Health

Aboriginal alcohol consumption

Aboriginal people's problems with alcohol began with invasion. Contrary to public perception, fewer Aboriginal people drink alcohol than non-Aboriginal people do. Media portray habits of a few, reinforce stereotypes and ignore efforts by communities to get dry.

Wishing you knew more about Aboriginal culture? Search no more.

Get key foundational knowledge about Aboriginal culture in a fun and engaging way.

This is no ordinary resource: It includes a fictional story, quizzes, crosswords and even a treasure hunt.

Stop feeling bad about not knowing. Make it fun to know better.

Selected statistics

- 1.4

- Number of times Aboriginal people are more likely to abstain from alcohol than non-Aboriginal people [1].

-

29% - Percentage of Aboriginal Australians who did not drink alcohol in the previous 12 months, almost double the rate of non-Indigenous Australians [2].

-

33% - Proportion of Aboriginal people on Palm Island who do not drink. Same figure for non-Aboriginal people: 12% [3].

-

15% - Percentage of Aboriginal Australians who are long-term, risky or high risk drinkers. Same figure for non-Indigenous Australians: 14% [2].

- 60

- Number of Australians who die because of alcohol each week, 1,500 end up in hospital [4].

-

48% - Percentage of Aboriginal mothers who drink while pregnant [5].

- 5

- Rate Aboriginal people die from alcohol-related causes compared to non-Aboriginal people [2].

-

60% - Percentage of Aboriginal Australian drinkers experiencing some alcohol-related harm. Same figure for non-Aboriginal drinkers: 35% [6].

- 1.5

- Number of times Aboriginal people are more likely to drink alcohol at risky levels [1].

-

17% - Percentage of Aboriginal Australians who binge drink. Same figure for non-Indigenous Australians: 8% [2].

-

70% - Percentage of all Australian Australian children who in 2015 blamed adult consumption of alcohol and drugs for the mistreatment of children, compared with 4% of children globally. Australian figure for 2013: 45% [7].

Aboriginal people and alcohol—this combination raises a lot of misconceptions. Nearly everyone in Australia has seen Aboriginal people drinking or drunk in parks, yelling at each other. But is this representative of all Aboriginal people of Australia?

The following short video is an animated infographic that reports on a number of key facts about Aboriginal people's use of alcohol.

There are no words for drugs or alcohol in Dharug language.

— Vicki Thom, Wiradjuri artist [8]

Alcoholic drinks before European invasion

Aboriginal people knew of and used mild alcoholic drinks before the arrival of the invaders. Their use, however, was strictly controlled. They produced alcohol from a variety of plants. Some of these alcoholic drinks were made from:

- Pandanus plant (soaked and pounded cones, eastern Arnhemland)

- Purple orchid tree (Bauhinia) and honey (far eastern Queensland)

- Corkwood (Duboisia myoporoides, Sydney region, water in trunk used), also used as fish poison

- Miena Cider Gum (Eucalyptus gunnii, sap used, Tasmania)

- Bitter Quandong (Santalum murrayanum, presumably from seeds, Murray River region NSW/VIC)

- Fermented honey (southern South Australia)

- Intoxicating roots (Adelaide region, South Australia)

- Coconut palms (just before they flower the flower stalks of the coconut palm exude a sweet syrup – known as tuba – that can be drunk fresh, or left to ferment; Torres Strait) [9]

- Banksia cones (soaked flowering cones, the drink was called 'mangaitch', south-west Western Australia and Perth area) [10]

Interestingly, Aboriginal words for 'alcohol' were often derived from words meaning 'dangerous', 'bad' or 'poisonous', but also 'sweet' or 'delicious' (central Australia) and 'salty', 'bitter' or 'sour'.

Maggie Brady documented some words in her very informative work First Taste:

- poison: kun-bang (Kuninjku language), lungkarri (Wambaya), girrngay (Yidiny)

- salty: ngatjur (Batjamalh), mirripaka (Tiwi), malaa (Kayardild)

- bitter: kutha-karldi (Arabana), kathi-nguku (Paakantyi)

- sweet: pama (Warlpiri), ngkwarle (Kaytetye), wama (Pitjantjatjara)

Use of these kinds of alcohol from natural sources was very limited for another reason: The absence of suitable containers and climatically varying access to these resources prevented large-scale production and consumption of alcohol.

Traditionally, Aboriginal people used plant medicines, healing hands and spirit to recover from and heal trauma, grief, sadness, pain and sorrow [11]. Alcohol has replaced these remedies.

Alcohol consumption after European invasion

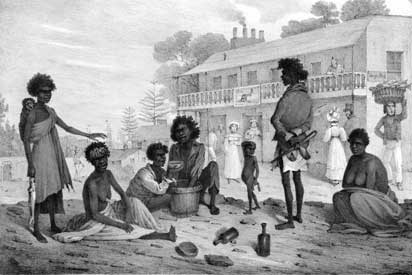

Aboriginal alcohol use changed significantly after white people invaded Australia. Within weeks of the arrival of the First Fleet the first pubs opened and this would shape the way Australian society developed over the next few decades.

