Politics

A First Nations Voice

Get clarity why a First Nations peoples voice is important and what its key elements are.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Why do we need a Voice?

Australia has a track record of not listening to its First Nations peoples. Governmental shelves are filled with reports and recommendations, but few have been implemented. Since decades, First Nations representatives have urged governments to understand that they know best what can solve the problems First Nations peoples face, and not blanket "solutions" drawn up in ivory towers in Canberra. [1]

What is needed is a secure, permanent structure that advises governments on all things First Nations. A voice which cannot be muted easily.

Securing such a voice in the Constitution is one of the strongest ways to recognise First Nations peoples. Up until now there has been no formal recognition in Australia’s history, but recognition is foundational to a successful reconciliation, a process that started in Australia in the 1990s. Constitutional recognition also prevents governments from further neglecting or ignoring First Nations issues.

In April 2009 Australia signed the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). Its Article 18 stipulates:

Indigenous peoples have the right to participate in decision-making in matters which would affect their rights, through representatives chosen by themselves in accordance with their own procedures, as well as to maintain and develop their own indigenous decision-making institutions.

A Voice implements this "right to participate in decision-making".

We will embark on a new era of unity based on recognition of the three stories of Australia – Indigenous foundations, British institutions and multicultural migration.

— Noel Pearson, First Nations lawyer and academic [2]

Key elements of a Voice to Parliament

The Voice to Parliament is the first key objective of the 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart. Its most important elements are: [1,6.8]

Permanence

In the past, First Nations representative bodies depended heavily on governments to support them financially and, if a government decided so, could be terminated anytime. For example, in 2005 the Howard government suddenly abolished the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission after 15 years of service.

Having a constitutionally enshrined Voice shields such a body from decisions of the government of the day and enables long-term operations and planning.

The constitutional guarantee aims to provide stability and longevity, but requires a change to the Constitution which in turn requires a national referendum. The Uluru Statement is deliberately scarce on how to implement it, as future legislation would set up details, functions, powers and processes.

Independence

Previous bodies were financed by the government which meant it had power over the body's operations. Should it deviate from what a government believed the body should do, the government could threaten to withdraw funding.

The Voice has its own resources to allow it to research, develop and make representations. Independence from governments of any political direction means the Voice can faithfully work towards the needs of First Nations peoples.

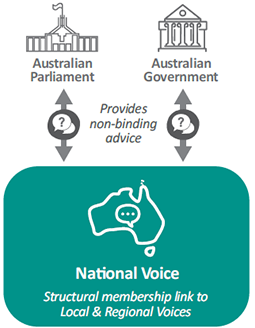

Advisory

The Voice independently advises the Federal Parliament and government about laws and policies that impact the lives of First Nations peoples. It does not have a veto right of the parliament nor could it legally challenge any parliamentary process.

It will be up to the people of the Voice to decide when they provide advice, they would not need to wait for an invitation.

However, parliament and government are not obliged to wait for, or follow, the advice of the Voice and can choose to ignore it.

Obligation to consult

Parliament and executive government (the public service and government ministers) are obliged to consult the Voice early on matters that overwhelmingly relate to First Nations peoples. However, they would not need to wait for representations or advice from the Voice before making laws or decisions.

This stems from past government practice where politicians mostly made laws about First Nations peoples and their lives, but not for them. Such one-size-fits-all solutions hardly worked for the many and diverse First Nations communities, and many such programmes failed as a result, wasting a lot of money.

Community-driven

First Nations communities know best what they need to solve their challenges. Hence the Voice informs itself from the bottom up. Communities elect members (as per the UNDRIP, see earlier) who will be gender-balanced and include young people.

Communities also channel information about what is needed for matters that affect them so the Voice can act on their behalf. This includes issues such as education, health, housing, justice and other areas with a practical impact on First Nations people.

In this regard, the Voice is a true amplification of the voices on the ground.

Details are legislated later

While the principles of the Voice are anchored in the Constitution, the details of the implementation of the Voice are legislated by Parliament in consultation with First Nations peoples and communities.

Such details include the number of representatives, their selection, internal processes, the nature of interactions with Parliament and government and so on.

This means that the Voice can adapt and change with the political environment, and Parliament maintains the authority to legislate the Voice.

No program delivery

The Voice will not deliver any programs (like ATSIC did), do research or manage funds.

Non-exclusive

The Voice won't be a sole representative body but work alongside existing organisations and structures.

Other elements

The Voice will be empowering, community-led, inclusive, respectful and culturally informed. It will be accountable and transparent.

The First Nations Referendum Working Group has worked with the government to assist with timing, the proposed constitutional amendment and question, and the Voice design principles. It delivered its final advice on the constitutional amendment and question on 23 March 2023.

A separate Referendum Engagement Group is working with First Nations people and the broader community to build understanding, awareness and support for the referendum.

Support

Do you support an alteration to the Australian Constitution that establishes a Voice to parliament for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people?

