People

Mixed race couples

More Aboriginal people enter mixed-race marriages than ever before. They are facing their own set of unique challenges.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

From abuse to romantic interracial relationships

Relationships between Aboriginal people and other races are not a recent trend. The British who invaded Australia were initially almost exclusively male. While some formed genuine relationships with Aboriginal women, most abused and raped them for their sexual gratification.

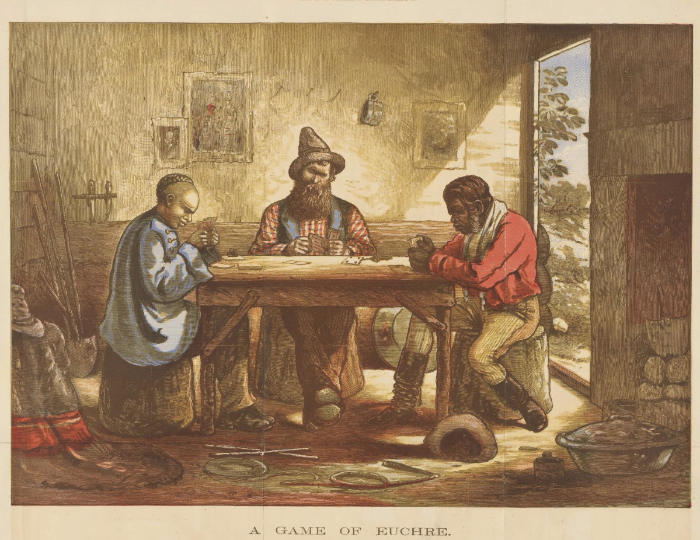

Direct contact between Chinese and Aboriginal people predates invasion, [5] so it is no surprise that the first Chinese migrants who arrived in Australia in 1818 formed relationships with Aboriginal people; a history that is often untold. Chinese men and boys came to Australia in the 1840s to work as shepherds across Victoria, New South Wales and Queensland, [6] for gold in the mid-1800s, and later to build the railroads.

The children of these relationships sometimes call themselves "ABC" (Aboriginal Born Chinese, a variation of the more common Australian Born Chinese). [7]

Both societies were marginalised and considered inferior and in this shared oppression came together and entered intimate relationships. As traditional customs of Aboriginal marriages deteriorated, or potential partners were killed, Aboriginal women (sometimes had to) chose to marry outside their own race, historians say. [6]

Cathy Freeman's heritage is Chinese, English and Aboriginal. Her great-great grandfather moved from China in the late 19th century to work on sugarcane farms in northern Queensland. [8]

I tell people I'm 100 per cent Chinese, 100 per cent Aboriginal, 100 per cent Australian, and most people can't really grapple with that.

— Jason Wing, artist, descended from the Biripi Aboriginal people and the Guangdong province of China [7]

Mixed race relationships on the rise

Aboriginal people are immensely proud of their Aboriginal identity. Surprisingly, more and more Aboriginal people choose non-Aboriginal partners.

The 2006 census found that 52% of Aboriginal men and 55% of Aboriginal women had non-Aboriginal partners, [9] for the first time a majority of Aboriginal relationships. It found Aboriginal "exogamy", or intermarriage, had increased since 2001, and was "well above" the rates of most migrant groups in Australia.

Location was a determining factor of mixed-marriage couples, more significant than education or income. [10] Research found the lowest rates of intermarriage are in regional Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. [1]

In capital cities the proportion was much higher than in rural and remote areas – 82% of men and 83% of women. With more Aboriginal people moving to the cities these rates are likely to increase.

But outside urban areas the rate dropped to 64%. This lower rate was attributed to less opportunities for people in rural and remote areas to mix socially with non-Aboriginal people, but also to significant differences in education and income. Only Aboriginal people who held tertiary qualifications or earned a high income were more likely to intermarry. [10]

Researches concluded that the findings showed Australia's history of cultural division was not inhibiting intermarriage if couples had similar levels of education and earnings. Any remaining divide was due to socio-economic differences and geography.

Aboriginal man Harold Blair met his Anglo-Australian wife Dorothy Eden while studying at the Conservatorium of Music in Melbourne. Their marriage in 1949 caused a public backlash so significant that police had to maintain order at the church. [11]

One of the earliest prominent mixed race couples in Australia was that of Aboriginal boxer Lionel Rose with his wife Jenny whom he married in 1971. A more contemporary couple is Rob Oakeshott, a former politician, who married his Aboriginal wife Sara-Jane in 2004.

When looking at the numbers of Aboriginal mixed couples bear in mind that non-demographic factors have contributed substantially to the rise of people of identify as Aboriginal (i.e. more people than before feel safe to identify as being Aboriginal). It is very likely that many of these newly identifying people increasingly come from mixed couple families. For example, in western New South Wales 94% of children from intermarriages are classified by their parents as Aboriginal, and the national figure is 87%. [1]

Aboriginal gold medal winning athlete and politician Nova Peris was married to three different husbands, Sean Kneebone, Daniel Batman and Scott Appleton, all of whom non-Aboriginal men. "I don't see colour," Peris commented, "I see the man I love". [12]

My Aboriginal grandmother married a white man in 1916. My Aboriginal father married a white girl. I asked him 'wasn't there an Aboriginal girl?' and my dad said 'love has no colour, I loved your mother'.

— Bronwyn Bancroft, Aboriginal artist and illustrator [13]

Finding a partner is more about finding someone with the same set of values than about skin colour.

— David Price, white man, married to an Aboriginal woman [10]

Video: What does it mean being 'mixed race'?

In this short documentary (7 mins) the BBC explores the term 'mixed race' and what it means for residents of the UK.