Many Aboriginal labourers were paid in alcohol or tobacco (if their wages were not stolen). In the early 1800s a favourite spectator sport of white people in Sydney was to ply Aboriginal men with alcohol and encourage them to fight each other, often to the death.

White settlers also gave alcohol to Aboriginal people to pay for sex. Alcohol-induced prostitution harmed child rearing and accelerated the birth rate of mixed descent children, usually rejected by their European fathers.

Interestingly, Aboriginal people were initially denied alcohol consumption because it was feared that "natives were more adversely affected than others" by alcohol.

Introduction of alcohol

In 1964 a majority of Legislative Council Committee members voted that, for the Northern Territory at that time, alcohol should also be made available to Aboriginal people.

It was, in fact, white people who introduced Aboriginal people to alcohol.

But they didn't teach Aboriginal people about the dangers that go along with alcohol consumption.

"I grew up as a young man when alcohol was introduced to us back in the '60s and we were given the right to drink," remembers Nyoongar Elder, Owen Hansen [12], "but we weren't taught anything about the harm it might do to our minds and bodies and financially as well."

Our people would go to the mines and after work they see the whitefella drink beer. A lot of Yolngu men thought that was the way to be. They thought alcohol made them more powerful.

— Kathy Balngayngu Marika, Bangarra Dance Theatre [13]

Australian drinking culture

Looking at all Australians, alcohol is the most widely abused drug in Australia. It is responsible for [14][15]

- 44% of fire injuries,

- 40% of domestic violence incidents,

- 34% of falls and drownings,

- 30% of road accidents,

- 10% of industrial accidents, and

- 70% of police time tackling alcohol crime.

"Real" Australians engage in alcohol consumption.

— Simone Pettigrew and Ronald Groves [16]

Work hard and drink hard: it's the Aussie way.

— Headline of the Sun Herald [17]

Urban binge drinking 'epidemic' in Australia

80% - Proportion of surveyed Australians who say the nation has a drinking problem. [18]

50% - Proportion of alcohol consumed by 10% of Australia's heaviest drinkers. [19]

20% - Proportion of adults in NSW who admit they can't stop drinking once they started. [20]

- 9.2

- Number of drinks that surveyed Australian men think are safe to drink during one night. [21]

- 5.9

- Number of drinks that surveyed Australian women think are safe. [21]

- 2

- Number of drinks that are in fact safe to drink in one night. [21]

- 6

- Number of drinks more than 1.9 million Australians drink on average per day. [22]

43.3% - Proportion of surveyed 16- to 17-year-old Australians whose "main reason" for drinking is to get drunk. [23] Same figure for all adults in NSW: 36%. [20]

69.6% - Proportion of readers who disagreed that the legal blood alcohol limit for all drivers (not just P-platers) should be 0%. Only 27.5% agreed. [24]

70% - Proportion of surveyed Australian children who blame adult alcohol consumption for the mistreatment of children; same figure for all surveyed children: 4%. [25]

- $1.4b

- Money spent each year for paying for the results of alcohol-fuelled violence. [19]

- $1m

- Money the alcohol industry spends each day on promotion. [19]

You could call alcohol the glue that holds white Australian society together. If you want to "fit in", if you want to be accepted, you should drink alcohol with your friends. Men drink beer, women drink wine, and the drinking rituals they share shape them into a cohesive group.

The omnipresence of alcohol is not helping. ''Every occasion now, whether it's a school activity, a sporting event, getting together with friends or just a barbie [BBQ] in the park, drinking has become normative. In fact, if you don't drink on these occasions, people ask you what's wrong with you,'' says Dan Lubman, director of Turning Point Alcohol and Drug Centre. [26]

Alcohol drives everything from weddings to funerals to sporting events. Almost every social occasion involves alcohol. In stark contrast, most Aboriginal events are alcohol-free.

According to a Centre for Alcohol Policy Research report 95% of people surveyed were unable to correctly identify the Australian guidelines for safe drinking levels. Between 30 and 50% were unable to even provide an estimate. [21]

An analysis from the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare revealed in 2008 that one in five Australians binge-drink once a month or more, [27] in 2011-12 the Australian Bureau of Statistics found that 52% of the population took part in a binge-drinking session in the previous 12 months. [28]

How often do you drink alcohol?

- Couple of times a week

- 36%

- Daily

- 25%

- Weekly

- 12%

- Monthly

- 9%

- Rarely

- 7%

- Less often

- 6%

- Never

- 5%

SMH poll March 2016; 1,461 votes

Almost half of the boys and one third of girls admit that they did "extreme binge drinking" in either adolescence or in their 20s. Of these, more than 40% first started heavy binge drinking when they were teenagers. [29] And of those who did not binge drink as teenagers, 70% do so as adults.

