Self-determination

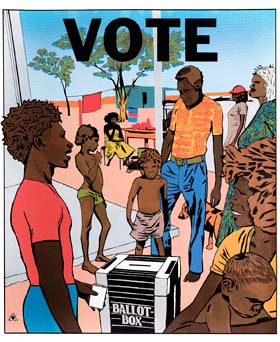

Voting rights for Aboriginal people

Some Aboriginal people were granted voting rights in the 1850s, but it wasn't until 1962 that all Aboriginal Australians were allowed to vote.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Early voting rights

The path towards voting rights began in 1850 with the self-regulation of the Australian colonies and the granting of the vote to all adult male British subjects over 21 in South Australia (1856), Victoria (1857), New South Wales (1858) and Tasmania (1896). This included Aboriginal men.[2]

In 1894 South Australia, which then included the Northern Territory, made laws which allowed all adults to vote, including all women and therefore all Aboriginal women. [3] And in 1895, when South Australia gave women the right to vote and sit in Parliament, Aboriginal women shared the right. Only Queensland and Western Australia barred Aboriginal people from voting. [4]

Very few Aboriginal people knew their rights so very few voted. In the 1890s, Aboriginal men and women voted at Point McLeay, a mission station near the mouth of the Murray River, in South Australian elections and voted for the first Commonwealth Parliament in 1901.

No voting rights for "aboriginal natives"

But voting rights for Aboriginal people were restricted in the first half of the 20th century after Federation and after Australia introduced the 'White Australia' policy. Section 4 of the Commonwealth Franchise Act 1902 specifically excluded any "aboriginal native of Australia, Asia, Africa, or the islands of the Pacific, except New Zealand" from voting unless they were already on the roll before 1901 [5] which were only estimated to be few hundred. [3]

Worse still, electoral officials had the power to decide who was an "aboriginal native" and who was not which led to arbitrary decisions depending if an Aboriginal person lived like a white person or not.

In 1949 the Commonwealth Parliament granted the right to vote in federal elections to Aboriginal people who had completed military service after rising pressure because they had fought side-by-side with non-Aboriginal soldiers. [3]

In 1957 Commonwealth law declared most Aboriginal Western Australians to be wards of the state – that is, in need of government protection. Wards of the state were not permitted to vote. [2]

1962 – Aboriginal people can vote again

In March 1962 the Menzies Liberal and Country Party government finally gave the right to vote to all Aboriginal people. [4] Aboriginal people now could vote in federal elections if they wished, regardless of state law. Western Australia gave them the state vote in the same year, Queensland followed in 1965, the last state to grant that right. With that, all Aboriginal people had full and equal voting rights.

Voting rights they had - but equal? Legislative constraints still made it an offence to encourage Aboriginal people to vote, likely because of the misconception that they might be easier to induce and manipulate than others, a hint towards racial prejudice and assumptions about their intelligence. [2]

In 1971 the Liberal Party nominated Neville Bonner to fill a vacant Queensland seat in the Federal Senate, which he held from 1971 to 1983, being re-elected in 1972, 1974, 1975 and 1980. He was the first Aboriginal man to sit in any Australian Parliament.

It wasn't until 1984 that enrolment and voting were made compulsory for First Nations peoples. [4]

Voting challenges

While by law Aboriginal people have 'full voting rights', in practice much fewer vote than those who do.

Not recognised or able to vote

Many are not recognised by Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) enrolment criteria. If they live in remote communities they may not have a fixed residential address but a main remote community address. Current legislation does not recognise the special circumstances of Aboriginal culture. "Mobile polling" where polling teams visit remote communities could help.

Many Aboriginal voters in remote communities are illiterate and shy about voting so they rely on the candidates handing out How To Vote flyers to assemble their vote. [6]

If people are incarcerated (Aboriginal or not) they are only allowed to vote if their sentence is less than three years.

Not casting a vote

Fewer than 50% of eligible Aboriginal electors are enrolled to vote, [7][8][9] compared to more than 90% of the general population. Of those enrolled, fewer than 50% turned up to vote and those who do vote are 3 times more likely to vote informally than other voters. [7]

Even during elections for the National Congress of Australia's First Peoples—the body aiming to represent the views of Aboriginal people nationally—less than 13.5% of eligible voters cast a vote. [8]

Why is this so?

History is one reason. In the past, most government forms meant trouble or maybe a fine. This fear keeps Aboriginal people from joining the electoral roll.

Another reason is an increasing disengagement from any political process. Witnessing similarly disappointing policies, no matter which party is in power, Aboriginal people don't know who to vote for or who to trust – resulting in "wild swings" to parties over the years. [8]

Not voting can be a political act in itself. If, as in the Northern Territory intervention, the outcome is the same irrespectively of the political party, Aboriginal people are asking themselves: why vote in a system that generates the same outcome?

Seeing so few Aboriginal politicians challenges Aboriginal people having faith in politicians representing their issues.

Informal voting is common – both intentional and due to far higher illiteracy rates, especially in remote Aboriginal communities.

In 2016, the Australian Electoral Commission officially estimated about 58% of Aboriginal Australians were enrolled to vote. But some Aboriginal leaders, non-government and government agencies estimate that only 25 to 30% – or about half – of Aboriginal people who are enrolled actually cast a formal vote. [2]

Tasmanian Aboriginal activist Michael Mansell hasn’t voted for decades because he believes that he is not entitled to vote because he is "not Australian", but a "member of the Aboriginal nation". [10]

I haven't voted in 25 years. Rights to autonomous self-governance as First Nation shouldn't be voted on. Why join the empire? ... Voting is against my lore. My government are my elders.

— Julie Dowling, via Facebook

The Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) has documented the electoral milestones for Aboriginal Australians.

Keepin' It Cool…

A poem celebrating 40 years of Aboriginal voting rights.

Keeping it cool Keeping it strong Can start The lyrics For this song Proud of heritage Real history today Stand up Be counted As history is made The oldest race Australia be proud Dance it Sing it You've got to be loud! Our connection to country Sunrise and sunset From outback To coastline Our seasonal net 40 years of voting It's real and true Marching And sharing Our point of view

Poem by Zelda Quakawoot, Mackay, QLD. [11] Read more Aboriginal poems.