- Yes

- 80%

- No

- 10%

- Don't know

- 10%

Ipsos survey of 300 First Nations peoples in January 2023 [5]

Do you support an alteration to the Constitution that establishes an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice?

- Yes (Sep 2022)

- 53%

- Yes (Jan 2023)

- 47%

- No (Sep 2022)

- 29%

- No (Jan 2023)

- 30%

- Undecided (Sep 2022)

- 19%

- Undecided (Jan 2023)

- 23%

Resolve Politcal Monitor; 3,618 votes; numbers are rounded [6]

Research based on polling by Ipsos among First Nations peoples in January 2023 showed overwhelming support for the Voice. [5] Ipsos found 80 per cent of respondents backed the proposal while 10 per cent opposed it and the remainder were undecided.

The Uluru Dialogue, based at the University of NSW with Professor Megan Davis as co-chair, commissioned research company Ipsos to ask Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders aged 18 and over about the Voice from January 20 to 24. It surveyed 300 people to produce results with a margin of error of 6 percentage points. Asked how sure they were about their view, 57 per cent said they were “very sure” of their support while 21 per cent said they were “fairly sure” and 2 per cent backed the proposal but said they were not really sure about it.

“It’s important that we as Aboriginal people have an opportunity to be able to contribute to policies that impact on us and programs and legislation and that’s the first step,” says Tom Calma, the co-chair of the Indigenous Voice advisory group. [5]

Melbourne University professor Marcia Langton, the other co-chair of the Voice advisory group, says, "Imagine an Australia without these ugly fights about Aboriginal affairs. Why are we the football in politics, far too often with no result? This is why we need the Voice – to take the politics out of good policy design".

Langton also supports the Voice as a path towards improving First Nations peoples' lives. "We know from the evidence that what improves people’s lives is when they get a say," she argues. [7]

Criticism

In the lead-up to the referendum about the First Nations' Voice many speakers expressed their opposition.

First Nations people said that: [8]

- They and their communities are the voice, not a group of people in parliament.

- They have no trust in a Voice to Parliament because it would be "another formal process of government not listening to mob".

- Sovereignty is more important than a Voice.

- A treaty would help put First Nations people straight into parliament rather than an advisory body to it.

- Politicians should address instead issues such as land rights, deaths in custody.

- A voice wouldn't improve First Nations peoples' lives.

When you evaluate their points, bear in mind the following:

- As any other group, First Nations peoples and non-Aboriginal Australians are diverse and so are their views.

- Past history has led to a lot of anger and trauma in First Nations peoples which leads them not to trust government and its bodies.

- Some prefer to see more established demands be implemented instead as they understand them better than the Voice.

- Some politicians oppose the Voice due to political reasons, not because they think it might not work.

- Media make a decision when they publish opinions about the Voice, and there is a high chance of bias towards people who express controversial views or are loud - it means more sales and more clicks.

The referendum

The 2023 referendum, held on 14 October, has two key elements: recognition and securing the Voice.

Australians are asked: [9]

"A Proposed Law: to alter the Constitution to recognise the First Peoples of Australia by establishing an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice. Do you approve this proposed alteration?"

The constitution would also be amended to include a new Chapter 9 titled "Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples". Its details would be:

Constitution, Chapter IX: Recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

In recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the First Peoples of Australia:

- There shall be a body, to be called the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice;

- The Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Executive Government of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples;

- The Parliament shall, subject to this Constitution, have power to make laws with respect to matters relating to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice, including its composition, functions, powers and procedures.

The constitutional amendment has two key goals:

- Establish the key principles of a Voice without going into detail, and

- Recognise First Nations peoples, which has been absent so far.

The referendum is not about a model or details on how to implement a Voice, this is the task of parliament after the referendum. This is because the Constitution is "principles-based", meaning it is not concerned with how you implement the principles it suggests.

Importantly, it recognises First Nations peoples for the first time as the "First Peoples of Australia". So far, the Constitution has been silent on First Nations peoples.

Referendum costs

In addition to the $75.1 million allocated for the referendum in the 2022-23 Budget, the government provided $364.6 million over 3 years from 2022–23 to deliver the referendum. [10] This funding included:

- $336.6 million for the Australian Electoral Commission to deliver the referendum, including $10.6 million for the production of information pamphlets for the ‘yes’ and ‘no’ cases (distributed to all Australian households)

- $12.0 million for the National Indigenous Australians Agency (NIAA) and the Museum of Australian Democracy for neutral public education and awareness activities (launched on 21 May 2023)

- $10.5 million for the Department of Health and Aged Care to increase mental health supports for First Nations people during the period of the referendum

- $5.5 million to the NIAA to maintain existing resourcing levels to support the referendum and continue preparations for post-referendum consultation and delivery.

Canada formally recognised its indigenous peoples in its constitution in 1982, Norway in 1988, Finland in 1995, Bolivia in 2009 and Sweden in 2011.