatory sentencing laws exist in Western Australia (introduced in 1996) and the Northern Territory (1997). For years they resisted movements to change this legislation.

When we fail to see someone struggling to break the cycle of offending we should assist, not punish further. When families are fighting they need support to resolve the major issues—not charges.

— Brian Steels, Restorative Justice Research Unit, Murdoch University [6]

Video: Mandatory Sentencing

Mandatory sentencing: harsh sentences, youth suicide

Harsh sentences

The community paper that published the cartoon noted: "To remove the right of the judiciary to use their discretion when faced with the case of a repeat offender is to reduce the courts to being vehicles of automatic sentencing... This latest act in a Territory court involving a young offender points to the inanity of mandatory sentencing. Can a crime so minor, even if it is the third such minor crime, be worth a year of incarceration?" [7]

Mandatory sentences for all but the most minor regulatory offences [...] are objectionable because they remove or unreasonably fetter the court's discretion and--inevitably—lead to injustice.

— Nicholas Cowdery QC, retired Chief Prosecutor of NSW [3]

Story: Mandatory jail time for stealing goods worth $23

Just a week after a boy's death, a 22-year-old Aboriginal man from the same community became the third young person to be imprisoned for stealing biscuits and cordial worth $23 from a Gemco storeroom on Christmas Day 1998.

Jamie Wurramara and his friends did not hurt anyone—they simply walked into an open shed and ate biscuits because they were hungry.

Wurramara was sentenced to 12 months' jail because it was his third "property offence". Another youth was jailed for 12 months and another, a second offender, for 90 days.

Story: Youth hangs himself—stole goods worth $90

According to the authorities, 15-year-old orphaned Aboriginal boy "Johnno" Warramarrba was found in his cell on February 9, 2001, hanged by a bed sheet. He had been taken from his remote community in the Northern Territory and imprisoned 800 kilometres away in Darwin for stealing property worth less than $90.

By the official account, he killed himself just five days before he was due to be released from the Don Dale Correctional Centre. An officer had sent him to his room for refusing to wash up, and he was found unconscious five minutes later. Attempts to revive him failed and he died nine hours later at Darwin Hospital.

There are many more cases where under-20-year-olds have been jailed for petty crimes and "damages" of less than 5 Australian dollars.

In the case of Johnno Warrambarrba a public outcry followed, putting mandatory sentencing practices into the national spotlight and pressure on the government to respond.

The focus of these laws seemed to be to protect property rather than people.

A former Chief Prosecutor believes that mandatory sentencing is ineffective because it results in fewer guilty pleas because no discounts can be given for co-operation [3]. Because it increases prison populations costs rise.

Jail for petty crimes still an issue

You might think that today Aboriginal people are no longer jailed for petty crimes. But the following image shows that in 2009 young Aboriginal children were still facing court—and possibly a sentence—for stealing a chocolate bar. Its value: 70 cents.

Mandatory sentencing in the NT and WA

In 2001, when a new Labor government was elected in the Northern Territory, the mandatory sentencing regime ended in October that year. An analysis of the effects of mandatory sentencing concluded that

- Aboriginal people were heavily over-represented,

- the length of the minimum sentence was not an adequate deterrent,

- the effect on prison population was unmanageable,

- the level of custodial sentencing rose by 50% under mandatory sentencing.

Property crime in the Northern Territory actually increased during the mandatory sentencing period and decreased after the abolition of the provisions [3].

Nonetheless, in February 2013 the Northern Territory government passed new mandatory sentencing laws that increased the minimum time offenders spend in prison and restricted judges’ right to suspend sentences for certain crimes, a response to voters' calls "to be tough on crime" [8].

In Western Australia, however, mandatory sentencing remains intact to the present day [9]. In fact, in February 2013 the Western Australian government proposed to expand the state's tough laws, making it legal to detain children as young as 11 years and doubling the minimum jail time [10].

The video that shocked a nation

In July 2016 the ABC's Four Corners programme presented a documentary on child abuse in the Northern Territory's detention centres, specifically Don Dale. The footage showed shocking abuses and violations of national and international laws, and sparked a Royal Commission.

Warning: Strong coarse language and very distressing images. (Documentary approx. 51 min)