Australia's binge drinking levels are "frightening" and facilitated by easy access, lack of education and exposure to alcohol promotion. [29]

17% of Australia's drinkers consume more than 22 drinks per week and account for 53% of all alcohol sales. [17] 80% of alcohol consumption among 14- to 24-year-olds is done dangerously. [23]

In 2009, as Shadow Minister for Families, Community Services and Indigenous Affairs, Tony Abbott missed a series of key parliamentary votes because he was too drunk and had passed out on a couch. Efforts to rouse him failed. [30]

Police and public health experts say the drinking culture is out of control.

— Sydney Morning Herald [31]

Media usually indulge in portraying unilateral stereotypes of Aboriginal alcohol consumption and the associated problems (see How the media portray Aboriginal alcohol consumption below). They forget that white Australian society shares the same problems. At least half of all assaults in Sydney in 2007 were related to alcohol [33], prompting the City of Sydney to introduce a 2am lock-out for some hot-spots. Still, in 2012, police recorded 6 alcohol-related assaults every day in Sydney [34].

At St Vincent's Hospital in Sydney you can see the "ugly side of Sydney's binge drinking epidemic" [35]. Within 24 hours, the medical team had to attend to 65 people under 30, 90% of whom had to be treated for alcohol-related injuries. Nationwide 4 Australians under 25 die from alcohol-related injuries in an average week [36].

"Alcohol is so imbued in our culture as the thing you do when something good happens, when something bad happens, when anything happens – and when we're bored," says Dr Emma Miller, lecturer at Flinders University College of Medicine and Public Health. [37]

Dealing with alcohol and its effects consumes about 70% of a frontline police officer's time, including dealing with an offender, a victim or witness. Dealing with drunk people is "the most dangerous part of frontline policing" [15].

And it gets worse—78% of surveyed Australians believe that alcohol-related problems will get worse over the next 5 to 10 years [38]. And Australian children know. 45% blamed alcohol and drugs for child abuse in 2013. Two years later that figure exploded to 75%, yet internationally only 4% of children blamed alcohol that way [7].

As a nation, we need to fall out of love with the booze.

— Andrew Scipione, NSW Police Commissioner [15]

Before police casually arrest anyone for drinking, Aboriginal or not, they should ask themselves if it's not them who are giving the wrong example. Within just four weeks between September and October 2011, five police officers were caught drink-driving [39].

More and more young people drink to get deliberately drunk rather than just hanging out with friends [40]. To have a good time, they drink as much as possible and as quickly as possible, often "preloading" with cheap alcohol before heading out.

Interestingly, American youth are far less likely to binge drink or need alcohol to have fun [41]. But there is some hope: this "default position" of alcohol consumption is waning, especially among young people. [37]

What kind of society are we turning into where children under 12 are taken to hospital in an ambulance because of their drinking?

— Mike Daube, director, McCusker Centre for Action on Alcohol and Youth [23]

In Australia, wine is not taxed as alcohol is and subsidised through taxpayer-funded rebates [38].

| These companies... | ...sponsor this event or venue [38] |

|---|---|

| Carlton United Breweries | Australian Football League (AFL) |

| Carlton United Breweries, Campari | National Rugby League (NRL) |

| Chandon | Sydney Opera House |

| Peroni, Belvedere Vodka | Sydney events: open air cinema |

| Bacardi, Smirnoff | Sydney events: music festivals |

Homework: Why do we drink?

Why do non-Aboriginal Australians drink so much? Is it to forget the violent and abhorrent past no-one likes to know, or talk, about? The massacres, rapes, pillages?

Can you find evidence for this theory?

Aboriginal people drink less than white people

Many Australian health surveys have shown that most Aboriginal people are less likely than non-Aboriginal Australians to consume alcohol, a trait they share with indigenous peoples in Canada and New Zealand. [42]

The chart above shows that across all age groups in the low risk group fewer Aboriginal people drink alcohol than non-Indigenous people. On average, 55% of the non-Indigenous people drink at low risk while only 36% Aboriginal people do.

In the risky group more under-24-year-old Aboriginal youth drink than non-Indigenous young people. In other age groups statistically the same number of people drink alcohol. This is also true for the high risk group, except for people over 35 years of age. Here, almost twice as many Indigenous people drink alcohol. The decline in the over-55-year-olds could be attributed to the lower life expectancy of Aboriginal people who on average die before they reach 60 years of age.

According to surveys in 1993 and 1994, the percentage of Indigenous (84%) and non-Indigenous people (82%) who had tried alcohol at some stage in their life was about the same. But 72% of the non-Indigenous population actually drank alcohol, while only 62% of the Indigenous population did.

One common stereotype of Indigenous Australians is that they all drink alcohol to excess. But the reality is that a smaller percentage of Aborigines drink alcohol than do other Australians.

— Mick Dodson & Toni Bauman [43]

I turn away my own siblings if they arrive intoxicated. Some would say this is a rejection of my family. I say it's a strengthening and educating of my family. I will not put my family and our plans and dreams at risk.