The term 'mixed race' didn't appear on the UK census until 2001, but it is now the fastest growing ethnic minority there, with the number of mixed race expected to rise to 2.2 million by 2021. But do people of a mixed race heritage identify with the term? Newsnight producer Scarlett Barter, who has a black mother and white father, has been examining her own mixed identity and reveals that it is much more complicated than it may seem.

Characteristics of mixed relationships

Research using 1996 Census data [1] found the following characteristics of mixed couples:

- Wealth. Mixed couples are usually economically better off than Aboriginal-only couples and tend to have higher income levels (which are closer to those of non-Aboriginal families).

- Residence. Mixed families are more concentrated in the largest towns in a region. Only 40% of mixed families rent their accommodation, compared to 70% of Aboriginal and 15% of non-Aboriginal families. The number of mixed couples who are currently purchasing their own home closely matches that of non-Aboriginal families.

- Social and economic status. Mixed families and their house-holds sit between Aboriginal-only and non-Aboriginal families.

- Family size. While Aboriginal families on average count 4.4 persons, mixed families have 3.5 members, and non-Aboriginal families 3.1.

- Family composition. 29% of mixed families are comprised of couples only, compared to 20% of Aboriginal and 44% of non-Aboriginal families.

Mixed couples, mixed challenges

Couples from different races can face a multitude of challenges.

- Cultural history influences the relationship in an unconscious way. The many dark chapters of Aboriginal Australian history surface occasionally and require dialogue and patience, and so do cultural issues specific to one partner only.

- Intergenerational traumas which one partner carries from their family can place a burden on the relationship.

- Racism is just below the surface in Australia and challenges mixed couples in many places.

- Practices one partner observes the other might not. Some members of the Stolen Generations might not want (or be unable) to celebrate their birthday or Australia Day. Among Aboriginal relatives it is common to take advantage of an "open house and open wallet policy". [9]

- Family support is crucial from both families. If they are supportive it helps the couple sustain their relationship.

- Teaching children two cultures to know and respect. This can involve travelling overseas if one partner's heritage comes from a far-away country.

- Respecting the other culture and its ways requires extra effort compared to a partner from your own background.

- Tracing their history as records might have been destroyed (e.g. during China's Cultural Revolution of the 1960s and 1970s [6]).

I hope [my daughter] would bring home an Aboriginal man, or at least another minority, because it is just easier.

— Lee Willis, Aboriginal man, married to an Aboriginal woman [10]

Story: From the kitchen table to a profitable business

Yanyuwa man John Moriarty from Borroloola, Northern Territory, explained his Aboriginal culture to his children by sketching spirit figures and long-necked turtles on the kitchen table. His Tasmanian-born non-Aboriginal wife Ros would create patterns. [14]

What started out to connect their three children to both parents' culture evolved over time into a successful and profitable business, Jumbana Group, most famously known for the Qantas plane painted with an Aboriginal design.

Mixed relationships in poetry and song

Your Own Kind

Stick to 'your own kind' My Dad always said-- Life would be easier If the battles are the same. Those words meant little In our sheltered world, When growing up a Murri And racism was just a word. Educated and assimilated, Pretty and clean. These qualities unnoticed By our Murri boys. Attracting the white girls Because they could. Denying their roots To feed their ego. White boys are nice And treat us just fine. But do not understand Why we still hurt inside. The words of my Dad Will never leave me. But what do we do, Dad When 'your own kind' Don't want you!

Poem by Colleen Johnson, Gooreng Gooreng/Yidinji woman, Bundaberg, Queensland. [15]

The Drover's Boy by Ted Egan

The Drover's Boy is a song by Australian singer-songwriter Ted Egan, published in 1993. It's lyrics recall the time when it was illegal for Caucasians and Aboriginal people to marry, and Aboriginal deaths went unnoticed by the white community.

The song comes from a true story about a Caucasian drover who is forced to pass off his Aboriginal wife as his 'drover's boy'. Ted Egan wrote this song as a tribute to the Aboriginal stockwomen, in the hope that one day their enormous contribution to the Australian pastoral industry might be recognised and honoured. [16]

Excerpt from the lyrics:

They couldn't understand why the drover cried

As they buried the drover's boy.

...

And they couldn't understand why the drover cut

The lock of the dead boy's hair

And put it in the band of his battered old hat

...

And they couldn't make out why the drover and the boy

Always camped so far away

For the tall white man and the slim black boy

Never had much to say

And the boy would be gone at the break of dawn

Tail the horses, carry on

While the drover roused the sleeping men

Daylight – hit the road again

And follow the drover's boy, and follow the drover's boy.

...

So when they build that stockman's hall of fame

And they talk about the droving game

Remember the girl who was bedmate and guide

Rode with the drover side by side

Watched the bullocks, flayed the hide,

Faithful wife but never bride,

Bred his sons for the cattle run

But don't weep for the drover's boy,

Don't mourn for the drover's boy,

But don't forget the drover's boy.

Further resources

Whatever Happened to Interracial Love?

Looking across the ocean, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is a collection of stories by Kathleen Collins, an African-American artist and filmmaker. Humorous, poignant, perceptive, and full of grace, her stories blend the quotidian and the profound in a personal, intimate way, exploring deep, far-reaching issues—race, gender, family, and sexuality—that shape the ordinary moments in our lives.

In "The Uncle," a young girl who idolises her handsome uncle and his beautiful wife makes a haunting discovery about their lives. In "Only Once," a woman reminisces about her charming daredevil of a lover and his ultimate—and final—act of foolishness.

Collins' work seamlessly integrates the African-American experience in her characters' lives, creating rich, devastatingly familiar, full-bodied men, women, and children who transcend the symbolic, penetrating both the reader's head and heart. Both contemporary and timeless, Whatever Happened to Interracial Love? is a major addition to the literary canon.