— Mary Victor O'Reeri, Billard community, Western Australia [44]

In 2004-05 around half of all Aboriginal adults (49%) reported having consumed alcohol in the week prior to another survey, of whom in turn one third (16%) reported drinking at risky/high risk levels in the long term. After adjusting for age differences, the proportion of Aboriginal adults who reported drinking at risky or high risk levels is similar to that of non-Aboriginal adults.

And less Aboriginal people drink at risky levels. The proportion of Aboriginal people who drank more than two standard drinks a day declined from 32% in 2010 to 20% in 2016. [45]

The alcohol consumption levels are based on a standard drink containing 10 grams of alcohol (equivalent to 12.5 ml of alcohol). The guidelines, modified in 2020 and the same for men and women, stipulate that you should not consume more than 100 grams of alcohol in a week (10 standard drinks), and no more than 4 drinks a day.

Examples of standard drinks include:

- 285 ml glass of beer (a middy/pot/handle)

- 100 ml glass of table wine

- 30 ml of spirits (1 nip)

Anti-drinking video

Broome-based Aboriginal company Goolarri TV created the following video against drinking. It targets all Australians but uses Aboriginal actors.

Aboriginal people who drink do so at harmful levels

While Aboriginal people generally drink less than non-Aboriginal people, those who do are more likely to drink at hazardous levels. Unfortunately, many reports focus on these results rather than the fact that generally they drink less.

Most persons stressed that not all Aboriginals had alcohol problems - many didn't drink at all, or drank only very lightly, but the problem was that many of those who did drink did so very heavily.

— Findings in a 1994 National Drug Strategy Household Survey

The graph shows how many alcoholic drinks people consume. 45% of non-Aboriginal males (the dark blue line) and almost 70% of non-Aboriginal females (light blue line) only consume one to two drinks during a pub visit. The heavier the drinking, the fewer white people engage in it. No female drinker consumes more than 12 drinks.

For Aboriginal drinkers the pattern is reversed. Fewer Aboriginal people drink one to two drinks (10% male, 16% female), the majority are heavy drinkers: More than 40% of the Aboriginal men and more than 20% of the women drink more than 13 drinks when they go drinking.

These figures apply to urban groups, but research has shown that percentages for rural and remote areas are not significantly different [46].

But non-Aboriginal people's drinking behaviour is changing. Australia's largest study into alcohol-related nightlife crime, released in 2012, found that more young Australians are now abstaining from alcohol than in the past, but those who do drink do so in more risky ways [40], aligning their behaviour to that of Aboriginal people.

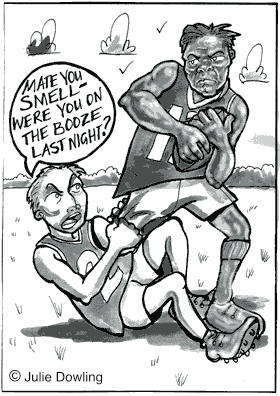

The term binge drinking is often used to describe alcohol consumption by Aboriginal people.

Definition: Binge drinking

Binge drinking occurs when a person consumes alcohol over an extended period intoxicating them and causing them to cease their usual activities and ignore their obligations ('heavy episodic drinking').

It is also commonly known as 'getting smashed' or 'drinking to get drunk'.

Note that the term binge drinking does not relate particularly to Aboriginal people, it is also used to describe drinking habits of non-Indigenous people.

Frequency of drinking

Knowing that Indigenous people drink less than non-Indigenous people, how often do they actually drink?

Fewer Aboriginal people drink daily or at least once a week than non-Indigenous people do. Many more Aboriginal people consume alcohol once a month or even less frequently. This is in stark contrast to the image the media tries to reinforce when reporting about "staggering quantities of alcohol" (Time Magazine, August 2006) being consumed.

Consequences of Aboriginal alcohol consumption

Aboriginal people who (excessively) consume alcohol often face one or more of the following consequences:

- Death due to alcoholic liver cirrhosis or suicide. The average age of death from an alcohol-related cause is about 35 [47].

- Violence, brawls and fights. Women often hesitate to report violent men for fear of yet more deaths in custody.

- Health problems. Alcohol is a major risk factor for health problems such as liver disease, pancreatitis, diabetes and some types of cancer. Many medical conditions cannot be properly treated because of alcohol addiction. Some Aboriginal people never receive any treatment because of this [48].

- Less food security. When drunk, or when yearning for the next drink, alcohol-depended people have less interest in buying food or preparing the next meal.

- Community breakdown. This can also manifest in lack of community support for the drinker.

- Social problems, e.g. low self-esteem, lack of direction.

- Family breakdown. Adults neglect their children as alcohol becomes their main focus.

- Financial problems

- Theft or crime which is much higher for Aboriginal people than for white people.

- Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) or Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD) – see breakout below for more details.

- Accidents and death such as from motor vehicle accidents, falls, burns and suicide.

- Unemployment further exacerbating Aboriginal unemployment.

You know how you destroy a culture? ...You make sure that kids are born with alcohol fetal syndrome, they won't be able to pass on the Dreamtime and the culture.

— Alastair Hope, Western Australia coroner [49]

Love is not enough—Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder (FASD)

Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders is an umbrella term used for a group of incurable but preventable conditions caused by exposure to alcohol before birth. Alcohol damages the developing child and its main target is the brain.

Children with Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) usually have distinctive facial features (e.g. small eye openings, thin upper lip, flat midface). These develop during the first trimester - before many women know they're pregnant. Babies may be low birth weight and brain abnormalities.

Children with FAS cannot learn or memorise well, a devastating effect in Aboriginal communities where culture is passed down orally.

The brain damage causes also problems with thinking, judgement, reasoning, behaviour, language and speech. It is responsible for low IQ, poor growth, motor co-ordination problems, and social and behavioural problems. Sufferers are easily overstimulated, don't socialise well and need routine.

Mature sufferers from FASD are vulnerable to bullying, abuse, assault, breaking the law, substance abuse and inappropriate sexuality.

FAS is an affliction across all cultures and not exclusive to Aboriginal people. FAS rates among Aboriginal people are estimated to be between 2.76 and 4.7 per 1,000 births (general population: 0.06 to 0.68) [50].

Aboriginal women from Fitzroy Crossing asked researchers to quantify the FASD problem affecting their children. This led to Australia's first ever prevalence study of FASD – the Lililwan study, meaning "little children". Because local women were involved in every stage of the research, the participation rate was 95%, nearly unheard of for such a study. [51]

The study found one in four children has some form of permanent damage. Mothers often have no idea they are damaging their unborn children, as FASD wasn't talked about at that time.

At the federal level in Australia, FASD is not recognised as a disability. [51] Across Australia, 47% of pregnant women still drink, [52] but the proportion of Aboriginal women halved from 20% in 2008 to 9.8% in 2014-15. [45]

"They may nod and smile and appear to understand what a parent or teacher is saying but they may have forgotten what they were taught the day before," notes paediatrician James Fitzpatrick. [51]

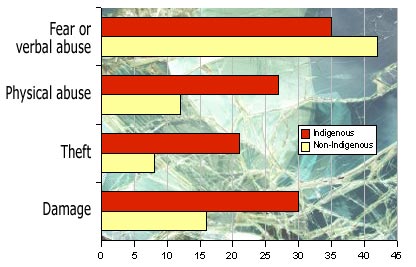

Aboriginal people are more than twice as susceptible to alcohol-induced crime. And the figures could be even higher because a lot of victims don't report an incident because they know the aggressor or don't want to see them prosecuted.

Alcohol problems in Halls Creek

Alcohol and substance abuse is a huge problem for Aboriginal communities in Western Australia. Qatar-based and government-owned 24-hour English-language news and current affairs TV channel Al Jazeera English reports from the isolated town of Halls Creek.

Read 'Do alcohol bans solve the problem?' for positive news about Halls Creek's alcohol ban.

Why Aboriginal people drink

As shown above, Aboriginal peoples are less likely to drink alcohol than other Australians. But those who do drink are more likely to drink at dangerous levels. Why is that so?

Aboriginal people face the same challenges and stresses as everyone else, but some are unique to them due to a history of invasion and colonial violence. Trauma is a major contributor to alcohol abuse.

There are many causes of Aboriginal alcohol abuse:

- Trauma that extends across generations and often manifests as unprocessed anger, pain and rage. This requires healing, but people use alcohol to numb the feelings which follow childhood abuse, racism, violence or bullying. Losing inhibition can be an aim when drinking, giving people an outlet for their poisonous rage in yelling, screaming and violence. [53] "When you drink and you have a really bad hangover, the only thing you need to think about the next day is the hangover," says Stuart Diver, the sole survivor of a fatal landslide in the Snowy Mountains who also used alcohol to self-medicate his trauma. "That’s the cycle some people get into and never get out." [54]

- Breakdown of traditional social controls and family structures.

- Separation of family. Some are unable to recover from the trauma of the Stolen Generations that affects almost every Aboriginal family.

- Lack of group identity. Traditionally, Aboriginal people found identity through ceremonies that fostered community cohesion.

- Lack of traditional rules. Traditional rules for behaviour around alcohol are no longer observed. Prior to invasion strict rules governed consumption of alcohol-like beverages.

- Resistance to imposed controls. Control forced on Aboriginal nations (e.g. the Northern Territory Intervention) is met with resistance.

- Social tension. Alcohol serves as a way to escape tensions and frustrations resulting from poverty, unemployment, discrimination, racism, boredom or dislocation.

- Frustration that their problems are still not solved, their voice is still unheard, self-determination still a work in progress.

I was a sole parent, I felt discrimination in trying to get a house for myself and the children, I had a lot of anger inside and I turned to alcohol.

— Memory of Alex Gater [55]

People have to remember there's a reason why Aboriginal people drink... Drinking is escape. Have a few drinks and you can forget everything.

— Nelson Bieundurry, local resident in Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia [56]

Can alcohol bans help?

In October 2007 the Wangkatjunka community south of Fitzroy Crossing in Western Australia imposed a ban on all alcohol sales except light and mid-strength beer [57]. The ban came about after Aboriginal women lobbied desperately because of a high number of deaths that occurred in Fitzroy. After the initial five-month period the ban was extended for another year.

Another Aboriginal community, Oombulgurri, in the Kimberley in north-east Western Australia, became a dry community in November 2008 after the suicide of five Aboriginal people. The liquor ban came into effect after a Western Australian coroner found that both alcohol and sexual abuse had been factors in the suicides [58].

After a 2-week trial period Halls Creek also introduced an alcohol ban in 2009. A review of the first 12 months found "a dramatic reduction in noise, anti-social behaviour, litter and street drinking" [59] and a "significant" reduction in alcohol-related incidents involving police, alcohol-related injuries and presentations at the hospital and a 70% reduction in the number of people who came to the Halls Creek Sobering Up Centre.

The Kimberley communities of Yakanarra and Bayulu announced grog bans in April 2010 [60].

Alcohol bans seem to produce a mixed bag of advantages and disadvantages.

Benefits of an alcohol ban

- fewer incidents of domestic violence, assaults, injuries, drunkenness and anti-social behaviour,

- "elders are being able to sleep at night" [61],

- families buying food instead of alcohol,

- police callout rates and arrests dropping by about two thirds,

- fewer and less serious hospital admissions (the Queensland community of Woorabinda reported a drop from 11 to one hospital admission per quarter for assault when the community went dry [62], Norseman (WA) reported more than 60% fewer admissions [63], Fitzroy Crossing (also WA) 48% [61]), however, hospital admissions in nearby communities can increase because drinkers move to where alcohol is available;

- fewer suicides; in Fitzroy Crossing suicides before the ban were as high as one per month [56],

- some give up alcohol completely and move back to their homelands outside of towns [56],

- people go out and socialise as they go fishing and hunting,

- school attendance rises, in Fitzroy Crossing by more than 14% [61].

Elders are talking about how well they can sleep at night.

— Joe Ross, community leader of Fitzroy Crossing [57]

In 2008, the Groote Eylandt Liquor Permit Committee won two national awards for their alcohol management initiatives. [64]

- 9,360

- Number of equivalent litres of pure alcohol sold in three months before an alcohol ban in Fitzroy Crossing. [56]

- 2,079

- Number of equivalent litres of pure alcohol sold in three months after the ban. [56]

74% - Percentage by which anti-social behaviour decreased on Groote Eylandt (Northern Territory) after alcohol management initiatives. [64]

68% - Percentage by which property crime decreased.

90% - Drop of numbers of people in protective custody.

Disadvantages of a ban

After 10 years of various types of alcohol restrictions, from completely dry to restricted purchase, mayors from Queensland Aboriginal communities in 2010 concluded that alcohol management plans were not working [65].

Plans fail for various reasons.

- Health services have to deal with people having difficulties to detox.

- Drug use can increase, especially of amphetamines [57][56][65].

- Student school attendance drops significantly [66].

- Violence and fighting increases[66].

- Alcohol addicts embark on grog sprints, driving hundreds of kilometres to buy alcohol, increasing their accident risk [56].

- Non-drinkers do sly-grogging to supply drinkers with alcohol [65].

- Publicans oppose bans. Publicans can be the only source of alcohol for hundreds of kilometres, making "a killing" from selling alcohol [67]. They earn thousands of dollars a week and oppose bans.

- Families lose money because of fines they have to pay when a member violates the ban [65].

- Drinkers simply relocate, for example to the outskirts of town.

- Crime rates rise as people break into properties looking for alcohol.

- Drinkers set up drinking camps outside restricted zones where they binge drink [68].

Juvenile violence has increased in the community [because of the ban].

— Barry Thomson, Queensland Teachers' Union [66]

Alcohol bans seem to be ineffective without considering rehabilitation, mental health support, trauma counselling, suicide prevention and safe houses.

The legacy of alcohol remains in the community even after a ban, like high rates of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS), where the unborn child becomes addicted to and often malformed by alcohol [56].

Surprisingly the number of reported domestic violence incidents and the number of such incidents where alcohol was a factor went up significantly (23% and 20% in Fitzroy Crossing). Aboriginal women seem to be more confident to report such incidents [56].

A carton of full-strength beer brought in by sly-groggers can fetch prices up to $150 [3].

Community-controlled solutions

Rather than ban alcohol outright, communities can create a banned drinkers register, a system of restricting problem drinkers from buying takeaway alcohol or drinking at a pub.

Alternatively, communities can issue drinking permits. Nhulunbuy (far east Arnhemland, NT) and nearby communities, including Yirrkala, have such a permit system which is seen as an example of community-controlled success. [69]

Designed in 2002 by a women’s group in collaboration with 13 local clans, it requires anyone who wants to buy alcohol across the 5 communities to have a permit, with varying restrictions determined by each community’s committee.

Combining both systems means that individuals must have clearance from both the banned drinkers register and the community permit system if they want to buy alcohol.

People can also volunteer to be restricted from alcohol sales. Women in particular are already volunteering to give up their right to buy alcohol to avoid pressure from family to buy it for them. [69]

Story: "I prayed for that schooner"

Kathy Balngayngu Marika is an Aboriginal elder and Bangarra Dance Theatre dancer. She tells how she became dependent on alcohol and how she overcame addiction [70].

"I went through a domestic violence relationship. I had my children through domestic violence and that became something in my head that never went away.

I started drinking and you can't turn your back on it, it's so strong, the smell of it, that craving that tells you drink, drink, come back tomorrow and have another one.

You don't worry about food, just getting money for more drink. I'm not joking. I used to beg for money so I could drink.

I went to the pub one day in 2004, I ordered a schooner [glass] of [Tooheys] New and when I sat down on the table I put it down and I prayed for that schooner, I asked to please take away this smell, the craving and the taste from this beer right now.

And when I took the first sip it turned into a water, like it had no taste at all. I walked out of the pub and I haven't had a drink since."

I don't care who knows

They say it's a crime, drinking beer and wine It's gonna lead a poor man astray. When it comes to grog, I'm a fair dinkum hog I guess I was born that way. I'm gonna drink it and roam til the cows come home If it gives my poor heart ease I don't care who knows, I work for my dough I'll spend it as I please. I was cutting a rug; they threw me in the jug And as the magistrate looked down He said, Youngie Doug, you're a wine-loving mug, You're a menace to this town. I'm gonna put you away; in the cell you will stay Until you learn more sense. I broke down and cried. It was a doggone lie For I wasn't the same he said. I spent a day in jail and they paid my bail And as they opened up the big iron door. I shook my head as I sadly said, I'll never get drunk no more. I made a vow I'll give it up for now And let the blood roll down my vein Until a friend of mine, he had a flagon of wine So we turned it on again. People in town they just run us down And gave us a big bad name Say we drink and fight, but it's quite all right Because the other is doing same But after a while, they're gonna hang their heads For we wasn't such a very bad guy I'm feeling sad and I'm gonna be mad If they hang around my grave and cry. They say it a crime drinking beer and wine It's gonna lead a poor man astray When it come to grog, I'm a fair dinkum hog I guess I was born that way. I'm gonna drink it and roam til the cows come home, If it give my poor heart ease. I don't care who knows, I work for my dough I'll spend it how I please.

This song was written by Aboriginal man Dougie Young for the movie My Survival As An Aboriginal. Read more Aboriginal poems.

Why Aboriginal alcohol management plans fail

In 2008 Queensland media reported that 17 reviewed alcohol management plans (AMP) were failing [68]. In response the state government asked Aboriginal communities to accept more responsibility.

The alcohol management plans, introduced in 2002, fuelled problems such as binge drinking and the setting up of drinking camps on the outskirts of communities outside the restricted zones. Where no police were present, sly-groggers carted their alcohol through the main streets for all to see. Others risked their lives trying to smuggle grog into their towns through crocodile-infested swamps.

Alcoholics cannot be forced to stop drinking, they need to choose it themselves. Imposed measures can increase crime, prostitution, violence and lead to a black market for alcohol [46].

Alcohol has been behind [60 to 70%] of the major assaults, the hospital admissions, the sexual assaults, the domestic violence.

— Lindy Nelson-Carr, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Partnerships Minister, Queensland [71]

A growing body of research suggests that such programmes fail because they do not actively involve Aboriginal communities. The most successful programmes are developed in partnership with Indigenous communities [72].

The community of Umbakumba, for example, is one of the few that are winning the struggle against alcohol abuse because the community owns the programme, women are empowered and government agencies form partnerships with the community. Jobs are another important factor in managing alcohol. Under the Northern Territory government's mandatory alcohol rehabilitation program drinkers who are taken into police custody 3 times in 2 months are locked up for treatment in a 12-week program. But there is no concern for the situation drinkers are in.

A man who participated in the program was back within about 3 weeks, saying, "It's impossible out there. There's no work for us. All my friends drink and alcohol is so readily available everywhere," according to addictive medicine specialist, Dr Lee Nixon [73].

"And he almost exactly paraphrased what the research says. At the outset it was clear that [the NT government was] introducing a program with no evidential base for effectiveness." Dr Nixon left the program in protest.

How alcohol management plans (AMPs) criminalise alcoholics

Under AMPs, some people whose only crime is to suffer from alcoholism have to serve jail terms [72]:

A man had been an alcoholic for several years. He was convicted of violent offences in 1988 but hadn't offended for 15 years thereafter. Then he came back into contact with the criminal justice system only because AMPs were introduced.

In 2004 he was found possessing one (!) can of beer in an alcohol-restricted area. He was sentenced to one month in prison.

The following day he was caught with one cask of wine for which he got six weeks of imprisonment.

While the sentences were overturned on appeal, this is a good example of how quickly Aboriginal people can go to jail, swelling the already high Aboriginal imprisonment rates.

Many of my peers decide to break the law to go to prison to stop drinking and get help.

— Nelson Bieundurry, local resident in Fitzroy Crossing, Western Australia [56]

The Grog Brain Story

"Most mainstream health resources aren't appropriate or readily available to Indigenous people, particularly those living in remote communities," says Dr Sheree Cairney, a research fellow at the Menzies School of Health Research in Darwin [74].

When developing educational materials for Aboriginal people Dr Cairney advises to consider "cultural appropriateness, literacy and linguistic diversity".

One product of her research is the Grog Brain Story, which is part of a broader multimedia campaign to provide Aboriginal people with practical information on the damage alcohol causes to the brain. The story is available in English, Kriol and Warlpiri.

How the media portray Aboriginal alcohol consumption

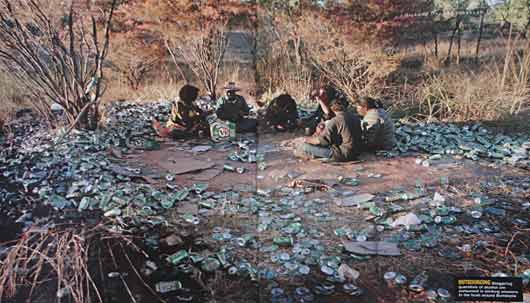

In August 2006 the Australian version of the Time Magazine published the article "The Demon Drink" where it featured a double-page image of a drinking session in the bush around Borroloola, Northern Territory (NT).

The article calls Aboriginal drinking in this remote outback town a "drinking epidemic", claiming that "most Top End towns" share this fate and Borroloola is "just another community in the queue" for support plans from the NT government. The author mentions two examples of serious bodily harm inflicted by drunk Aboriginal people and claims that "such incidents are as common in the Top End as the crunch of green aluminium cans underfoot".

This article was part of the magazine's "Australian Journeys" special which was to "capture the spirit of the longest road in the South Pacific", the Highway No. 1. I strongly dispute that this is the true 'spirit' of this remote community.

In his book Land is Life, published in 1999, Richard Baker tells the story of the Yanyuwa people, most of whom now live in or near Borroloola, located 970 kms south-east of Darwin. Baker finds an altogether different situation:

The Aboriginal drinking problem in town [Borroloola] is highly visible while the large number of people living on 'dry' outstations is invisible. As a result, tourists tend to end up having negative stereotypes of Aboriginal culture reinforced.

— Richard Baker, Land is Life, p.123

Australians judge a whole community on five families who drink.

— Lionel Fogarty, Aboriginal poet [75]

It looks like the reporters of Time Magazine didn't make the effort to visit one of the outstations (or 'homelands') where Aboriginal people control aspects of their life and put up 'no grog allowed' signs on the approach roads. This control over alcohol is denied to them in the town of Borroloola.

It should be stressed how different Borroloola is from nearby 'closed' Aboriginal communities in Arnhem Land. For example, the Yanyuwa would like to control the sale of alcohol to Aboriginal people in Borroloola but are unable to do so.

— Richard Baker, Land is Life, p.119

ConnorCarson.jpg)

One theory claims that the conspicuous litter of beer cans and wine cartons is an expression of resistance towards white management of Aboriginal lives.

If we consider just the statistics for the remote and sparsely populated Northern Territory, around 25% of Indigenous people consume alcohol which is lower than the figure for all of Australia.

Strategies Aboriginal people use to avoid alcohol abuse are

- the declaration of 'dry zones' within Indigenous communities,

- prohibition and restriction in shops and supermarkets,

- community policing and licensing,

- replacing alcohol with Kava, an alternative drink from the Pacific Islands, used particularly in the Northern Territory where it was introduced into Arnhem Land during the 1980s. Made from the crushed root of a pepper plant mixed with water, Kava can cause several damaging health conditions [76].

It has to be kept in mind, however, that such projects are in danger of failing until the causes of excessive drinking are removed.

Help for Aboriginal people who want to stay sober

Indigenous Sobriety Group

The Indigenous Sobriety Group is is a non-for-profit organisation dedicated to the sobriety and healing of Aboriginal people. It provides support to deal with grief, loss, trauma and abusive lives.

Alcoholics Anonymous (AA)

Alcoholics Anonymous: www.aa.org.au.

Further resources

The book Under the Influence is a unique look at Australian history as seen through the perspective of the influence of alcohol. This well-researched book shows how the patterns for alcohol use (and abuse) can be traced back to the very early days of white settlement.

It takes you all the way up to the present day and our ongoing concerns about teenage drinking and alcohol-fuelled violence, as well as the role of industry players in the promotion and packaging of an increasingly dizzying array of alcoholic products.